By NIKKI COLLISTER

At Cow Hollow Woodworks, no two projects are alike. The furniture restoration shop prides itself on blending artistry and craftsmanship to give new life to centuries-old antiques, as well as cherished wood objects of any vintage.

“Every single job is custom,” says owner Enrico Dell’Osso, acknowledging the unique history and design of each piece that comes through his doors.

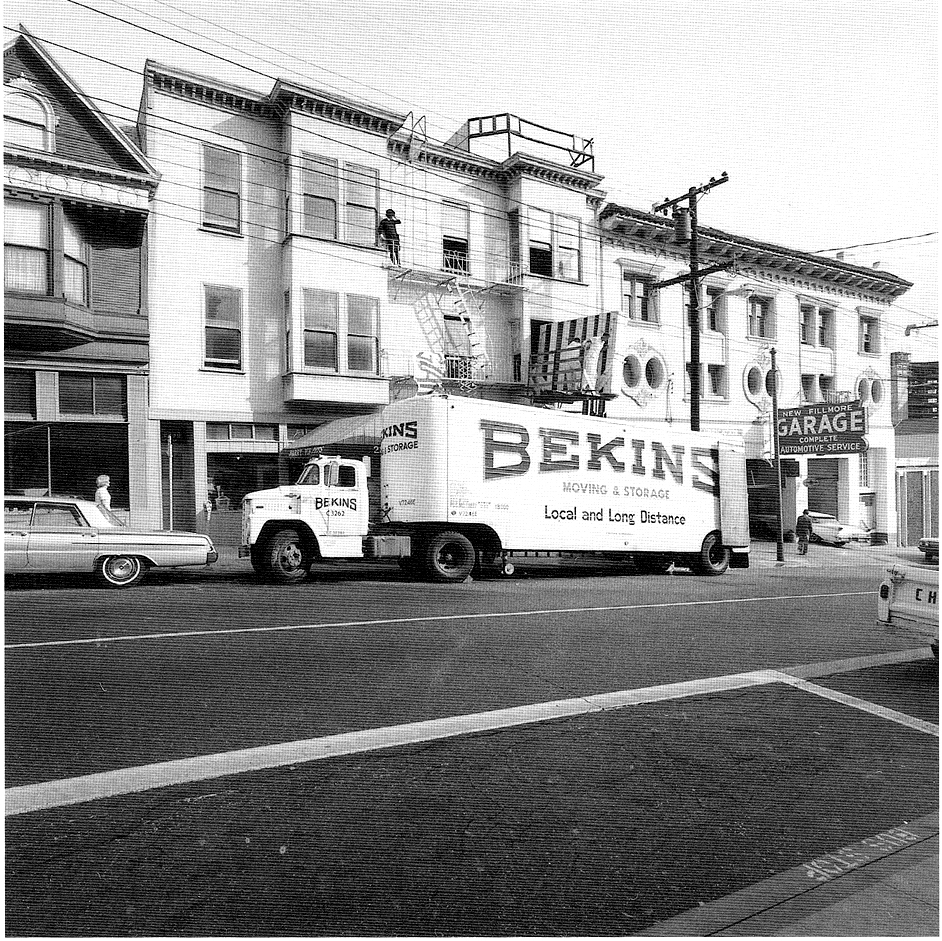

A recent visit to the shop, located on a quiet corner at 3100 Steiner, one block from Fillmore Street, found Dell’Osso sanding the base of a stately wooden table. Antique chairs in various states of restoration hung from the walls, some of them stripped down to their bones, waiting to be revived.

While private collections provide the majority of the shop’s business, their handiwork can be found in public spaces, too. The team at Cow Hollow Woodworks recently finished restoring the entry doors of the historic Gas Light Building in the Marina, bringing its stately oak doors back to their 19th century glory. It was tricky to apply just the right finish to match the interior color, Dell’Osso says, but in the end, it’s this kind of attention to detail that has earned his customers’ respect.

“I was always interested in restoring things,” Dell’Osso says, “and my parents were willing to tolerate the mess and frustration that came with it.”

Once an aspiring art historian, Dell’Osso earned degrees in English and commercial art, and worked briefly as a graphic designer before moving into construction in the Bay Area. During that time he was hired by Ron Hazelton, founder of Cow Hollow Woodworks.

Hazelton opened his shop in 1978. He designed the shop’s handcrafted sign — still displayed on the western face of the building — and would go on to become a beloved home improvement TV host. The shop gained visibility when it was featured in a television commercial for Visa credit cards.

“I had some basic understanding of the trade,” says Dell’Osso, who was initially hired as an estimator, “but the specifics of restoration I had to learn on the job.” And while he didn’t have formal training, his background in art history and hands-on experience in construction provided a strong foundation for the position.

So when Hazleton decided to sell the shop in 1993, he found a willing buyer in Dell’Osso.

Today, a small team of specialists ensures the shop can take on a variety of projects. Some of them focus on preparation: stripping, sanding and filling holes before restoration can begin. Then woodworkers conduct repairs as needed, including regluing chairs and restoring intricate marquetry. Other employees focus primarily on refinishing, using historical techniques to stain and seal each piece. Cow Hollow Woodworks is often sought after for their expertise in French polishing, a practice known among woodworkers for bringing out the natural beauty of the wood.

The team takes care to match the original material and coloring of the piece, whether it’s western black walnut for a Victorian side table or elegant mahogany for an intricately inlaid drawer. Dell’Osso also employs expert painters and gilders on a project-by-project basis, and even a specialist who solely repairs the handwoven rattan caning on chairs.

And while the end result can be a piece of art in its own right, Dell’Osso emphasizes that antique furniture should be enjoyed for its utility, too. When approaching a skeleton of a piece, he says, he’s already thinking about how to enhance its functionality: “We want to optimize it; we want it to be the best version that it can be.”

Through the ups and downs of the industry, Cow Hollow Woodworks has kept a steady and loyal customer base. In some cases, customers from the 1990s have passed on their enthusiasm for antiques to their children, who come into the shop with their own projects.

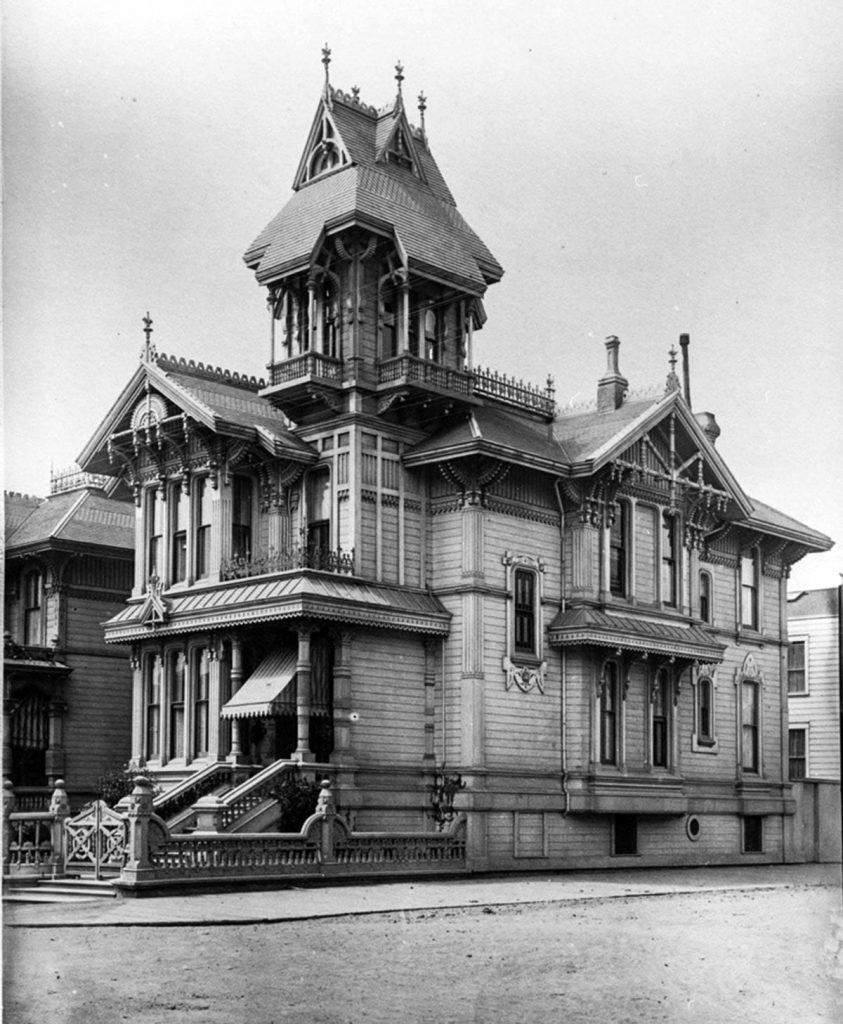

On one recent house call, Dell’Osso was surprised to find a younger customer with a stunning collection of antiques in a home with the magnificence of the Pacific Heights of yore.

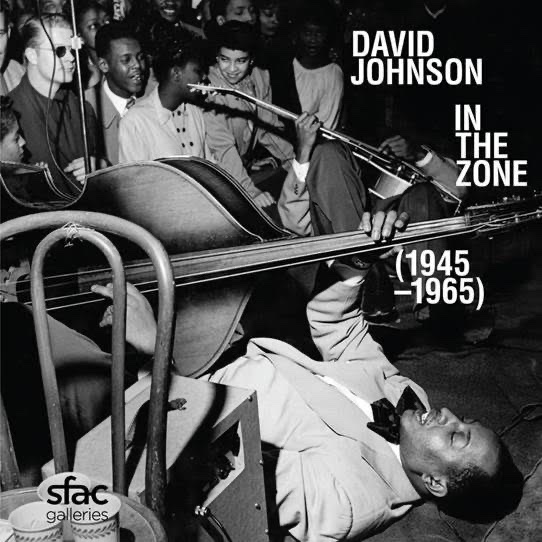

It’s a reassuring reminder that as long as there are those who appreciate the beauty of handcrafted wood furniture — and there are still plenty in this aesthetically-minded town — Cow Hollow Woodworks will remain a vital part of San Francisco’s cultural fabric.

This article is part of a series produced by reThinkRepair, a grassroots group that has interviewed and photographed more than 40 local repair businesses since 2018. Composed of a small team of eco-conscious San Franciscans, reThinkRepair celebrates the art of preservation by sharing stories of local repair shops with the broader community.

Filed under: Art & Design, Home & Garden | Leave a Comment »