LANDMARKS | BRIDGET MALEY

A headline in the November 15, 1922, edition of the Chronicle proclaimed: “Board of Education Cites Pressing Need for Additional Quarters.” The ensuing article provided a long list of “needy schools.” City Architect John Reid Jr., a hometown boy who graduated from Lowell High School and UC Berkeley, was faced with a crisis in accommodating the city’s schools.

Within a few years, he and his colleagues designed almost 40 schools. Reid’s designs included several schools in the neighborhood: Pacific Heights Elementary, finished in 1924 at Jackson and Webster Streets, now San Francisco Public Montessori; Sherman Elementary, also completed in 1924, at Union and Franklin Streets; and Grant Elementary, dedicated in 1922, situated between Pacific and Broadway near Baker Street, now demolished.

Under his direction, his peers designed a number of other neighborhood schools, including the Emerson School at 2725 California, now Dr. William L. Cobb, and the Madison School at 3630 Divisadero Street, now part of Claire Lilienthal.

Born in San Francisco in 1883, John Reid Jr. studied architecture at Berkeley under John Galen Howard, a significant mentor and important early Bay Area architect. When Reid graduated from Berkeley in 1904, Howard encouraged him to apply to the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, the most important design school of the era. Reid easily gained admission, and his Paris experiences would place him among a select few California architects with a Beaux Arts education.

When his Paris studies were completed, Reid returned to a San Francisco that was recovering and rebuilding after the devastating 1906 earthquake. He was well connected professionally, as a former pupil of Howard; and politically, as the brother-in-law of civic leader James “Sunny Jim” Rolph. Reid’s sister Annie married Rolph in 1900.

Reid worked briefly for renowned architects Daniel Burnham and Willis Polk, then established his own practice around 1912. That same year, Reid’s politically savvy brother-in-law was sworn in as mayor. Rolph then appointed Reid as a supervising architect to execute the design for San Francisco’s new City Hall, designed by John Bakewell and Arthur Brown Jr. Reid was also involved in other Civic Center projects and in planning for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition. He became San Francisco City Architect in 1917 and remained in that position until 1927, with school design and construction a high priority; the earthquake had totally destroyed many of the city’s schools and seriously damaged others.

The Ulysses S. Grant School, with entrances facing both Pacific and Broadway, was dedicated on April 22, 1922, with great fanfare. A Chronicle article with multiple headlines read: “Dedication of School Marks Memorial Fete, Story of Surrender of Lee at Appomattox Told to Kiddies.”

The structure, which surrounded a courtyard play area, was U-shaped and occupied a large mid-block lot immediately adjacent to the Cape Cod-inspired Newhall mansion. The building was officially closed on May 6, 1971, when engineers found it structurally unsafe, and demolished a year later. Today a set of stairs evoking the former school entry graces the Broadway side of the lot leading to homes and condominiums since built above.

- Detail of the Sherman School

- Entry of the Sherman School

- Tilework at the Sherman School

- Detail of the Sherman School

Although we have lost the Grant School, Reid’s Sherman and Pacific Heights schools remain neighborhood institutions.

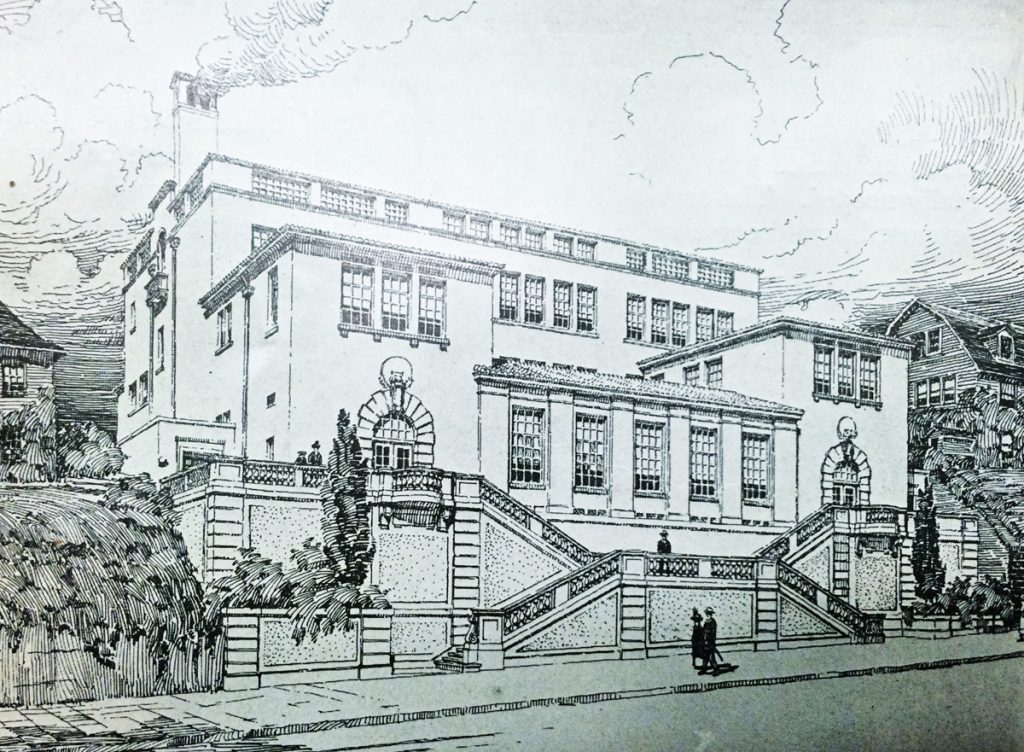

Likely named for another Civil War hero, General William T. Sherman, who had San Francisco connections, Sherman Elementary School on Union Street was designed with Spanish and Mission influences. Situated on a large lot with play yards on either side, the T-shaped building fits the sloping site, with two stories on Green Street while the lower portion along Union Street has three stories. Decorative tile marks the formal entry along Union Street and also adorns the interior.

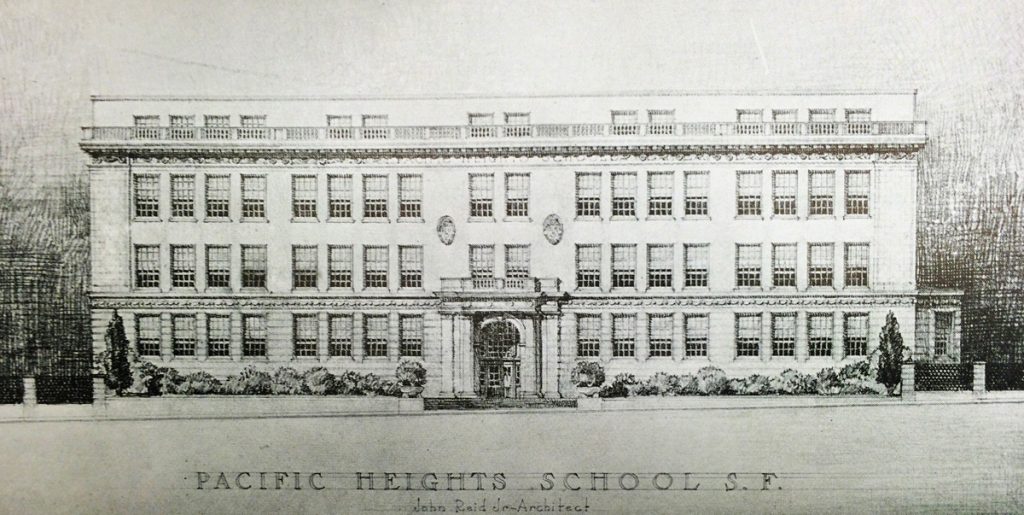

Pacific Heights Elementary School was built in 1924 at the corner of Jackson and Webster Streets. This building is more classically inspired, with a strong rusticated base and an arched entry flanked by columns.

The press and several supervisors hounded Reid from the beginning of his tenure as city architect, leveling charges of nepotism. As early as March 1919, the Chronicle ran an article about the city auditor refusing to pay Reid’s fees because he believed they were illegal. The auditor, Thomas Boyle, asserted that Reid’s brother-in-law “throttled competition and is in direct contravention to two sections of the charter” and that Reid “has been accumulating a comfortable fortune.”

The city architect position was not salaried, so Reid calculated his fees as 6 percent of each project’s construction cost, and collected almost $1 million over his 10-year tenure in the position. Other architects complained about unfair competition and several supervisors questioned Reid’s fees when most architects only garnered about half that amount.

By 1927, Reid’s character was under severe scrutiny. Several city supervisors declared that Reid was never named city architect by official action, and charged that Reid received the lion’s share of the school building work solely because of his relationship to the mayor. Amid the growing scandal, Reid resigned in December 1927. Nevertheless, his lasting designs of schools, libraries, hospitals and other civic buildings remain neighborhood landmarks throughout the city.

Special thanks to Lauren MacDonald, head librarian at the San Francisco Art Institute and a neighborhood resident, for help with research for this article.

Filed under: Bridget Maley, Landmarks