ARCHITECTURE | THERESE POLETTI

In the spring, neighbors and patrons of the Elite Cafe were dismayed to hear that the 35-year-old restaurant had been sold, fearful it would fall victim to the current depressing trend in San Francisco of gutting historic interiors down to the studs.

But news that the buyer was a group headed by San Francisco restaurateur Andy Chun, who was responsible for a sensitive 2014 remodel of the historic German beer hall Schroeder’s in the Financial District, reassured patrons who cherished the Elite’s Art Deco interior. Chun said his plans were to keep much of the Art Deco interior intact, but with a contemporary interpretation of the decorative style popular in the 1920s and 1930s.

The Elite, like Schroeder’s, is among a handful of historic restaurant interiors left in the city. While the Elite Cafe has been at 2049 Fillmore Street since 1981, its Art Deco home was originally commissioned as a restaurant for John G. Kisich, owner of the Lincoln Grill, which was then located across the street at 2052 Fillmore. Building permits indicating an estimated cost of $5,000 were filed in September 1932 and the building, designed in what was then called the “modernistic” style, first appears in city directories in 1934 as home to the Lincoln Grill.

The one-story plus basement building was designed by architects Irvine & Ebbets. In its era, the firm was responsible for many beautifully executed apartment buildings in San Francisco. Many were done in the Art Deco style, including a four-story apartment building at Scott and Beach Streets in the Marina, replete with fantastic details such as Egyptian figures and peacock imagery.

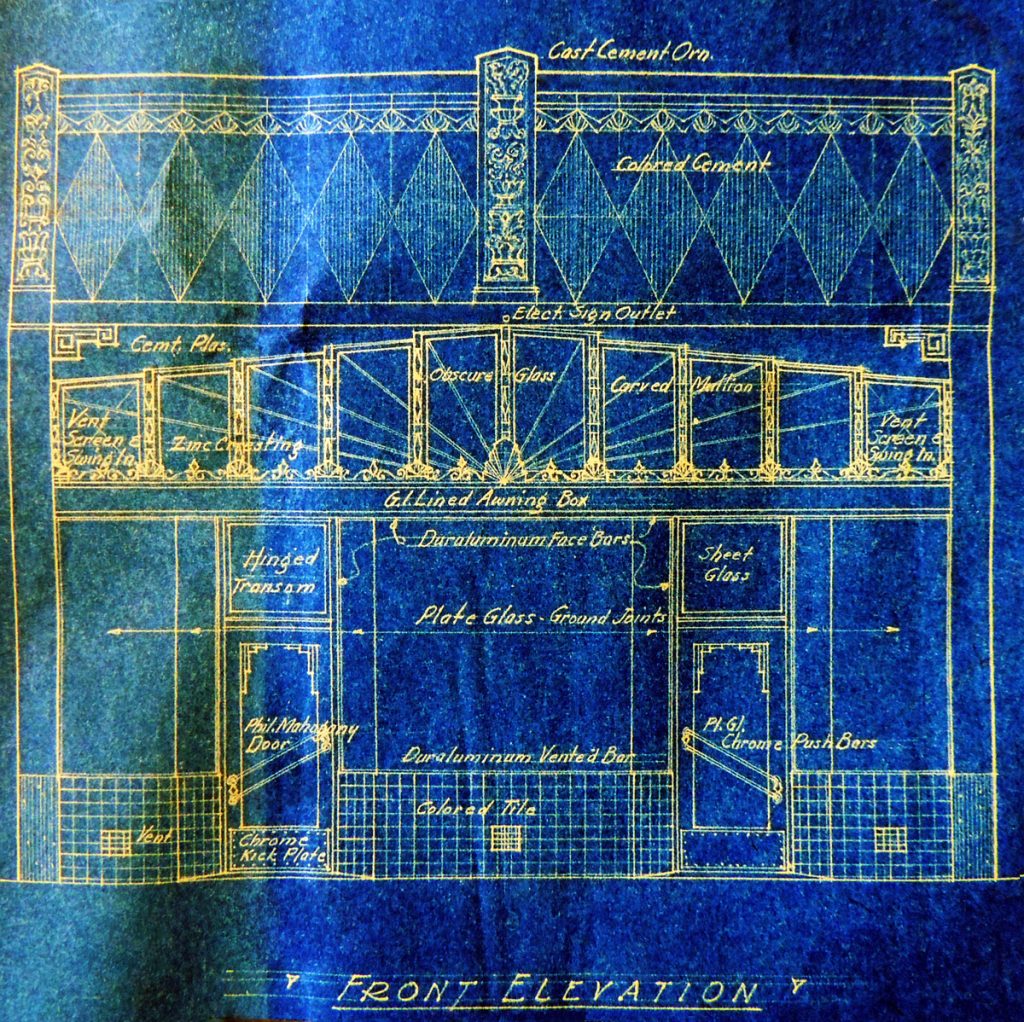

For the Lincoln Grill, according to the original blueprints, Irvine & Ebbets deployed touches seen in their other buildings, including the use of colorful tiles. Black and yellow tiles form a zigzag above the transom windows and a wainscoting along the facade of the restaurant. A raised zigzag cornice detailed in cement accentuates the top of the building, with a large repeated diamond pattern etched in cement below. A stepped design common in the period frames the top of the Philippine mahogany front doors and the main plate glass window.

Today these exterior details, along with a neon sign reconfigured for the Elite Cafe in the 1980s, are largely intact. But in the new remodel, the zigzag and the diamond pattern in the facade have been obscured by black paint.

Inside, the travesty of new paint continues. When patrons walked into the old Elite, they felt the warmth of the woodwork that was everywhere: the beautiful detailed bar, the semi-private booths, the chrome-detailed doors, the paneling and dividers in the front and back of the dining room.

In the remodel, designed by BCV Architects of San Francisco and New York, nearly every available wooden surface has been painted over in a color palette that might be called “A Couple of Shades of Gray” — a dark bluish slate (Benjamin Moore’s Polo Blue) for the booths, bar and woodwork and a charcoal called Englewood Cliffs on the walls. Chris von Eckartsberg, principal architect at BCV, says that the booths, in fact, had already been painted at some point and were in need of a complete refinishing.

“The design and ownership team decided that we would be able to maintain the soul and the classic quality of the Elite Cafe while breathing new life into it by changing the color palette to a more luxurious collection of hues,” he says.

The moldings at the top of the high ceiling are highlighted in white, an echo of the redone retro-inspired white and black hexagon tile floor. The floor is probably the best improvement made, as it harkens back to the original magnesite floor specified in the original plans. The architects said they matched the floor to the threshold and to old photos of the Lincoln Grill.

Too bad such care was not taken with new light fixtures. Most of the Art Deco fixtures that had persisted or been added through many remodelings have been ripped out. The graceful, curved Art Deco glass sconces that once graced the interior of each booth have been replaced by small brass lampshade fixtures. Granted, as von Eckartsberg pointed out, the previous sconces were not original from the 1930s but reproductions in the Art Deco style added along the way. Still, the swing lampshades now in the booths would seem more appropriate as bedside reading lights at a Hampton Inn.

The bells to ring the waiter have been left intact, even in their non-working condition, but the rails that once held the privacy curtains for the booths have been over-polished. A press release announcing the reopening in October explained that “marble and brass were selected for working surfaces because the added character from the patina will help the space continue to age gracefully over the coming years.” The previous fixtures seemed to have enough of their own patina, and it’s sad that many have been chucked out for the sake of new “faux” old.

The previous ceiling fixtures also were not original to the building. Still, the discarded white milk glass lights, in the skyscraper shape popular in the 1930s, had era-appropriate ceiling fans attached and were more graceful than the new cheap-looking ceiling fixtures. A set of shorter, thimble-shaped brown speakers, alternating with longer rectangular white lamps outlined in steel, are trying to be Deco but not quite succeeding. Replacing the mahogany workstation that separated the kitchen door from the dining room is an out of place floor-to-ceiling meshlike charcoal drape.

Perhaps the saddest element of this remodel is the repainting of the gorgeous back bar, which previously seemed to glow with the reflection of the bottles and glasses in the sheen of the polished mahogany, with a row of tiny dentils trimming the top. The new bar, like the table tops in the booths, is covered in white, veined Carrera marble — a more utilitarian surface, especially for wet bar drinks, but a chilly and less comforting surface without the warmth of the wooden bar.

The Elite, along with the Tadich Grill, Sam’s Grill and the Far East Cafe in Chinatown, are among the few remaining restaurants in San Francisco with vestiges of their original interiors, with wooden privacy booths, well-worn bars and vintage neon signs.

Chun and his design team did not rip the restaurant down to its studs, and have left the bones of the original restaurant mostly intact, if painted gray. The current design trend is to repaint any and all woodwork, instead of stripping and refurbishing it. Sadly, this deplorable trend is the easy way out for most interior designers, as it probably was for the Elite, resulting in a space now bereft of decades of warmth.

Therese Poletti is the author of Art Deco San Francisco: The Architecture of Timothy Pflueger and the preservation director of the Art Deco Society of California.

Filed under: Art & Design, Landmarks