By BARBARA KATE REPA

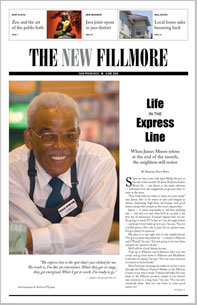

Some of the light will leave Mollie Stone’s at the end of the month. On June 30, 2009, James Calvin Moore Sr. — just James to his many admirers — will retire after 31 years at the neighborhood grocery store.

“Your body tells you when to retire, not your mind,” says James, who at 66 seems as spry and chipper as always, dispensing high-fives, fist-bumps and good humor along with receipts in the store’s express line.

James says he’s not sure what he’ll do in retirement. “I haven’t figured that out yet,” he says. “I’m not a hobby person. Not a fix-it man. I’m an opinion man. I’ve got plenty of opinions.”

He’ll definitely still be a local fixture, he says.

“I go up to Fillmore and California, then turn the corner and go back down to Fillmore and McAllister. I call that my square,” he says. “You can meet everyone you know in those blocks.”

James Moore came to San Francisco from Stephens, Arkansas, in 1962 looking for a job, drawn because his mother, Eunicetene, lived here. Now 83, she still lives in the neighborhood. Beyond that, he’s private about his personal life, allowing only that he’s had “a lot of wives and a lot of children.”

He got his first job cleaning meat counters at Westlake Shopping Center through a friend of the family and has stayed in the grocery business ever since, doing some of everything — working stock, unloading trucks, sweeping out the back room — and, for most of the last three decades, working at the checkstand.

“I always worked for a small company — no Safeway for me,” he says. “It’s more like family that way.”

After a stint with QFI, which was later acquired by Cala Foods, he came to the Grand Central Market on California near Fillmore in June 1978. “I was just lucky to be in the right place at the right time,” he says.

Rich Moresco, who owned the Grand Central before selling to Mollie Stone’s a decade ago, hired James. “It was the smartest thing I ever did,” Moresco says. “Jimmy’s always been a gentleman. He’s never had a bad word about anyone.” His former boss says James still gives him a gift every year on Father’s Day. “Every time I come in there, he can’t thank me enough for hiring him,” says Moresco. “He’s one in a million.”

“The store is it for me,” James says, “my customers, my family, my everything.”

Spend a few minutes with him on the street and it’s clear he knows everybody in the neighborhood. He keeps up a constant patter, calling out greetings to nearly every passerby.

“Good morning. You doing alright today?”

“You keeping busy this morning?

“Good morning, sweetheart, how you feeling today?” he says to an elderly woman on a walker, who looks up from the sidewalk and beams back, “Never better, sugar.”

But it’s inside Mollie Stone’s, in the express line — reserved at least theoretically for shoppers with fewer than a dozen items — where James has been a neighborhood fixture for as long as anyone can remember.

“That’s the spot that’s just clicked for me,” he says. “You hear a lot. You learn a lot. A lot of people come through there. And I just like people.”

“The truth is, I’m like an entertainer,” he says. “When they get on stage, they get energized. When I get to work, I’m just ready to go.”

He says he’ll still be a familiar face at Mollie Stone’s even after he retires. “I’ll be going there the rest of my life,” he says. “I have to mess with all those folks I worked with for so long. That will be the fun part.”

His longtime co-workers are not looking forward to his retirement, for several reasons. They all echo the sentiment that Lorain in the meat department expresses. “I’ll miss him, that’s for sure,” she says. “He always takes time out to help everyone else here.”

Also on the minds of his fellow cashiers is the concern they might have to take over the express line.

“I hate it,” says Nel, another longtime cashier. “People are supposed to be limited to 12 items or less, but they act like asses — loading up. Somehow, James is able to save the whole thing with his sense of humor. And he’s just so kind. He bought me my first discount Muni pass on my birthday when I became a senior. Now we laugh because he’s got one, too.”

Allen, who has checked at the registers alongside James for many years, still marvels at his cheerful disposition. “James always has a pleasant word for all the customers — even the grumpy ones,” he says. “We could all learn a lesson from that.”

“I don’t want a party,” James says as he enters his final month. “I’m too teary-eyed. I want to walk away quietly — just sort of ride into the sunset. It’s been beautiful to me — Grand Central, Mollie Stone’s. They were the best.”

He has just one request: “Don’t quit coming to Mollie Stone’s. I need my retirement check.”

THE REACTION: The news that James Moore would be retiring from Mollie Stone’s at the end of June 2009 prompted an unprecedented outpouring of sadness, nostalgia and just plain say-it’s-not-so.

All month long, people came by the store, some of them not to shop but just to wish him well. Many brought cards and gifts, which he stowed away on a shelf to be opened on his first official day of retirement. And all month long, James was able to bask in the glow of his many well-wishers. He even sent out copies of the June issue of the New Fillmore bearing his smiling photo on the front page to his entire Christmas card list — dozens of people including cousins, people from church and neighbors from his hometown of Stephens, Arkansas.

One was postmarked to his 8th grade teacher, Miss Hunt, who now lives in Los Angeles. “I called her up and told her: ‘Thanks for doing a good job,’ ” James says. “And she told me: ‘I can still see you now, trying to hide behind some other kid in class because you didn’t have your homework done. But I knew even then you weren’t a bad kid.’ ”

It wasn’t until the morning of his actual last day on the job that reality hit.

“It’s a different story today,” he said just before his final shift started as tears brimmed and fell from his eyes. “What do you do when you can’t go to work?” he asked. “You feel good — and you feel sad. But in the meantime, there’s something missing in your life.”

For all the accolades and urgings to stay, James had no second thoughts about leaving his post in the express line. “I might be looking good, but on the inside, it’s a different story,” he says. “You know, you see those old people at the drugstore buying that rubbing stuff. That’s me now — rub, rub, rub,” he says, cupping an aching knee. “And now that it’s my last day at the store, it’s going to be hard but it’s going to be good, and it’s . . . .” His voice chokes off as more tears come.

“One of these days, I’ll start laughing about this. But you can’t let time hold you back. And you have to really appreciate what you had,” he says. “I really appreciate what I had. I really appreciate it.”

SIDEBAR: “How’s your mother?”

REACTION: “The meaning of life”

UPDATE: “Life after the express line“