LOCAL HISTORY | LIV JENKS

Sunnie Evers had been living at 2302 Steiner Street for nearly a decade. One day while she was standing in front of her house, a woman stopped to talk. She told Evers that Adolph Sutro — land magnate, capitalist, philanthropist and short-lived mayor of San Francisco — had built her house for his mistress. The woman, who Evers believes was Sutro’s granddaughter, pointed across the street to Alta Plaza Park and said Sutro designed the park to look like the wedding cake his mistress would never have.

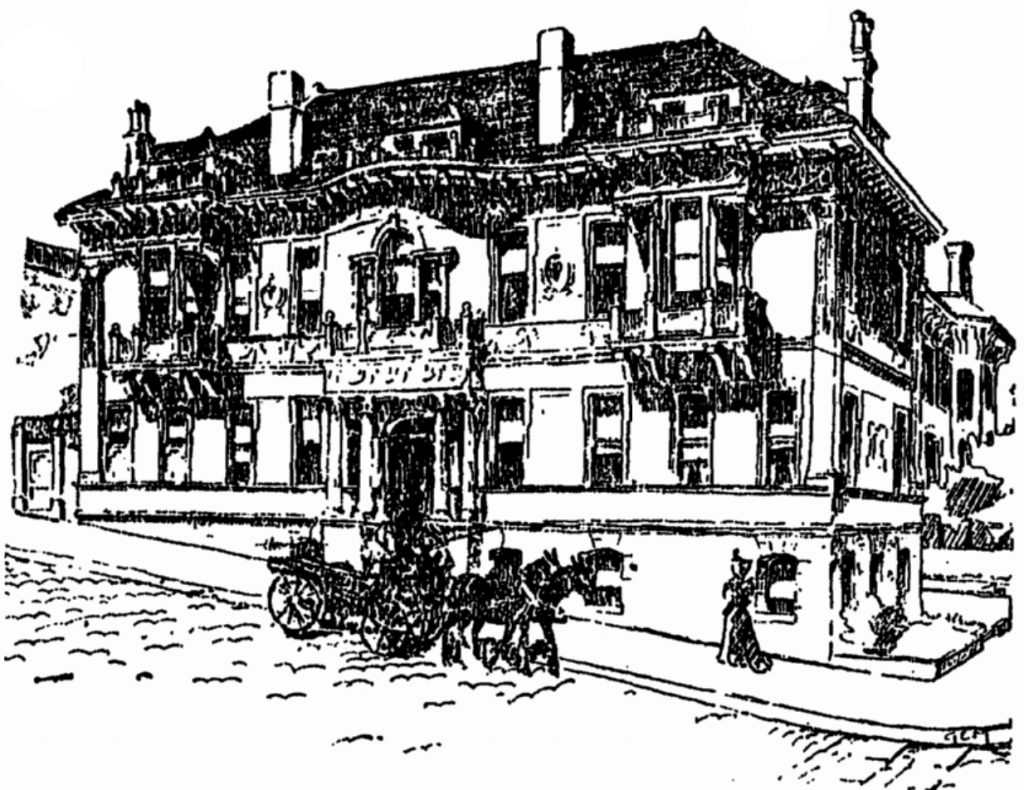

Built in 1896 on the northeastern corner of Steiner and Clay Streets, Evers’ house was designed by an obscure duo of architects, John Laferme and Otto Collischonn. The house has elements of both the Colonial Revival and Queen Anne styles popular in the 1890s. The entrance is on the long rather than short side of the lot, allowing the house to take in the full glory of Alta Plaza. Two porthole windows afford views of the former rock quarry, which had been newly transformed into a park when the house was built.

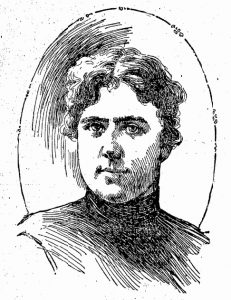

Evers describes the original interior as “very feminine and delicate,” with mantels and fireplaces carved with cupids and floral patterns. She found remnants of the original pink wallpaper when remodeling the kitchen. The feminine touches suggest the house was built for a woman, and it was. The first occupant was Clarise “Clara” Kluge, who had a tangled and storied past with the Sutro family.

♦

In 1851, Adolph Sutro immigrated from Aachen, Germany, to San Francisco, where he began building his fortune. Sutro lived in poverty during his first few years in San Francisco. That changed when he designed the Sutro Tunnel, a drainage tunnel that enabled miners to venture to further depths to uncover vast amounts of silver ore in Nevada. With his $5 million profit, he acquired a twelfth of San Francisco’s acreage.

Sutro married his first wife, Leah Harris Sutro, in 1856, and they had six children. Then in 1879 Mrs. Sutro caught her husband in a hotel room with a Mrs. George Allen — a scandal covered in the city’s newspapers. Sutro admitted he had visited Mrs. Allen’s room, but denied the allegations of infidelity. Mr. and Mrs. Sutro promptly separated.

Clara Kluge met Adolph Sutro in 1890 while working as a seamstress at his Sutro Heights estate. She was 30 years old. When Kluge left her job at the estate, Sutro provided an apartment for her.

Following Leah Sutro’s death in 1893, Kluge claimed she married Adolph Sutro, then 30 years her senior, in the presence of a witness, though there was no written record of it. In an interview with the Chronicle on March 10, 1898, she also alleged that she was Sutro’s niece and that “the marriage between uncles and nieces seems to be becoming quite fashionable.”

In 1892, Kluge gave birth to a son, Adolph Newton Sutro, and a year later to a daughter, Adolphine Charlotta California Sutro. Kluge claimed that her children were not named after their father, but that she had merely selected common German names in accordance with her own heritage. The Chronicle reported on March 10, 1898, that both children bore “a very striking resemblance to the Sutro family” and that the two children called Sutro “Papa.”

♦

In October 1896, Kluge filed a building permit to begin work on the property at Steiner and Clay. She bought the lot from William Crane Spencer for $5,500, the current equivalent of $154,700. Sutro oversaw and paid for the construction of the house. Upon its completion, he gave Kluge money to furnish it. The house had 17 rooms, raw silk curtains, inlaid mahogany floors and carved mantels, most of which still remain.

Kluge attracted a great deal of neighborhood attention when Sutro began visiting her and the children at their new residence. His visits ended a year prior to his death as his mental state deteriorated rapidly. He died in his sleep on August 9, 1898.

Kluge sold the Steiner Street house the year Sutro died, claiming she couldn’t pay the mortgage. Though the Chronicle valued the house at $16,000, the Call reported that on June 5, 1898, Kluge sold the house to Annie E. Bier for a mere $10. The Call also reported that, in the same transaction, Kluge bought property at Grattan and Stanyan Streets from the Bier family for the same price of $10. Kluge never lived in that house. Instead, she resided at 1919 Vallejo in a more modest situation than her former house on Alta Plaza.

Sutro had drafted a will and trust, both of which were held invalid, and a lengthy legal battle ensued over his estate, pitting Kluge and her children against Sutro’s other surviving children, along with dozens of relatives and survivors. Both sides claimed Sutro had made a later will, though no one could produce it. Kluge argued that she and the two children were legally entitled to the estate property as his surviving spouse and children.

♦

The drawn-out battle over Sutro’s estate came to a close in 1902 when Charles Sutro and Emma L. Merritt, two of Sutro’s children, offered Kluge a settlement of $100,000 — the equivalent of $2.8 million today. She accepted.

As for the part of the tale that Sutro created Alta Plaza Park as Kluge’s “wedding cake,” it proved untrue. Alta Plaza was designed by parks superintendent John McLaren in 1888.

Filed under: Landmarks, Neighborhood History