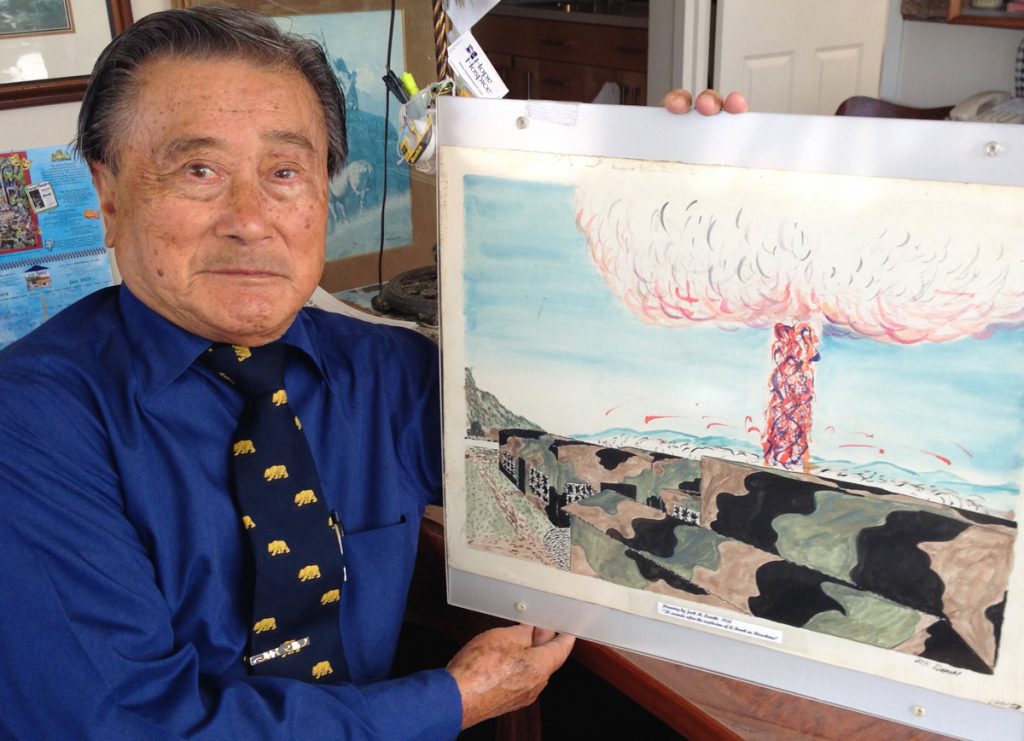

FIRST PERSON | JACK M. DAIRIKI

In Hiroshima City’s Atomic Peace Park, there is a poem carved into a rock that states: “Please rest in peace, for this error shall never be repeated.” It is a pledge to all living people of the world to protect all of humanity.

I witnessed the holocaust three and a half miles from the atomic bomb detonation point.

I traveled to Hiroshima, Japan, in August 1941 with my father on a summer vacation to visit my ailing grandfather. Unfortunately, we were stranded there in September of that year. Finding no passage to return to Sacramento, my father and I were separated from my mother and four siblings, who were interned in the camps at Tule Lake, California; Jerome and Rowher, Arkansas; and, finally, Amache, Colorado.

My classmates and I were conscripted to work for the Japanese war effort at Toyo Factory. I was a 14-year-old student. We worked there from January 1945 until the atomic bomb was dropped on August 6. On that fateful day, because of air bombing raids, my commuter train to the Toyo Factory was delayed by 15 minutes. That delay saved me and my classmates from being in Hiroshima City. We were taking roll call at 08:15 when the bomb was detonated.

We noticed three B-29 bombers traveling toward Hiroshima. It was shortly after that sighting that we experienced the horrific explosion of the first atomic bomb. First, there was a blinding flash and a horrific blast of wind that took out 99 percent of the Toyo Factory windows. I felt my body being lifted by this wind. When I opened my eyes, I was in the midst of dust and smoke and could not see my hands. Then I heard a fellow student run toward the bomb shelter a few hundred yards away; the entrance was at a higher elevation. Perhaps 30 seconds had elapsed. I looked back at Hiroshima and saw the monstrous fire column rising thousands of feet into the air. The whole city was on fire, covered in smoke and fire with no buildings to be seen.

An hour later we peeked out from the cave shelter and witnessed the first victim: a young woman walking with her arms extended, her ragged clothes hanging from her arms and her hair burned off. She was looking straight ahead and walked like a ghost. We noticed as she came closer that it was not burned clothes, but her skin, hanging from her arms.

We were instructed to return home if we were able to walk. I boarded a ghost train with the paint burned off and windows shattered. Inside the train were many injured people asking for medical aid. I could not help them, so I dismounted the train to walk home, a distance of 10 miles. My grandmother welcomed me — she was scanning the horizon for my return. The house was not damaged, except that all the sliding doors were down but unbroken.

There were 55 hospitals, 200 doctors and 2,000 nurses in Hiroshima City before the bombing. What remained were three hospitals, 20 doctors and 170 nurses to help the wounded. There were 80,000 people who died near me in the city.

I can never forget the image nor the smell of death.

Filed under: First Person, Neighborhood History