GOOD WORKS | FRANCINE BREVETTI

When Luis Garcia was 13, he thought robbing people was normal. Now, at 22, after multiple incarcerations, he sees working an honest job for a decent living as normal. He turned his head around with the help of the Success Center, a nonprofit at 1449 Webster Street providing vocational and education services for area youth.

Garcia grew up in the Mission District with his widowed mother and three siblings. While he wasn’t in a gang, he and his contemporaries repeatedly accosted people on the street. He says part of the reason he robbed others was that he needed the money. “And for thrills — little dumb stuff,” he says. “My friends were doing the same thing. I grew up thinking it was normal.”

Garcia was in detention on and off at the Juvenile Justice Center. He estimates he was at liberty only about three months during his adolescence. At one point, he was sent to a group home in Pennsylvania where he trained and was certified in welding. He returned to California when he was 18.

♦

He meant to find honest employment, but had no idea how long it would take to make that happen. And he needed money. “So I did some of the same stuff again,” he says.

This time juvenile detention was not in the cards. Since he had been a repeat offender and was 18, he was treated as an adult and sent to jail for nearly four years. He had one strike against him.

“This time it wasn’t so easy. They didn’t treat you so nice,” he says. For 23½ hours a day, there was nothing to do but reflect and read. “They say you’re in a cell, but your mind is free,” Garcia says. He took hope from that snippet of wisdom.

Luckily, he had more than that to keep him going. He had a sweetheart.

While his mother was distressed about his life choices and direction, Magrisel, whom he had known since elementary school, had not given up on him. She wrote him letters and visited once a week. He called her frequently from behind bars. A single mom with a son, Magrisel pressed him to raise his standards and turn his life around.

They married while he was in prison. “My main inspiration was my wife,” he says. “I wanted to be a better role model for her son — our son. When I grew up, I didn’t have a father. He passed away when I was 7. I wish I’d had someone to guide me along the way.”

When Garcia got out of jail last fall, he had successfully reimagined himself. He snagged a minimum wage job in food service with Boudin Bakery. After just a month, he found a better job with Merrell, a purveyor of sport and hiking shoes. He was feeling pretty good about himself. But then Merrell closed and he lost the job.

A friend then introduced him to Western Addition Neighborhood Access Point, one of several programs across the city supported by the Success Center and San Francisco’s Office of Economic and Workplace Development. It includes a career center offering job training and placement services.

He hoped the Success Center would help him get a position as a security guard. But since he was already certified as a welder, center manager Patricia Tu thought differently.

“We sat down and talked about his goals,” she says. “Since he was already working, it made sense to find him a better job and a career path.”

And since he was already competent in welding, construction seemed to be a good choice.

Tu notes that construction employers rarely find criminal records as an obstacle to hiring. “All you need is a driver’s license and a clean drug record,” she says. Garcia qualified on both counts.

♦

The Success Center helped him prepare a resume and learn to present himself as employable. He says that was the most valuable part of his experience there.

Then Garcia, after all those years of batting zero, finally found himself in the right place at the right time. One of the weeklong workshops he attended included lectures on math and financial practices, including credit scores. Another speaker, herself an ironworker, addressed the class. Garcia listened attentively.

“Toward the end of her talk, she asked who wanted to be in the union and I raised my hand. I told her I wanted to be an ironworker,” Garcia says. “She made one call that Friday and by Monday I was at the facility in Benicia and by Tuesday I was working.”

Today Garcia is grateful to the Success Center.

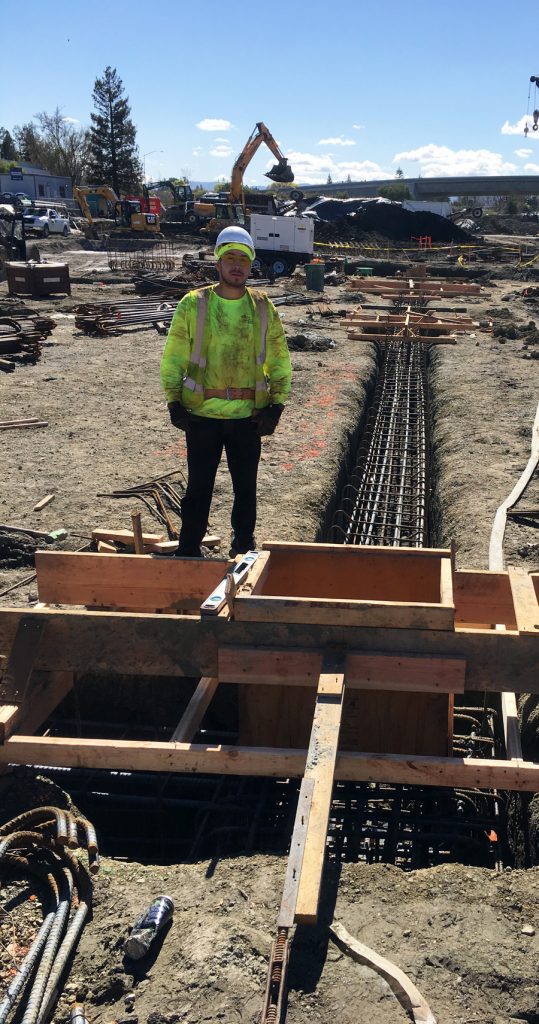

He is now working as an apprentice for Mission City Rebar, based in Livermore. His supervisor Greg Yost says Garcia has lots of energy. “We look forward to seeing him get up to the next level quickly,” says Yost.

“I’m super excited,” Garcia says. He envisions a future when he can buy a house, have more children and in a few years become a journeyman, all thanks to the intervention and support of the Success Center.

Even better, after seven years he can appeal to have his record expunged. And then he hopes to go on to firefighter’s school.

“My mother is very happy and proud of me,” he says with a smile.

“WE COULD SEND THEM TO HARVARD FOR THAT”

When Luis Garcia entered the doors of the Western Addition Neighborhood Access Point last December, he gained entree into a wide array of support systems and services. The program is among those Liz Jackson-Simpson leads under the umbrella called the Success Center San Francisco, which focuses on educating and employing marginalized youth. The center was founded 33 years ago by a group of local superior court judges.

“In San Francisco, over 5,000 young people are habitual chronic truants. Over 60 percent of black and brown youth are failing at the ninth grade level,” says Jackson-Simpson. “It costs over $125,000 a year to house a young person in detention. We could send them to Harvard for that amount of money.”

She stresses that San Francisco needs to invest those dollars more efficiently “with education and job training to ready our young people to go into the job force.”

At a cost of less than $8,000 a year per person, the Success Center provides each needy youth with GED instruction, job training, placement services and intensive case management — as well as help paying for test fees, union dues and wardrobe — plus the use of a computer and fax machine to help with job searches.

Jackson-Simpson says 80 percent of the group’s clients graduate. “We find jobs for people who have never worked at the rate of $15 to $20 an hour,” she says. Last year the Western Addition Neighborhood Access Point placed almost 300 young people in jobs.

TacoBar, at Fillmore and California, is among the neighborhood businesses that have employed clients of the Success Center. And 1300 on Fillmore restaurant has hosted “bootcamps” offering hands-on training in food service.

— FRANCINE BREVETTI

Filed under: Good Works