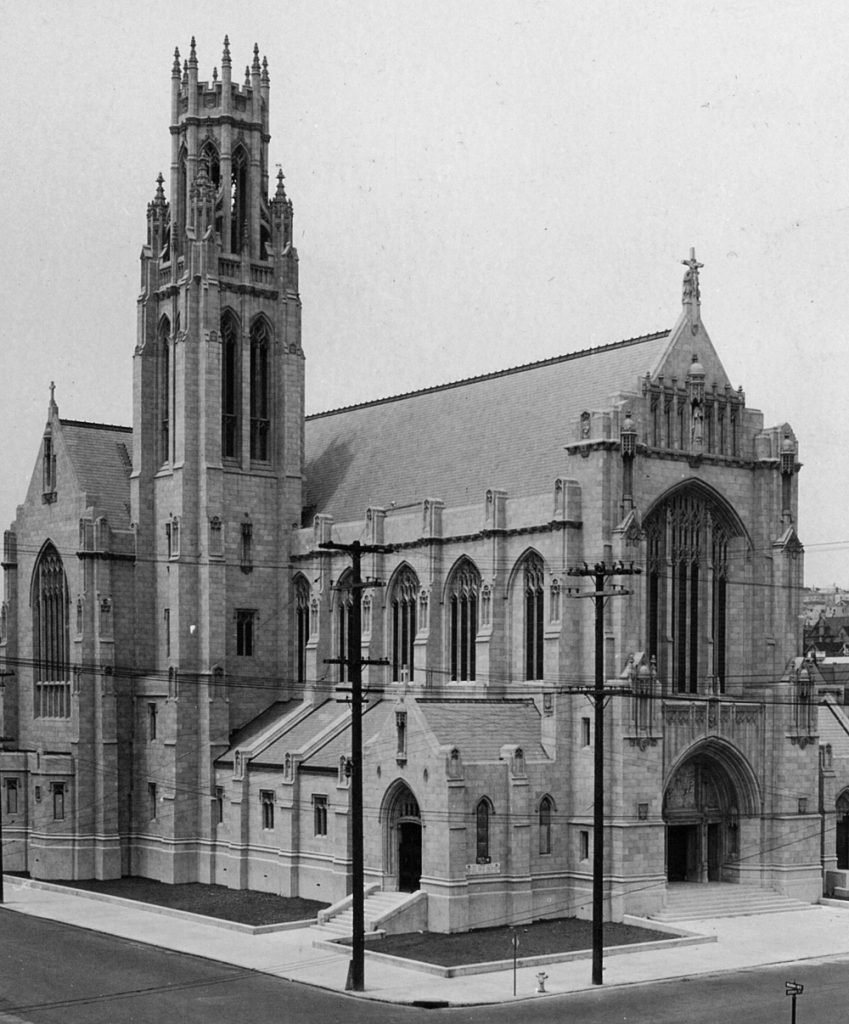

Grand Central Market at 2435 California Street shortly after it opened in June 1941.

ARCHITECTURE | BRIDGET MALEY

Since it opened in June 1941, touted as the city’s “newest drive-in market,” the Grand Central Market, now Mollie Stone’s, at 2435 California Street, has been a bustling neighborhood grocery.

The News Call Bulletin declared that “a program of entertainment would signalize its opening.” A photograph appearing with the article showed a gleaming white building with a black tile base and a Streamline Moderne blade sign. There were two entrances on California Street and one facing west toward the parking lot, for customers who took advantage of the readily available parking. This modern grocery was inserted into a block that had once housed a stately Episcopal church.

The south side of the 2400 block of California Street looked drastically different in 1915 when it was mapped by the Sanborn Fire Insurance Company. At the southwest corner of California and Fillmore Streets was a drugstore with apartments above it. Several other businesses, including a Japanese laundry, were west of the drug store along California Street. Mid-block there were several small single family dwellings and the imposing St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. At the southeast corner of California and Steiner were two additional small-scale store buildings.

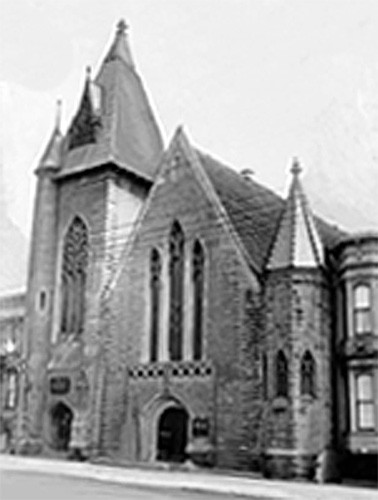

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church

St. Paul’s, designed by the architect Samuel Newsom, was a small ecclesiastical building with a steeply pitched main gable and a red stone facade. The church, which was completed in 1896, burned in 1933, and several adjacent residences, also owned by the Episcopal Church, were damaged by the fire. The church was not rebuilt and the land then became available for commercial development.

The architect of the Grand Central Market was Albert W. Burgren, who was at the twilight of his career when he designed this modern grocery. Burgren, who was born in San Francisco in 1876 to Swedish parents, began a prolific partnership with T. Paterson Ross in 1900 that lasted until 1913. Their projects included a number of hotels and apartment buildings built after the 1906 earthquake, as well as the iconic Sing Fat Building in Chinatown. After his split with Ross, Burgren opened his own office, but continued some collaborative work until Ross was severely injured in 1922 at a construction site. Burgren served in Europe during World War I, returning to San Francisco and working mostly in commercial architecture until his death in 1951 after a long and prolific career.

The Grand Central Market included a meat counter run by the Petrini family, which also had counters at the Lick Super, Sunset Market and Manor Market. Petrini’s was established in 1935 by Frank Petrini, who immigrated from Lucca, Italy, at the age of 12, and was known to have the best meats in Northern California. Petrini’s advertisements are remembered for their inspiring quotes, which also appeared on walls and signs throughout the stores. The quotes were published in a collection in 1992 titled The Proverbs of Frank Petrini: Food for Thought.

The Grand Central Market became Mollie Stone’s in 1998, one of nine stores across the Bay Area. When the new owners remodeled the building, Mollie Stone’s kept the Grand Central blade sign, with some modifications.

Filed under: Art & Design, Bridget Maley, Neighborhood History | Leave a Comment »