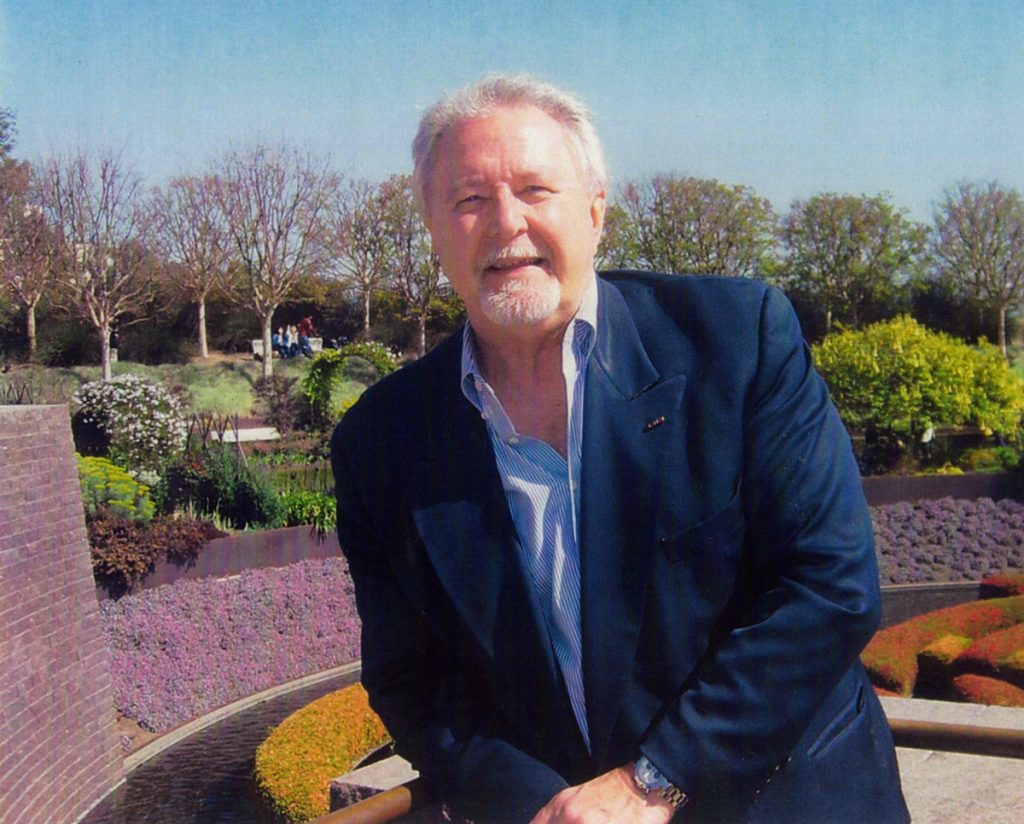

LOCALS | THOMAS REYNOLDS

For 25 years, Jerry Mapp raised money and cultivated donors to help build California Pacific Medical Center into the respected hospital it has become, with a state-of-the-art new home rising at Van Ness and Geary.

As president and chief executive of the CPMC Foundation, Mapp led a team that raised more than $300 million and helped build a portfolio of assets and endowments.

Then he got Parkinson’s disease.

Mapp retired in 2009, but has remained a regular presence in the neighborhood, often having lunch at the Grove, or his favored gnocchi for dinner at Via Veneto.

“It’s my ’hood,” he says, even though he lives out near the ocean.

The foundation now occupies the historic red brick building that once housed an early telephone exchange at Pine and Steiner Streets, which Mapp’s fund-raising helped restore. He remains president emeritus, and he’s still on the job, if not on the clock.

“I still go in almost every day,” he says. While Parkinson’s has taken its toll, Mapp has not had the major motor troubles many Parkinson’s patients experience.

His main problem has been the diminished strength of his voice — his secret weapon in wooing donors. He was always a bit of a showman, acting in dramas and musicals during his college years and singing with the university stage band.

As a fund-raiser, he could always produce flowers or gifts at just the right moment, and show up bedside when friends of the hospital ended up there. He paid close personal attention to the hospital’s major benefactors, including philanthropist Nancy Hamon, for one, who for many years divided her time between San Francisco and Texas. Mapp would sometimes pick her up at the airport and squire her around town. When she expressed surprise one day that he was driving her to pick up her laundry, he replied smoothly: “I love taking you to the cleaners.”

In his own early life growing up in Texas, Mapp was on his way to becoming a Church of Christ preacher. But he eventually realized that was not his calling.

“I was doing it for my mother,” he says now. “She wanted me to be a minister.”

Three months after he left his religious studies, he was drafted. His preacherly past came in handy, landing him in chaplain school. By January 1970 he was in Vietnam, serving an 18-month tour as an assistant army chaplain.

Vietnam cast a long shadow for Mapp, as for so many others. But it hadn’t occurred to him it might be connected to his Parkinson’s disease until one afternoon in 2010 when he was at a car wash in Sunnyvale. He struck up a conversation with another vet, who told him about a new report from the Veterans Administration linking some kinds of Parkinson’s to the Agent Orange defoliant widely used during the war.

“Go see my friend at the V.A.,” the other vet told Mapp. He did, and eventually he got the medical and pharmacy benefits that have helped him battle the disease.

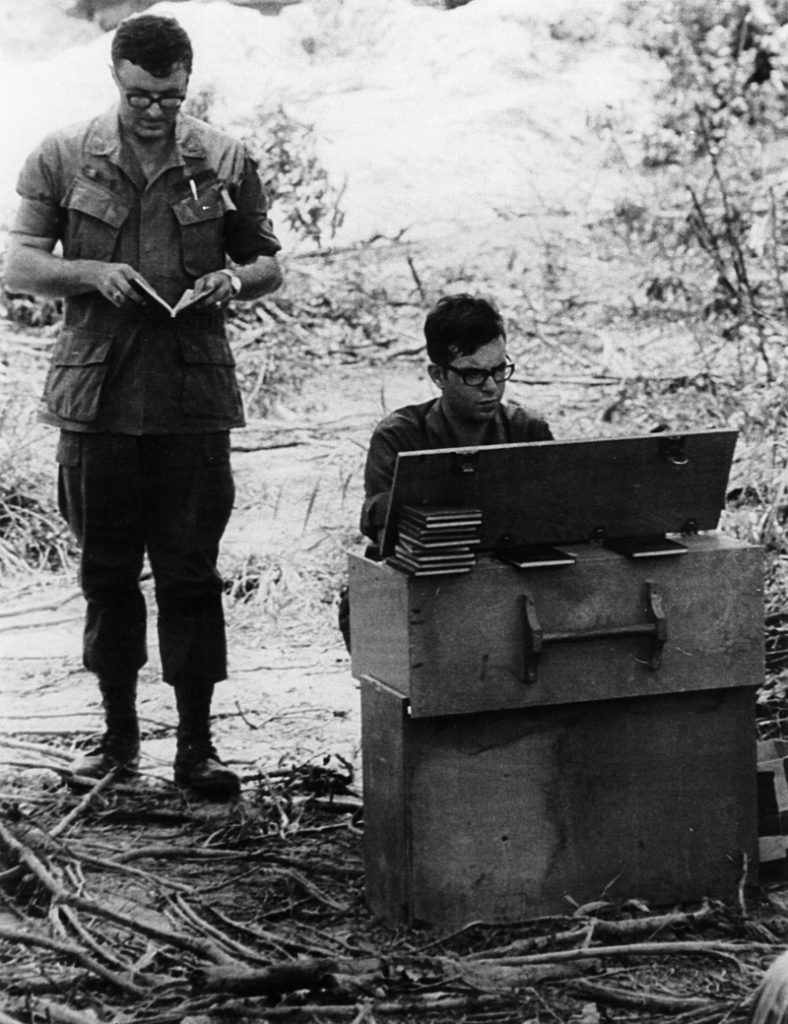

As an army chaplain in Vietnam, a young Jerry Mapp (left) led services in the field — often in clearings that had been defoliated by Agent Orange. Later he would learn that Agent Orange was a likely cause of his Parkinson’s disease.

He went for speech therapy, but found it boring, and knew he needed a more engaging approach.

“Then it occurred to me,” he says. “Maybe I could sing.”

One day he was coming out onto Bush Street after lunch at Out the Door, and saw a woman standing in the doorway of the nearby Unity Church with a songbook in her hands.

“I stopped,” Mapp remembers, “and said, ‘Excuse me, do you know anyone who teaches voice?’ She said, ‘I teach voice.’ ”

And so he began taking singing lessons with Unity’s choir director, Danielle Kane, on Thursday afternoons at the church.

“It’s worked,” he says. “My voice has improved dramatically.”

As added encouragement, he decided he’d throw himself a 70th birthday party in September — and provide the musical entertainment himself.

“It’s my party,” he says, “and I’ll sing if I want to.”

He’s been practicing with noted pianist Billy Philadelphia and recruited the rest of his band in the neighborhood.

“One night I stopped by the Elite Cafe on my way home,” Mapp says. He met Jeff Magidson, who plays guitar and harmonica at the Elite on Tuesdays. Magidson recruited friends to play bass and drums.

“Then one day I was picking up my mail,” he says, and talking to Kevin Wolohan, an owner of Jet Mail. “Kevin told me I needed a horn player, and introduced me to Waldo Carter,” a neighborhood resident who played with Wolohan’s father’s band and many others, including Duke Ellington and Harry James.

The set list for the party includes songs from an album by Willie Nelson and Leon Russell, including “Heartbreak Hotel” and “I Saw the Light.” He started with jazz standards and show tunes, but as his singing lessons have progressed, he’s come home to Texas.

“I don’t want to live in Texas,” he says, “but I like the music.”

Now that his concert date is approaching, he admits, “I’m getting nervous. My teacher told me the other day: ‘I’ve got bad news for you — Willie and Leon won’t be here.’ ”

But it’s friends he’s inviting to the party and performance, and he knows they’ll be kind.

“I stumbled onto this, and it’s a miracle,” he says. “This party is my therapy.”