By BARBARA WYETH

There was a brief time on the San Francisco art scene when artwork done on color Xerox copy machines was hot — the latest thing, de rigueur for experimental and accomplished artists, and for novices as well. The Fillmore was right at the center of all the excitement.

The neighborhood had a long tradition of welcoming musicians and artists. That had begun to change with redevelopment, the Geary expressway and gentrification, as Fillmore Street became an upscale shopping district for residents of Pacific Heights. Painterland, a loose collection of artists who gathered in and around 2322 Fillmore in the 1950s, was essentially over when Jay DeFeo and her behemoth painting The Rose moved out of the building in 1965.

In the mid-70s, however, some remnants of that bohemian spirit remained. The street was still eclectic and diverse, with small service businesses, one-of-a-kind boutiques, art galleries and framers, Japanese sushi shops and bars with live music. It was in this milieu that Barbara Cushman, a native New Yorker, opened A Fine Hand at 2404 California Street, now home to Smitten Ice Cream. Initially, her shop offered fine writing implements and supplies for lefties — the proprietor being one — as well as handcrafted goods and fine art. Cushman had worked in ceramics and collage art and had an avid interest in all forms of artistic expression.

Copy art was just beginning to show up in alternative art spaces. Work was created by putting objects on the glass of a copy machine and producing an image. The shape of the object, the amount of light reaching the surface and the distance of the cover from the glass all affected the final image.

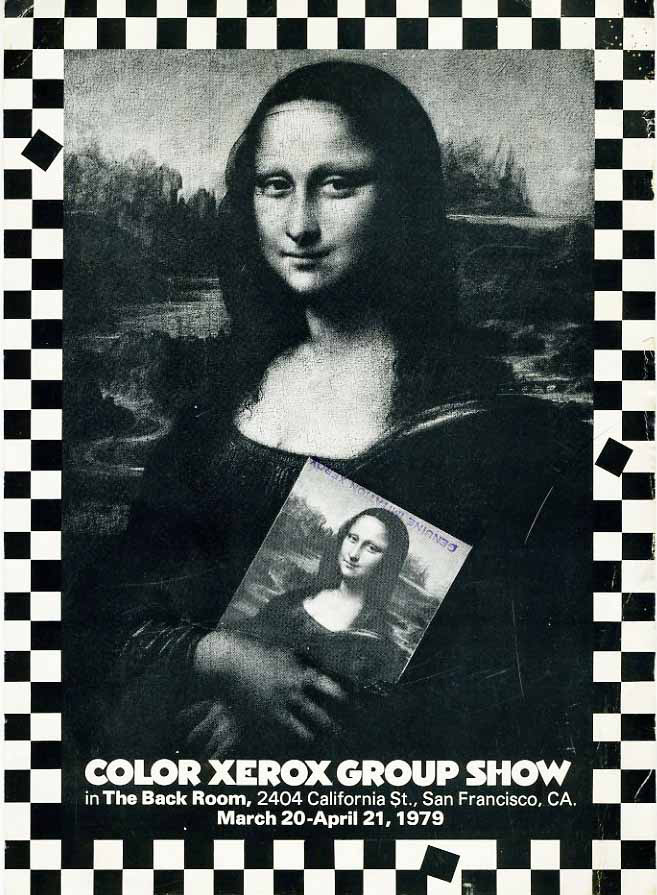

Cushman, ever on the lookout for the newest trends in artmaking, had one of the first exhibits of color copy art in San Francisco at A Fine Hand with a show of postcards by Loren Partridge, granddaughter of the great photographer Imogen Cunningham. In 1979, Cushman opened her Back Room Gallery with the Color Xerox Group Show, which was probably the most comprehensive exhibition of color Xerox copy art produced at the time. The variety of work was impressive, the cheap beer flowed — and the bright plastic color of the artwork was matched by an overflowing and equally colorful crowd.

Cushman soon closed her shop and gallery, but she continued her relationships with the copy artists and went on to produce her Color Xerox Annual for five years from 1980 to 1984.

The format was typically Cushmanesque: a calendar with pages for 13 months, a guest artist each year, and a bonus of some kind, often a postcard by a selected artist, on the back cover. One year, the bonus was a “barf bag” from an airline. In 1984, it was a page from George Orwell’s novel of the same name.

More than 100 artists were invited to participate. They were mostly from the Bay Area, but Cushman solicited artists from all over the United States and beyond. Because the calendars were randomly collated in an edition of 385, no two had the same combinations of artists.

Dealing with her astonishing collection of artwork — both her own and that of others — after Cushman died in 2014 has been daunting. Her sister contacted the Xerox Corp. about the calendar project and the company gladly accepted one of the Color Xerox Annuals for its archives. From that donation, curators at the nearby SUNY at Brockport developed an exhibit in the fall of 2015 called the “Immovable Camera” built around the Color Xerox Annual and concentrating on Bay Area artists and work from the 1970s and ’80s.

This month, CEPA Gallery in Buffalo, New York, will present an expansive exhibition of copy art, with a major portion of the show devoted to California artists, most of them contributors to Barbara Cushman’s Color Xerox Annuals from the ’80s. The exhibition, titled “Fast, Cheap & Easy: The Copy Art Revolution,” will be a broader retrospective of the medium and will include more than 100 artists from the 1960s to the present, in addition to the calendar art. It continues from September 14 through December 15.

In 1982, Hal Fischer wrote in a review in Artweek magazine: “In the worlds of art and photography, copy art has the status of an illegitimate offspring.” A recent exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, collections and archives in France and Spain, and the upcoming show in Buffalo all seem to signal that this short-lived phenomenon that Cushman first championed at California and Fillmore might finally be getting its due.

PUNK WAS BIG AND COLOR XEROX WAS ALL THE RAGE

I met Barbara Cushman at the North Beach Photo Art Fair in the mid-70s when she still had her shop at 2404 California, just a few steps from Fillmore. I was showing traditional and hand-tinted photographs, and we became art buddies and dear friends from then on. I don’t recall seeing any copy art at that fair, but I had heard the buzz about color Xerox.

In 1978, my painter friend Diane Best and I opened the Postcard Palace in North Beach, an art postcard store based on a shop called Untitled in New York’s Soho district. Best and I were both artists and avid postcard collectors, but we wanted our store to reflect more of a San Francisco spirit. And we wanted to support local artists. Punk was big, mail art was big — and color Xerox was all the rage.

Barbara Cushman was already on it. After her iconic show in 1979, she gave up retail and embarked on her equally iconic calendar project. Meanwhile, Electro Arts, a studio and gallery for copy art, joined forces with the Postcard Palace, bringing along its color Xerox copier. We were working with artists and experimenting with all things possible on this amazing machine.

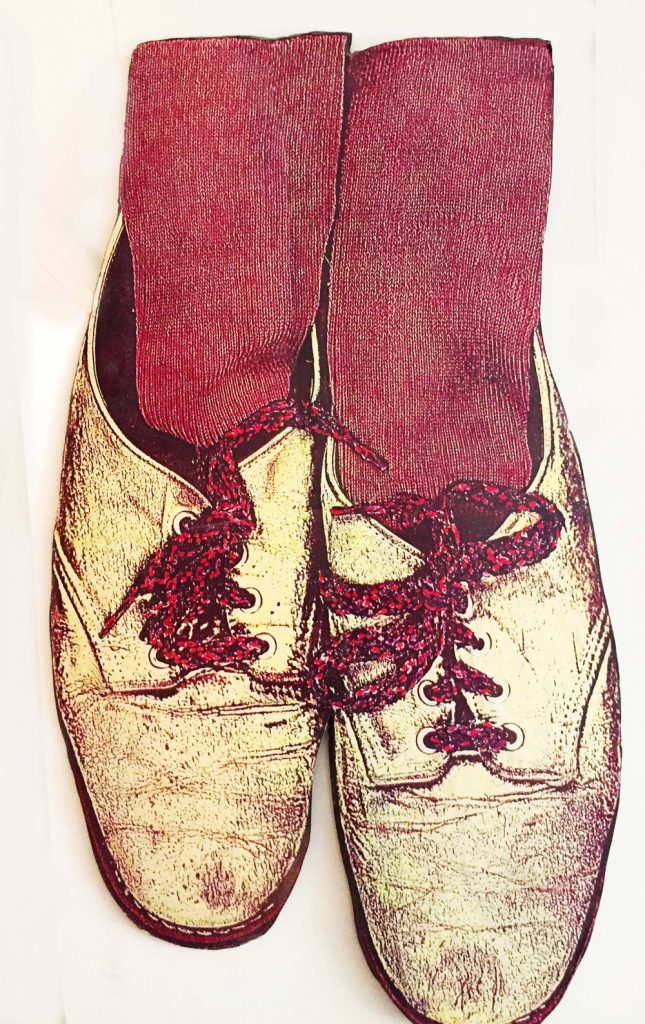

I was making images by laying actual objects on the platen of the copier. I was totally intrigued by the brilliant color, texture and detail captured by the copier. I started copying my clothing, a favorite pair of shoes and old never-worn anklets I found at a thrift store with their “Women’s Work” label and tags still intact. It was my way of preserving objects that amused me, that I liked, that I knew wouldn’t last forever. And it was fast — especially compared to shooting with a camera, developing, printing and then painting with oil paints, which is what I had been doing.

I was hooked.

Just framing the prints made on the copier seemed too tame for all that plastic color and jive, so I began mounting them on foam core, then cutting out the shapes so they would “float” on the wall. Then I wanted to see those mundane things bigger, oversized, ludicrous. I began to enlarge them through a series of steps and a lot of handwork, puzzling together pieces until a pair of shoes became two or three times life size.

I’ve been asked to send some of these to the “Fast, Cheap & Easy” exhibition of copy art opening this month in Buffalo, New York.

Computers, digital cameras, scanners and all the associated technology very quickly changed image making forever. The ease and speed is reminiscent of the color copier, but it seems so much more refined and tame than the luscious layers of heat-fused shiny ink that we got on those color Xerox copiers the size of washing machines we wrangled back in the ’80s.

— Barbara Wyeth

Filed under: Art & Design