By JAMES BROGAN

The Donut Hole doesn’t fill up with people by accident. Everybody has a reason for coming in, for stopping to sit down, or buying a cup of coffee and a glazed to go. The numbers change according to what time of day it is.

In the morning, from 6 to 8 or 8:30, the place is like an anthill. Steve has to keep two people working behind the counter, and somebody out in the room cleaning off the tables. All the customers are in a hurry, fueling up before they go to work.

Later in the day it’s a different story. Everybody with a real job is at work, and the place is left to another set of people: people who don’t work, or people who don’t work regular hours, or students or old people or artists, or just people looking for someplace to sit.

I go down there every once in a while myself in the morning. I don’t like to do it very often because, if I sit there drinking coffee for a couple of hours, by the time I get back to my apartment my hands are shaking and my mind is running so fast I can’t use it. Once I sit down in there I might as well kiss off the day because I won’t get any work done. So unless I’m doing laundry or something, I don’t go in.

At noon it gets busy again with people trying to make a meal out of junk food. A crowd of high school girls comes in from St. Rose Academy on Pine Street to smoke cigarettes and pretend they are grown up. They sit around in short wool skirts, crossing and uncrossing their legs for anybody who might be walking by on the street.

After noon, business slows down again, and except for a half-busy time between 5 and 6, the rest of the day leaves quite a few empty tables for people who don’t have anything special to do. That’s when the chess board comes out. At first, it’s just Kenny waiting for somebody to play him. He is the only one with a board and pieces.

The rest of us find out about each other playing against him. Every once in awhile Kenny gets up and lets a couple of us play a game by ourselves, and gradually we get interested enough to want to play even when he is not there. One day, the Donut Hole gets a chess board of its own. I don’t know where it comes from. Maybe Kenny buys it because he gets tired of waiting to take his own set home. Or maybe he just decides to leave the one he has.

We keep it in the back room on the shelf, with the pieces in a small white paper donut sack. If you want to play you just ask the guy at the counter, and he brings it out for you. It doesn’t seem to belong to anybody. I doubt if Steve even knows it is there.

You can play chess for hours without spending any money. A game holds a table down better than a cup of coffee does, and makes people think what you are doing is important. I have gone for weeks at a time several days a week without spending a nickel. I guess even if I did want something I wouldn’t have to pay for it because I work here part time. Everybody works here part time.

Actually, I am surprised that Alice doesn’t throw the chess players out. Maybe she thinks we make the place look busier than it really is during the off-hours. You know how customers are. If a place looks empty, they won’t come in because they figure something must be wrong with it. If it is already full, then they come in, even if they have to wait. Customers are dumb, but they do spend money. Usually Alice gets rid of the deadbeats.

♦

Kenny

Kenny starts it. He sits next to the pole in front of the doughnut counter with his chessboard open, playing both the black and white pieces in a game against himself. Playing against yourself is hard because you are always cheating to one side or the other, usually the one that’s closest to you, and after awhile you lose interest. So Kenny has the chair toward the window on the Fillmore Street side pushed away from the table a little and turned toward the door, like a trap almost. I walk by the Donut Hole lots of times before I fall into it.

I’ve been curious about Kenny since I first moved to the street. I see him dancing at Minnie’s, or playing ping-pong there in the afternoons, so I know his coordination is good. Anybody who can dance for hours like he does wearing high-topped tennis shoes has to be athletic, right? What I wonder is, can Kenny think as well as he moves, or is he going to spend the rest of his life dreaming about starting in the backcourt for the New York Knicks?

Kenny is about six feet tall and very thin. He usually wears a shirt and slacks—never blue jeans—sometimes with a nicely pressed zipper jacket to puff himself out in the chest and shoulders. He keeps his hair cropped short, except for a few days one time when he has it done up in corn rows. He always looks neat, like he just took a bath and put on clean clothes.

It takes him awhile to get his first game. I suppose people are a little suspicious because nobody has ever opened a chess board in the Donut Hole before, and it takes us awhile to get used to the idea. McGee is the first guy I remember sitting down to play with him. That breaks the ice. For a few weeks it’s just the two of them or else Kenny by himself, but after that you never know who is going to be sitting in the visitor’ chair. It seems like Kenny is playing most of the time, which makes the rest of us wonder if we’re missing something.

Chess is like that. At first, you are just curious: you walk up to see who is winning. If the game is close, you have to study the board for a while to figure it out. Before you know it, you are playing the game in your head, deciding what the next move is going to be, and how the other guy ought to answer it. If they do what you think they are going to do, you nod your head to let everybody know you are ahead of the game, and if they don’t, you can’t wait to sit down and show them how it ought to be played. You and two or three other guys. The player who loses usually has to give up his seat to one of the people standing around. The winner stays until he gets beat. It might be different here because it’s Kenny’s chessboard. Maybe he stays, win or lose.

I am surprised to see how quickly the Donut Hole fills up with chess players. Technically, it is a coffeehouse, I guess, but it is a long way from the places in North Beach where they serve expresso and sit around in wool sweaters talking about Allen Ginsberg. Chess is part of the whole beatnik scene over there, and they use it to impress you with how intellectual everybody is.

On Fillmore Street it’s a different story. Coffee is just coffee. You pay your 21 cents, take your cup, and pour it yourself. You don’t have to speak Italian or French to order it, and you don’t have to be carrying a book bag in order to sit down and play chess for a while. The game here is more like a street fight.

Kenny couldn’t have picked a better spot to get it going. The Donut Hole is neutral ground in the sense that it belongs to all of us about the same amount. It could be anyplace. The room is wide open and there is plenty of light, most of the time some empty tables to play on, and room for people to stand around and give free advice. Since the walls are plate glass along both Fillmore and California streets, you can see right away as you walk past when anything is happening inside. It is always open, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, like an indoor park. So it’s a perfect set-up: all we needed was Kenny to set a chessboard down on one of the tables, and boom! Everybody scrambles to take part in the action.

It happens that the Donut Hole has checkerboard flooring. I don’t know if that has anything to do with it or not, but I wouldn’t be surprised. Years ago, according to Alice, before Steve and his partner bought the place, it was a linoleum store and to show off his merchandise, this guy Larry put down big orange and white tiles about three-foot square. I guess the location wasn’t just right for selling linoleum, and a couple of years before I moved out here, he sold the building and moved his business down to Lombard Street near the Palace of Fine Arts. Steve and Mike just leave the floor the way it is, and the way it is is a big checkerboard.

It’s funny, it makes you feel like you are one of the pieces or something. A pawn or a bishop or a white or black horse in a game that is bigger than the one you are playing. Black against white, like Kenny and me.

The first time I come in to try my luck, Kenny is by himself playing both sides of a game out of a book he is reading. The visitor’s chair is empty.

“Hi,” I say as I walk up to his table. “Do you want to play me a game?”

“Sure, man,” he says, pushing the pieces back into their opening positions at the edge of the board. I pull the black pawns to my side as I sit down. It has been a long time since I’ve played any chess, and as I take hold of each piece I squeeze it a little to help me remember what it feels like: the smooth pawns in the front rank, the knights, the bishops, the castles, and the heavy artillery, the king and the queen. Kenny’s pieces are hollow plastic with no bottom, and have almost no weight to them. My set at home, which my father bought for me when I went away to school, is made out of wood with green felt on the bottom. They are about the same size as these, in a similar style. I like their weight better.

Kenny takes a white pawn and a black pawn in his hands and hides them behind his back while he switches them back and forth so I don’t know which is where. When he brings his fists around toward me, I hesitate a few seconds and point to his left hand. He turns it palm up to show me the white. That is what he was playing when I came in, so we have to turn the board end for end before we can start. White always gets the first move.

I push the king’s pawn two spaces forward because that’s what I always do when I’m white unless I’m feeling pretty confident about my game. Most people play pawn to king-four. With Kenny it’s different, as I find out after a few games with him. He never plays what you expect him to play, but always keeps you off-balance. This is our first game, though, so he pushes his king’s pawn out to meet mine. The standard move.

“My name’s Jim,” I say, putting my hand out over the board.

“Kenny, man,” he answers, shifting a toothpick from one side of his mouth to the other. We shake hands.

Our game lasts a half hour, I suppose, maybe 45 minutes, because I am a slow player and I like to talk. I try to get to know him a little, asking him personal questions as we go.

“Do you live around here?”

Kenny says he does, but doesn’t tell me where exactly. It’s someplace over near Baker and Bush. I move my kingside knight to bishop-three, attacking his pawn; he immediately moves his queenside knight to defend it. I forget what my next move is, because I never know what to do at this point. If I bring out my other knight, I tangle up my lines of attack; if I bring out my bishop, I usually get it chased back to a square where it isn’t any good to me; if I push a pawn, then I can’t get my knight where I want it. I never have figured out how to get my pieces out without getting them all knotted up right in front of my king and queen.

I probably push the queen’s pawn one square, which means I give Kenny the initiative. I fail to attack, so now he can attack if he wants. But all he does is push his king’s knight’s pawn one square, which makes me think he is just killing time because he doesn’t know what to do, either. Bad players push pawns when they can’t think of a good move.

So now I have another chance to attack. Unless it’s a trap of some kind. Maybe he’s got a plan I can’t see, or maybe he is just waiting for me to make a mistake. It’s not a bad idea when you’re playing against me, actually. Just give me some room and watch me throw my queen in the toilet. I ask Kenny another question while I’m thinking.

“Do you work around here?”

He says something I can’t understand exactly. It takes me awhile to get used to the way he talks. I think I heard him say something like “school.”

“Did you say, ‘school?’” I ask him.

“Yes,” he answers, speaking the word so clearly I can’t make any mistake about it.

“Which one, City College?”

That would make the most sense. It’s the cheapest, and the easiest to get in. I’m just guessing, you understand. I’m trying to figure out what Kenny’s story is, and I don’t even know where to start. I can’t even tell how old he is: where does he come from? where is he going? He looks up at me, and for one or two seconds we are looking each other dead in the eyes.

“I’m going out to State,” he says. I’m a little surprised, but then what do I know? For weeks after this I figure Kenny is a college kid, about 20 or 21. I find out later that he is only 16, and goes to Washington High School out in the avenues, he is in an Upward Bound program at San Francisco State, and takes some classes out there for that. I think it was Paula who laughed when I told her Kenny was in college. She knows him better than I do. It takes him a few months to trust me enough to give me a straight answer. I can understand that. I’m the same way.

Kenny is doing this razzle-dazzle on the board with a castle to the king’s side. He has slipped his bishop into the knight-two square behind that pawn I was wondering about. It looks crowded in that corner for a long time, and I can’t figure out why he goes to all that trouble to jam himself up like that.

I mean, I can’t figure it out until I try to blast his king out of there. Then I see what he is doing, all right. That bishop is really solid where he has it. I haven’t got enough hardware to get through to where I can hurt him. Besides, his bishop is dangerous in that position. Kenny has the diagonal covered from corner to corner, and is drawing a bead on my queenside rook.

I should have attacked him earlier, while he was still digging in. Once he gets his defenses set, he can spend all his time coming after me, because there isn’t any way I can get to him. For the rest of the game I get to watch him knock my pieces off the board one after another. I start mushing around, like I always do, pushing pawns and trying to get my feet untangled, and Kenny moves in for the kill. Just before he forces the mate, I tip my king over to show him I can see it coming.

♦

Cleophus

Friday, Cleo comes in and robs the place. Bang! he slams his cane on the formica top of the first table inside the door.

“All right!” he hollers. “Empty your purses on the table!”

I am down behind the counter rearranging the bear claws. Alice doesn’t like to see half-empty trays because the customers will think everything has been picked over. When I hear Cleo shouting, I stand up to look, and see a typical Fillmore street character about 50 or 60 years old, drunk probably, heavy-set, walking with a limp. His clothes are scuffed, cotton pants and an unbuttoned sport coat pushed apart where his belly sticks out. He hasn’t shaved for a couple of days. He is missing some teeth, and as I notice now for the first time, his nose has taken some damage, too. The kind of guy you can find any day on the corner of Fillmore and O’Farrell drinking whiskey out of a half-pint bottle.

“Everybody put your valuables on the table!” he says. He has a deep, raspy voice.

For a few seconds nobody moves, and I’m not sure what to make of it. I don’t think this is serious, but you never know. The Donut Hole does get robbed every once in awhile. Cleo’s left hand is jammed in his coat pocket, and for all I know he could be carrying a .38 in there. Just as I’m trying to figure out what I should do, he pulls out a bicycle horn and shoots two or three people before they have a chance to stand up.

Wook-ah! Woo-kah!

I forgot. Cleophus always carries a bicycle horn.

He starts laughing at the people who thought he was serious, louder than he really needs to. He is pleased with himself. Ron has seen him rob the place before, I guess, so he just keeps scribbling away at poems in his notebook, looking up to smile when the snow is over, to let Cleo know how convincing it was. It is funnier when you know how it is going to come out.

I find out too late that it is not his only song and dance. He comes in one evening just before I get off work and tells me to package up some donuts for him. Free ones. When you work a shift at the Donut Hole, you get to take a box home for free. Usually I just take one or two, if I take any, because they don’t stay fresh long, and I get sick of eating them after awhile.

Cleo says he works the graveyard shift, helping the cooks. I forget their names. He gives me a name—John or somebody—and says he works with him. I wouldn’t know. I only work Friday afternoon from 2 to 7. The bakers don’t come in till 10 or so, and work overnight making fresh donuts for the next day. Once in awhile I come in around midnight for something to eat, or to play some chess, but I never pay any attention to what is going on in the back room. I don’t know if Cleo has been working there or not.

“Who are you?” he asks all of a sudden.

That is a hard question to answer when you try to answer it for somebody you don’t really know. There is not much I can tell him, except my name.

“Jim,” I say. Not that it is any of his business.

“Huh?”

“Jim,” I say a little louder. “My name is Jim. Why?”

“You supposed to be working here?” Cleo asks.

“I think so,” I answer. It’s funny how a question like that makes you wonder. This is Friday, isn’t it? Sure it is. What’s he after, anyway?

“I never seen you round here before,” he says to me, looking at me through a squint. “Where’s Linda?”

“Linda who?”

“Linda!” he says. I guess he means the lady who works here on weekends. The one who took scream treatments in Marin County.

“I don’t know.”

“Ain’t Linda supposed to be working today?”

“No. she isn’t. I work here on Fridays.”

“I thought Linda supposed to be working now.”

He starts walking in a circle, looking around to see who is in the place, then back at me. It is getting late in the afternoon, and most people have cleared out to go home and eat. Only two or three tables have customers at them.

“How long you been working here?” he asks me.

“About a year, year and a half.” I keep answering his questions for some reason.

“Where’s Linda?” he asks again, as if I am hiding her from him.

“How should I know! She doesn’t work here on Fridays.”

Just as I begin to lose patience with him, I remember that Alice did have Linda work my shift last week while I was out of town. But that was the first time and the only time. Maybe Cleo just started last week. It’s possible.

“She works on weekends,” I tell him, wishing he would get lost. Jive-ass.

He tells me to go ahead and pack up a dozen to go.

“You don’t really work here, do you?” I ask him. Now it’s my turn.

“Sure, I do!” he comes back. “What you talking about? I work all night.”

He is telling me he works in the back because he knows I’ll never believe he works at the counter. We both know he’s a wino, but that doesn’t mean he couldn’t be working here. The first time I saw the cooks come in and walk behind the counter, I thought we were being held up. There must be 50 people on the payroll of this place, and some of us never see each other.

Besides, Alice is always firing somebody, or somebody gets mad and quits on the spot, like Jack did the time his replacement didn’t show up on Thanksgiving. Jack calls Steve, tells him he is fed up with waiting, and that he is going to lock up the place and go home. And he does. Steve lives out in Pacifica, and he never works here. Not on Thanksgiving, that’s for sure.

So Jack locks it up and quits. He has quit several times. He comes back, though. If you live in this neighborhood, sooner or later the Donut Hole is going to pull you in. It’s like gravity.

Cleo is picking out the donuts he wants to take with him. Mostly big expensive ones. A bear claw. Two jelly-filled. A cinnamon, roll. A cinnamon twist. He’s jabbing at the case with his cane to tell me what he wants. Now he taps at the apple fritter. Wouldn’t you know? I never make it through the afternoon with one of those unless I hide it in the back. They cost 55 cents apiece, a nickel more than anything else we have, and usually they are gone by four o’clock, if we have any to start with. Today, I’ve been lucky and I’ve got one left in the case. Or did have.

I know Cleo is lying, but I put it in the sack for him with everything else,

He is looking at me kind or sideways, talking to himself as I come back in front of the cash register.

“It’s funny I never seen you round here before,” he says one last time.

I’m not even going to argue with him. It’s too late to get mad. I don’t really believe he has been working here, but what am I supposed to do? Call Alice? She won’t he home yet. It’s not like we’re going to run out of donuts anyhow, and besides, we all give free ones away to our friends. If every donut that went out of this place was paid for, Steve and his partner would be rich.

So I give Cleophus what he wants and watch him limp out the door even slower than usual. As he comes back along Fillmore Street outside our front windows, he is still squinting at me.

Less than one our later, Alice comes in and I ask her about him.

“What! Cleo?” she screams. “Are you crazy? He’s never worked a day in his life.”

♦

♦

Our Lady of the Lone Star

Fay hasn’t kept any girls for a long time. She is getting older, and what with birth-control pills and everything, running a house these days is a losing proposition. Sally Stanford—who got famous at it—moved out of the city years ago and started a restaurant in Sausalito. She keeps some of her red velvet furniture and fancy wallpaper to give you a feeling for the old times, but now she is selling steak and potatoes.

I don’t think Fay ever had her own place. Years ago, according to Alice, she worked out of the Lone Star Hotel on Geary Street across from the Fillmore auditorium. White ladies for black gentlemen. The Lone Star is a good-sized building with some style to it, but like the rest of the block it’s getting kind of run-down by this time. Fay still lives there, as far as I know.

She comes in to the Donut Hole an hour or two after I start my shift, always dressed in evening clothes even though it is the middle of the afternoon. She wears a bright pink overcoat like the ones you see on the racks at the Goodwill store across the street, made out of heavy cloth and reaching about halfway to her knees. The dress underneath is off-white, made out of rayon or something shiny like that, with a high neck and a pleated skirt. On her head, instead of a wig, she wears one of those rubberized swim caps with feathers all over it, either all black or all white, depending on her mood, I guess. It covers her ears, but her long earrings hang down from inside it. On her feet she wears bedroom slippers, the kind made out of clear plastic with fuzz tufts on the toes and low spike heels. Gloria wears bedroom slippers in the Donut Hole sometimes, but hers are just baby-blue flop-arounds made of terry cloth. Fay’s are fancy.

As you might expect, the lady is easy to spot when she is walking down the street, even from a distance. I can pick her out of a small crowd from three blocks away. Her coat is the main thing, especially on an overcast day when it glows against the dark of the old buildings, but you can also tell her from the way she walks. Instead of picking up her feet, she shuffles them along the ground as if her ankles are sore. I suppose she walks like that to keep her slippers from falling off, but it could be that her feet hurt, too. They are kind of puffy.

She is not a beauty, even for a woman her age. She is too heavy, for one thing, and her face is too big through the forehead and cheekbones, with a long nose and a hard chin that keeps you from getting smart with her. She doesn’t smile often, and she doesn’t wear much make-up, either, except for face powder. And bright red lipstick. She draws her lipstick on in a Cupid’s-bow shape, like Jean Harlow or somebody, neat as can be. The only trouble is, her lips aren’t really like that, so the lipstick just paints a valentine around her mouth without ever touching it. She reminds me of one of those big sopranos in the opera, without the horns and the chest protector.

One day, before I started working behind the counter, I found myself walking down the street beside Fay, and I couldn’t resist asking her some questions. She didn’t seem to mind. She used to have some really nice girls, she said, but it got so she couldn’t afford to keep them. She spoke in an English accent because it turns out she is from Australia. Aus-trail-yer, she calls it. She went back to Australia for awhile when business got bad here, but it didn’t work out. Prices in the cities down there are even worse than they are in San Francisco. So she came back, but it was too late everywhere. Everything costs too much now, she says. You can’t make any money running a business these days.

That is the only time I ever talked with her, really. She has forgotten all about it. I’m just a guy behind the counter now, as far as she knows. I wish I had the nerve to ask her more questions about the old days. She probably has a million stories. If only she didn’t look quite so rugged, it would be easier. She’s mad at me now, anyway.

We have this little run-in one time. It starts when I charge her tax on a slush. Up to this time, I always play it by ear, telling the customers a slush costs 20ȼ, or telling them it’s 21ȼ, depending on whether I feel like fooling with the pennies. 30ȼ or 32ȼ for a large. This time I play it by the book, I guess. Fay comes up to the counter, looks at the slush machine, as usual, and says,

“A 30ȼ orange, please.”

I pick a waxed paper cup off the stack, scoodge a couple of shots of orange syrup in the bottom, and fill it the rest of the way with the sloshey stuff that comes out of the machine when you turn the handle. It’s not ice and it’s not soda. I don’t know what the hell it is. Lots of people drink it, though, especially kids. They call it a slurpy.

The syrup comes in six flavors: bright red, bright yellow, bright blue, bright orange, bright green, and grape. It makes my teeth hurt just to look at it. Fay always picks orange.

I put a cupful down on the counter for her, and tell her it’s 32ȼ.

“How much?” she asks, pulling her head back like a chicken.

“32ȼ,” I say.

“They’re 30ȼ, ahn’t they?” she asks.

“No, they’re 32ȼ, counting the tax.”

I point to the hand-painted list of prices hanging from the ceiling above the counter. I only point to this sign in an emergency because half the prices are out of date and some of the things listed we don’t even sell anymore. Steve never gets around to changing the information. Slush is right, thought, so I point at the 30ȼ. The lady is not convinced.

“It says 30ȼ. They’ve always been 30ȼ.”

“They are 30ȼ, but there’s 2ȼ tax.”

“The girl never charges me 2ȼ extra!” she says, and I can see she is getting mad at me. I guess she means Meggan, who works my shift every day except Friday. Meggan or Bea.

“There’s a 6% sales tax on everything,” I explain.

And there is, when we charge it. The problem is, lots of times we let it slide. This must be the first time I’ve ever asked Fay for tax or she wouldn’t be squawking. Most people just pay what you tell them even if it changes a penny or two once in awhile. They don’t pay attention. I wasn’t really paying attention myself. If I had known she was going to get her feathers up, I wouldn’t have asked for the extra 2ȼ, but it’s too late now. I’ve got to go through with it.

The truth is, I never ring the cash register the way I’m supposed to, anyway. At first it was because Meggan showed me how to do it wrong when she trained me in. She didn’t know how it’s supposed to be done, either. After a year or so, somebody taught me the right way to do it—the tax man was getting on Steve about it—but it took so much time I just went back to the way I was doing it before.

Let’s say somebody comes in to buy a doughnut for 22ȼ. I’m supposed to push 22ȼ, then one of the buttons to show what sort of 22ȼ it is: food or whatever. Then I push 1ȼ more and the button that says “tax.” That makes 23ȼ. I mash down on the total bar with the back of my hand; the bell rings, the right answer comes up on the number tags, and the drawer pops open. If the customer hands me a quarter, I hand back two pennies. Very simple. But not as simple as just ringing up 2, 3, total. That’s three buttons I have to push instead of six, and when I’ve got people stacked up who are in a hurry (everybody’s in a hurry when they want to start eating), I’m not going to monkey around trying to push every single button in exactly the right order. Half the time, since I’m saving myself the extra trouble, I just charge them 22ȼ anyway.

If a guy orders coffee, which is 20ȼ, I’m more likely to charge him the penny. Don’t ask me why. Everybody’s got a penny, I guess. It’s still only three buttons: 21ȼ, boom. If it’s coffee and a doughnut, which it usually is, it really gets complicated, unless you forget the machinery and do it all in your head. It’s supposed to go: 22ȼ doughnut (that’s three buttons right there); 20ȼ coffee (three more); 3ȼ tax; and total. Nine buttons! It takes forever. And since I know coffee and a doughnut are going to come out 45ȼ every time, I just hit 4, 5, and total.

This time I don’t know what got into me.

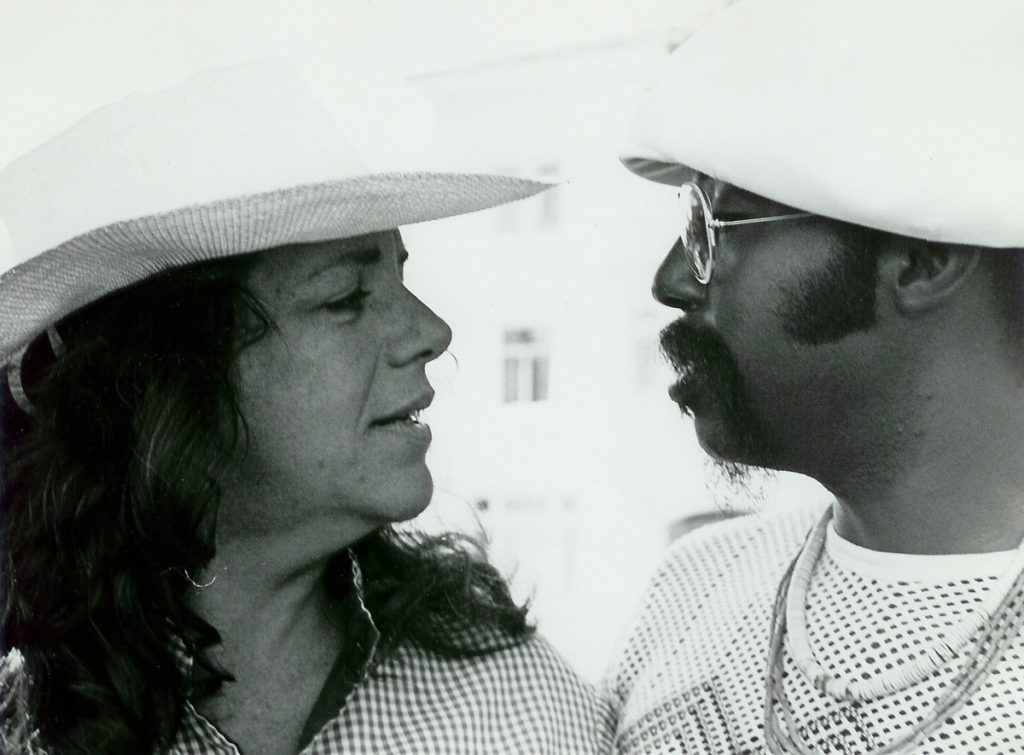

Fay puts two pennies on the counter, snapping them down one at a time to let me know exactly how much too much I’m charging her. She is unhappy and now I am unhappy. I feel like one of those roundheads at the Bureau of Motor Vehicles who always ask you for the one piece of paper you forgot to bring. The temperature in the Donut Hole goes up 10 degrees on both sides of the counter. The lady won’t be coming back for a refill like she usually does, you can be sure of that. When she gets back to her table I hear her start to talk with her two friends—the dapper black guy and the German lady—about what just happened.

“32ȼ,” I hear her say, and then start in about high prices and how the neighborhood is going to the sharks.

When Alice comes in later, I’m still a little upset about it, so I tell her the story. She says we’re supposed to charge tax on orange drinks (I knew she would), and if Fay hasn’t been paying 32ȼ, it’s about time she started. Steve is getting in trouble with the tax people and there are too many freeloaders coming in here lately and if people don’t like it they can go someplace else. Alice knows what to tell me.

A few days later Fay comes in while I’m still busy sweeping the floor. It’s not 3 o’clock yet, so Bea is working behind the counter while I get things ready for my shift. Fay is early today, maybe so she won’t have to deal with me. That young man.

“A 30ȼ orange, please,” I hear her say, as if the world is going to fall back into place. But it isn’t. Alice in the meantime has been getting the troops organized. Bea sets the cup down on the countertop and tells her as sweet as can be,

“That’ll be 32ȼ.”

♦

♦

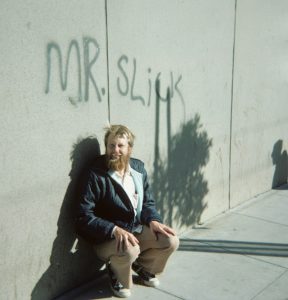

Coates

Stan the egg man told me to watch him. Coates may be a little off in his head, but you don’t want to underestimate him. He’s clever. People think he is dumb because he looks funny—an empty grin on his face, wearing a baseball cap screwed around to one side—but Coates isn’t as dumb as you think.

He is strong, too. I figured that out just by shaking hands with him. He wouldn’t look so funny if he lost his temper. He can make you nervous if he wants.

Half the time he puts on this scowly face. You would think he was looking for a fight, if you didn’t look underneath and see his eyes laughing at you. I suppose to him normal people look serious all the time. If he can keep his face dead-serious, they won’t notice his brains aren’t set in straight with his nose. He doesn’t want the laugh to come out, but he can’t keep it in. I think that’s what makes him look crazed.

Alice kids with him. She doesn’t worry. He will come up to her on the street.

“Hi, Alice,” he will say, with a big smile on his face, leaning close to her and mumbling something you can’t quite hear. Sometimes she laughs, and sometimes she ignores him, and continues talking with her friends. Once in awhile he puts his arm around her, or puts his hand behind her neck and pulls her close to his face and whispers to her. You can see his lips move, but you can’t quite figure out what he’s saying. If you didn’t know better, you would think he was making a pass at her. Alice reacts differently, from one day to the next. Maybe this time she says,

“Oh, no, Coates! Go away. Go away!

Coates doesn’t care. He chucks her under the chin, and says, “Why? What’s the matter?” sort of laughing, and looking at the rest, of us out of the corner of his eye.

“Isn’t it true, huh? Isn’t it true, Alice?”

“Go away, Coates,” she will say again, harder this time if she is not in the mood. At other times, though, she just laughs. And you sit there wondering what’s going on.

One time Alice told me what he says. I guess he always says the same thing when he whispers in her ear like that. And you know what it is? You know what he says?

“You old bag!” he whispers, showing a smile to the rest of us. “You old bag,” he says, like he was kissing her. Alice is around 50, and a big woman, you understand, but nothing like what he says to her. Alice has quite an appetite for men, and a temper, too. I’m surprised she lets Coates get away with it.

Coates works for this older guy who sells produce off a flatbed truck. They drive around San Francisco and park different places. For an hour or two they are just up the street at the corner of Fillmore and Sacramento. Eggs and grapefruit and vegetables. Pretty good quality. I bought some tomatoes once. Coates can count change and everything. He never gets to drive the truck, though.

He stands about 5-11, with dark, greasy hair and a beard he never quite gets shaved off in the morning. Maybe they won’t let him use a razor. He is built kind of slight, although it is hard to tell exactly under his big overcoat. He wears a green canvas army coat about two sizes too big for him, pulled up like a curtain around his waist with a two-inch cotton belt. The baseball cap set on sideways is army green, too. Heavy black oxford shoes on his feet.

When you holler his name, “Hey, Coates!” he always turns around with that grin on his face, his eyes too happy, like a baby’s almost, not tracking just right. He loves it when you kid with him.

His teeth are a mess. They look like he has been chewing the same plug of tobacco for six weeks. Some of them are missing, and the others covered with this greenish-brown, so that when he laughs, and his eyes go crazy, he looks like the north side of a tree. I don’t think he really does chew tobacco. I don’t know what you’d have to do to get your teeth to look like that. Maybe toothbrushes feel funny to him.

One time he comes in to the Donut Hole and doesn’t say any thing. I know what he wants. He always orders the same thing: large coffee to go, no lid. If I give him a plastic lid to cap it with, he just kicks it back at me with his finger, without saying anything. He hates plastic lids.

So I hand him the large empty styrofoam cup, as usual, pick up the 30 cents he has scattered on the counter, and wait for him to grin and say, “How’s it goin’?” But he doesn’t say anything. He just looks at me, frozen-faced, waiting, like I am supposed to notice something.

“What’s wrong, Coates?” I ask him. “You having a bad day?”

He still doesn’t say anything, but jerks his forefinger up toward his face, to show me.

“What?” I ask again. He points toward his left ear.

“Can’t you see it?” he says, barely moving his lips, like he is paralyzed from the neck up. But his eyes are sneering, as if to say, what’s the matter? Are you retarded or something? I look at his face, but I don’t see what he is pointing at. Finally he tells me. It’s his jaw. He’s got another bad tooth and his jaw is all swollen on one side. Now that I know what I’m looking for, I can see it.

“Jesus Christ! Coates,” I say to him. “Are you going to have it pulled?”

“Naw.”

He will just wait for it to fall out, I guess. Pour some extra sugar in his coffee. I suppose he has lost so many teeth by now, he doesn’t worry when another one gets infected. It gives him something to quiz his friends with to see if they’re on the ball. He is almost smiling as he turns to fill his cup at the side counter where we keep the coffee.

“What a dope!” he seems to be thinking.

It’s when he gets over to the coffee pots that I have to keep my eye on him. Stan the egg man told me right away what happens if I don’t. First, Coates pours about three or four tablespoons of sugar in the bottom of his styrofoam cup. Then he takes a coffee pot off the hot plate and pours in maybe a third to a half. Keeping his back to me, so that all I can see is this wall of green canvas, he takes one of the metal creamers and empties it into his cup. If there is still room in the cup, he takes another creamer and empties that.

Then, still turned away from the main counter where I’m standing, he drinks as much as he can in two or three big gulps. And then he takes a third creamer and empties that into what’s left of his coffee, and finally, the fourth and last, if he can—with extra sugar.

If all goes according to plan, and I am busy at the counter filling a white paper sack with “half a dozen a glazed” for some fat lady who has just come in, Coates can empty all four creamers before turning around with a smile on his face.

“Take it easy!” he says as he glides past the counter toward the front door. He walks funny, very smooth, with his feet splayed out to either side.

“Did you see that!” says Stan. “He emptied every goddamn one of the creamers. I watched him do it.”

Stan delivers five gallons of the stuff on Fridays, and so takes a personal interest in what happens to it. It’s not real cream. It’s non-dairy creamer, whatever that is.

“Watch him next time, I’m telling you,” says Stan. “Every time he comes in, he does that.”

I walk over to the hot plates to see for myself. Sure enough, they are all empty, and I had filled them maybe ten minutes ago. I refill them from the pitcher we keep hidden behind the tip-up counter, promising myself and Stan the Eggman, “I’ll keep an eye on him next time he comes in.”

“He does it every time,” Stan says. “He does it every time!’

The first few times after that, when Coates comes in, I make a point of moving down the counter till I am right behind him, like a floorwalker in a department store. Coates knows I am standing there, even though he doesn’t turn around. I make it obvious that I am on to his game.

So this time, and maybe the next time, he only empties enough creamers to fill his cup once. Nothing wrong with putting cream in your coffee, is there? So he puts in as much as he can, with lots of sugar, taking a long time to do it, just to irritate me. When he has drawn it out as long as he can, he glides past me toward the door without saying a word.

I check the creamers. There are only two empties. He knows I am on to him.

It turns out he likes it better this way. It is more fun, it takes more skill, when the guy behind the counter is wise to you. It is an art, almost, stealing milk right in front of the cat.

And sure enough, the first time he comes in when I’m busy with customers, he goes to work. It only takes him about ten seconds, total, and if my attention is taken away for even half a minute while I have to pull out “this one, right here” for a guy pointing through the glass case at a specific jelly-filled doughnut way up in front where it is hard to reach, Coates leaves me four empty creamers and a mess on the counter for a bonus.

“Well,” he says, walking alongside the main counter so I can’t miss him, “Take it easy, now.”

I know that idiot grin is going to turn into a laugh the minute he gets outside the door.

♦

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

For five years in the mid-70s, I lived in an apartment above Kotzbeck Galleries at 2029 Fillmore. My neighborhood — in fact the entire known world, according to a guy named Chuck who played conga drums occasionally at Minnie’s — extended from Wilmot Alley to California Street. My shift at the Donut Hole was one afternoon a week, Friday, from 2 to 7. © James Brogan