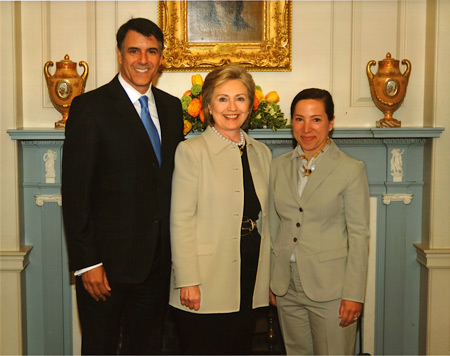

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton with Markos and Eleni Tsakopoulos-Kounalakis

By Markos Kounalakis

BUDAPEST, Hungary — Many of my Saturdays used to start out with a saunter down Fillmore Street for an early morning cup of coffee while the rest of my family was still in bed.

Budapest is also a coffeehouse city, but more famed for the conversations and art that grew out of that culture than the coffee in the cups.

It has been three years since we left San Francisco and moved to a country that only a generation ago was behind the Iron Curtain. As I look outside my office here, I see the Statue of Liberty — not the one in New York harbor, but the one atop Gellert Hill in Budapest, erected by the Soviets after World War II. From her office window, my wife looks toward a Soviet monument in the middle of Szabadsag ter — Freedom Square — a golden star topping the prominent stone memorial.

From our apartment in Pacific Heights, we looked out on the bay, the sailboats and the container ships crossing under the Golden Gate Bridge. President Obama marveled at the view during the couple of times he visited our home before assuming office. He later appointed my wife Eleni Tsakopoulos-Kounalakis as the U.S. Ambassador to the Republic of Hungary — a complex and demanding job that brought our family to beautiful Budapest.

The Kounalakises in their apartment on Steiner Street in San Francisco.

Early on in our tenure here, we went through a Hungarian national election and a change in government, a revised constitution and a six-month European Union presidency. We’ve had many official visitors from President Obama’s Cabinet, topped by two memorable working visits: one from Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the other from our own congresswoman, former Speaker of the House of Representatives and now minority leader Nancy Pelosi.

High-level working visits are a normal part of embassy life and during last year’s opening of the Lantos Institute, Congressman Tom Lantos’s extended family all came to celebrate in Hungary. The Lantos Institute inauguration coincided with the unveiling by the Hungarian government of a large statue of former President Ronald Reagan.

Reagan is looked on with great admiration by the Central Europeans for his role in confronting the Soviet Union. His legacy — along with that of Pope John Paul II and Mikhail Gorbachev — is considered instrumental in ending the Cold War.

Our upstairs neighbor back in San Francisco, avid Democratic supporter Susie Tompkins Buell, was visiting when the new Reagan statue was unveiled — an event also attended by those on the other end of the political spectrum, including former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, former Attorney General Ed Meese and former Cailfornia Governor Pete Wilson. We kept a close eye on our neighbor, but everyone peacefully broke bread together in the ornate halls of the Parliament building.

I was regularly in Hungary from 1989 to 1991 covering the fall of communism in the region for Newsweek magazine, then moved to the Soviet Union in 1991 and stayed there for a year. I quickly learned to join any queue I spotted. In a place where goods were scarce, a queue was usually a good sign there was something to be had at the front of it. Unfortunately, the habit has not died; I still find myself slowing down to jump into any queue in Hungary, no matter how long.

Everywhere there are signs of the communist past, from the massive apartment blocks to the unexploded bomb uncovered in front of the U.S. Embassy left over from World War II. Sometimes we find ourselves in Monument Park, where only Stalin’s boots remain on a pedestal that once held a mighty statue. Even the types of movies we watch are not likely to be found at the Clay Theater. Our kids watch training films produced by the Hungarian secret police in the 1960s — black and white footage teaching citizens and agents how to spy on each other.

Markos Kounalakis in Budapest on his Ducati motorcycle.

While our time here is fascinating and the work demanding, at every turn I am reminded that San Francisco is far away, and we still have moments of longing for home.

Our kids’ names are on the children’s playground tiles at Alta Plaza Park; Calvary Presbyterian Church is where their scout troops meet; and film director Christopher Columbus’s house on Jackson Street is a place they approached with trepidation during their Halloween trick-or-treating.

The Mayflower Market at Fillmore and Jackson was a local touchstone for us. Three brothers from Greece run the market and we would regularly go down to the store so our kids could chat in Greek with our local grocers, who were always looking out for our guys as they grew up.

I used to ride my Ducati motorcycle all year in San Francisco, a great way to get around town without ever worrying about parking. I had it shipped over to Hungary, but now it stays in a garage about half the year, since the winters are a lot colder than at home.

The neighborhood around upper Fillmore Street is a glorious and privileged one. We have been able to live in Pacific Heights because of the opportunities America and California made possible for me and my immigrant family. This type of social mobility and educational opportunity is available in few places in the world and nowhere more than in our country. You see this to a greater degree when you live overseas.

During our tour of service in Europe, we have experienced a change of views, but we have not lost sight of our love for our friends and neighbors and our life back home.

Filed under: Civics, First Person, Locals, Politics