ART | JEROME TARSHIS

Manuel Neri, one of America’s leading figurative sculptors, died a couple of months ago. It was no great surprise: He was 91 years old and had been in poor health for a long time. But I felt a particular twinge, because when I moved to San Francisco, in 1968, I found Neri to be an easy, welcoming presence.

Neri was exhibiting at Ruth Braunstein’s Quay Gallery, one of the most respected in the city. Three years earlier he had been appointed to the art faculty of UC Davis, where his colleagues were such Northern California superstars as William T. Wiley, Roy De Forest, Robert Arneson and Wayne Thiebaud. As a relatively major Bay Area artist, he had definitely arrived.

His earliest work had been in cheap and almost pointedly unpretentious materials: cardboard, newspaper, cloth and plaster. As his career and reputation grew, he moved on to bronze and marble, which are considered noble materials. Eventually he bought a studio in Carrara, around the corner from Michelangelo’s house, where he could work with marble from quarries that dated back to ancient Roman times.

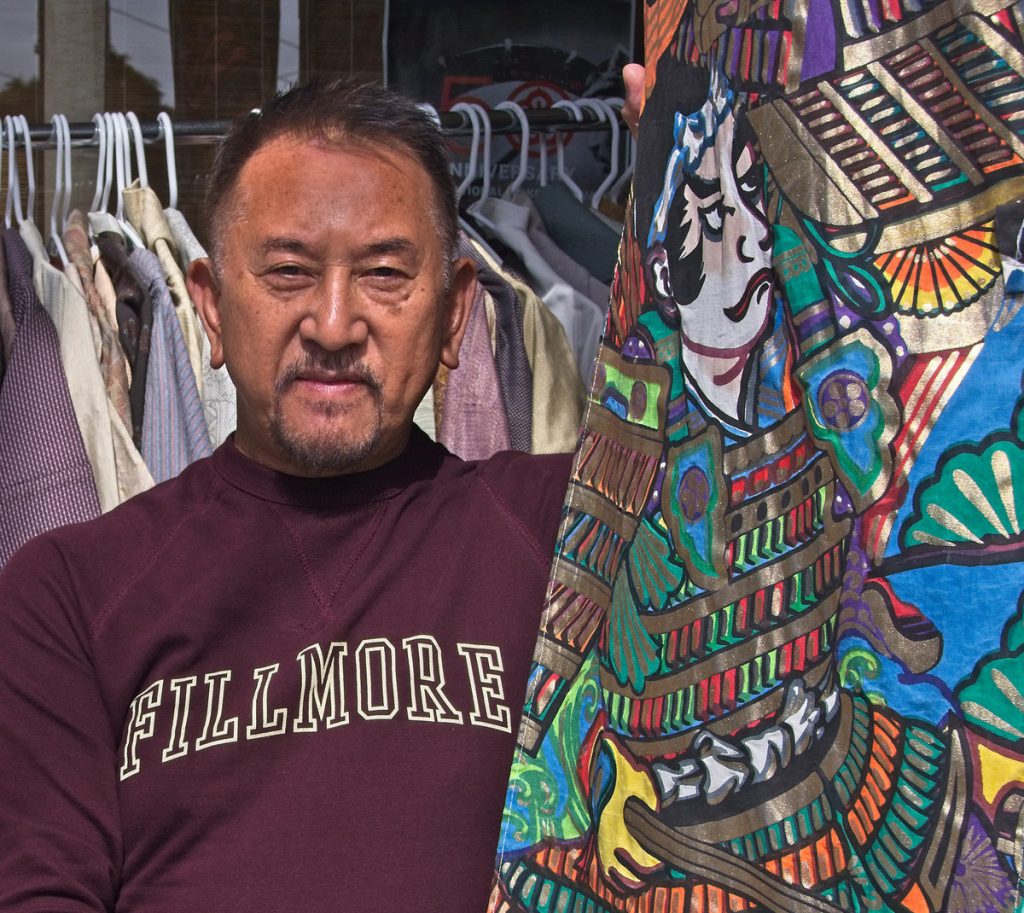

Today his work is in the permanent collections of major museums in the United States and elsewhere in the western world. But his career had humble beginnings, and his earliest exhibitions were in the resolutely noncommercial galleries that made Fillmore Street a major center of artistic innovation during the 1950s and ’60s. When Bruce Conner founded his deliberately odd artists’ group, the Rat Bastards Protective Association, sometime in late 1957 or early 1958, Neri was one of its first members.

He lived on Fillmore Street for a short time. In 1959, when the painter Bill Brown separated from his wife, fellow painter Joan Brown, and moved out of their studio at 2322 Fillmore, the legendary Painterland, Neri moved in with her. But they soon relocated to North Beach, where they eventually married.

•

It was almost an accident that he became an artist at all. He was born in Sanger, an agricultural community, in 1930. He and his parents, immigrants from Mexico, found themselves employed as migrant farm workers after two of his father’s business ventures failed. In 1939, after his father’s death, his mother got a good job in Oakland and the family was back on its feet.

He decided to become an engineer and enrolled for preliminary courses at City College of San Francisco in 1950. Hoping for an easy A — or at least that’s the story he told — he took a course in ceramics and found himself fascinated by the possibilities of art. Although he went on to study engineering at Berkeley, his eyes had been opened to other possibilities. In 1952 he transferred to California College of Arts and Crafts. In 1957, after military service in Korea, he enrolled at the San Francisco Art Institute.

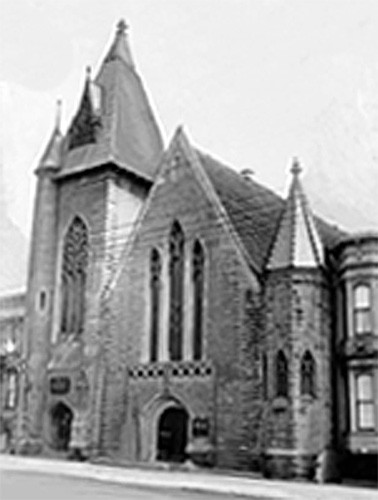

Neri’s first exhibition, while he was still a student, was a two-person show at the Six Gallery, at 3119 Fillmore, in 1956. In 1959 he had a one-person exhibition at the Spatsa Gallery, on Filbert Street off Fillmore, followed by another in 1960 at the Dilexi Gallery, then located at 1858 Union Street, between Octavia and Laguna.

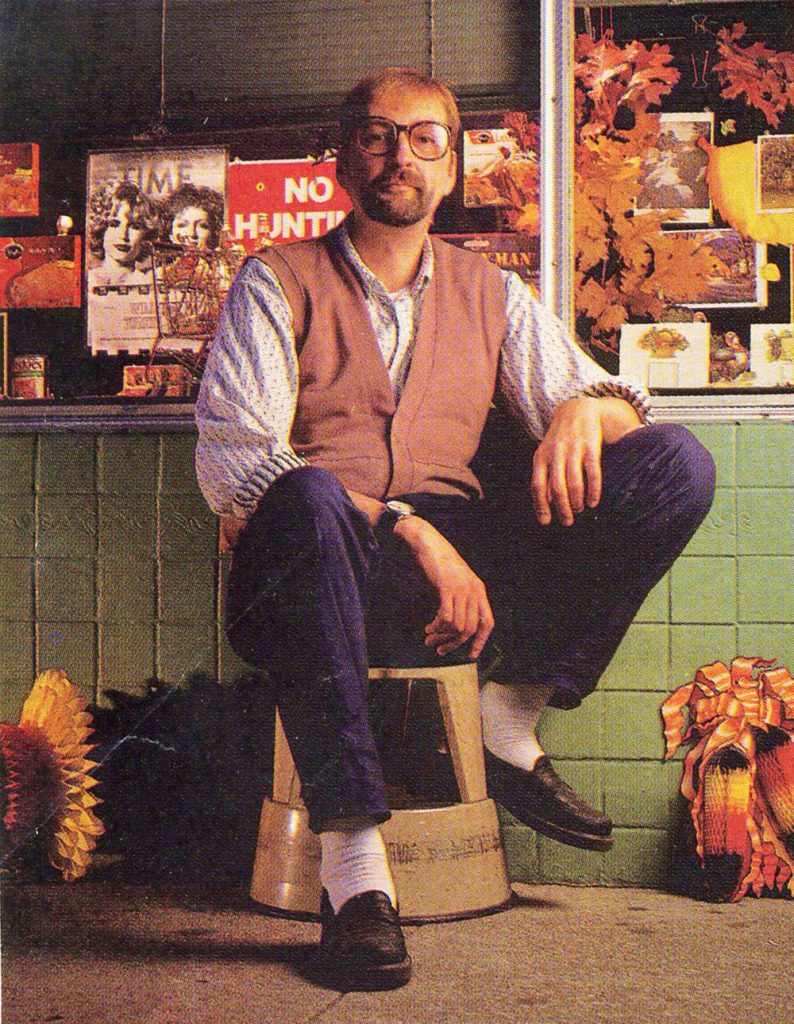

From the beginning of his career, Neri was in the right places and attracted the right kind of notice. Reviewing his very first sculpture show, Alfred Frankenstein, then the art critic of the San Francisco Chronicle, spoke favorably of the work and also discussed the philosophy that seemed to inform the Six Gallery in general and this show in particular: “The group that runs this institution commits itself to exhibiting not only the successes and matured achievements but the half-steps, blunders and fumblings by the way.” Frankenstein had mixed feelings about that. “This emphasis on process, on the doing rather than the thing done, is displayed in an extreme form in the 6 Gallery’s current show. The whole thing is both fascinating and a little appalling.”

•

More than 60 years later, I am happy to add that even when Neri was working in marble and his sculpture was both carefully composed and informed by long study of the European figurative tradition, he managed to retain something of the air of youthful spontaneity that characterized so much art made on Fillmore Street in the 1950s.

As I might have imagined from seeing his work, Neri in person had nothing of the presence of a major art world figure, although by the late 1960s he was well on his way to becoming one. I would look at him, he would look at me, and it felt like a naked soul looking at a naked soul.

EARLIER: “For a time, Fillmore was home to a circle of artists“

Filed under: Art & Design | Leave a Comment »