By RONALD HOBBS

Watering at the same well

Big butterfly paint-lipped Ruth Dewson was a lost soul in a sleek red Cadillac. She did nails and eyebrows before she got into hats. Hats made her famous.

We used to water at the same well, the Pacific Heights Bar & Grill, after work. That place was the neighborhood bar, but not one of your yahoo show-your-ass joints. It was real. It had the odor of privilege, but it didn’t stink. And it was home-like.

Ruth often excused herself to the ladies room, leaving her checkbook open. And I or one person or another who was sitting at hand could see the check stubs written to “Friends of the Committee for (name your politician).”

She was a large and voluptuous woman — fun and funny — and a conniving bitch. A little girl wanting to be grown up. She wanted to prove something to Paris, Texas, her home town. But mostly she wanted to prove something to herself.

So interesting, this business of being alive!

A measure of sincerity

The place was jammed, the Pacific Heights Bar & Grill. We had just come from St. Dominic’s after listening to Mother Teresa speak of terrible sufferings in Calcutta. During the offertory, the long-armed baskets heaped with the long green. And in those days there was the “AIDS thing” going on. But it was most likely guilt, not conscience, that stuffed the coffers.

I suppose it did not matter, for money is a measure of sincerity.

At the time I was not well fixed, and practicality has never been my long suit. But I was walking in a $200 pair of shoes and wearing a $50 necktie. And now I had an $8 glass of Cabernet sitting in front of me. A half-dozen oysters would run me that twice. Of the gathered crowd I was one of the minnows. If I sipped slowly, I could ride this for another couple of hours.

The crowd thinned at about 10 and I cashed out with a generous tip, about the same I put into the long arm of guilt. I left with $6. Pathetic, I know. But I wanted to see it through. I hung my clothes not so neatly. I was drunk in some indefinable way, not the .08% way.

I did not fully believe Mother Teresa, my shoes, the oysters, the necktie. And I didn’t give a shit about lepers or orphans in Calcutta. I lit a cigarette and turned on the 10 o’clock news.

It was Harry’s Bar

I enjoyed very much Harry Denton. He was a whiskey-throated, cigarette sucking, homosexual fat boy drunkard charmer. This is not gossip, it is a story he himself has not only told but capitalized on.

He had assumed the lease on Nate Thurmond’s defunct restaurant on Fillmore Street when we met. Harry was having a tough time of things in those days. Morning after morning I would see his junky yellow Mazda pickup truck parked in front of the storefront.

But his popularity extended into the Nob Hill Gazette crowd, and Herb Caen, an important columnist, often said, and meant to say, great things about Harry. Harry was great copy that had San Francisco scribbled all over it!

When Harry’s Bar opened on Fillmore there were lines, and then longer and longer lines. Harry’s wallet swelled with May!

More than once, late near closing, Harry would drop trou and dance in his shorts on the bar. Three hundred pounds of a fat man in tighty-whities atop a bar making a room shake like a 6.1 on the Richter scale was a real experience!

His fame, his flame, flourished though, and after he cashed out his bar for the last call, he wound up at the Starlight Room at the Sir Francis Drake Hotel at Union Square.

Oh that was grander in spades! But instead of the few minutes we used to spend together at greeting, I now got a quick hug, 20 seconds of the old days, tops, and a free drink.

I understood. I was happy for him. And I was not unknown either to the staff or the house, excepting the scads of tourists. I still had a little bit of currency left in that world.

But even all that is water passed over the dam now. I haven’t seen Harry in years; his name isn’t in the papers anymore. Maybe it is a case of “to everything, turn… turn… turn…”

At the Donut Hole

Aunt Beebee, Bertha, and I were no kin at all. She was “that nice old colored woman” who worked at the Donut Hole. Her niece, Bettye, called her Aunt Beebee. It caught on with us regulars. The joint must have served 500 cups of joe a day and a couple of thousand donuts. But for all of the in-and-outers, only a few of us knew her secret name.

Bettye was 300 pounds of a scorched-tongued negress who worked graveyard. There was no need for a bouncer at the Donut Hole on her shift. Besides, in the back room the bakers, Buck and Chuck, packed some serious heat.

We came bleary-eyed and loud after the clubs closed. It was sugar time. Sugar and caffeine not so discretely spiked with Korbel brandy. Bettye fussed over us like we were her own children, as if we were the little crosses, cable cars and bridges on her charm bracelet.

Aunt Beebee came on at 6, and after her soon followed the morning people. The newspaper readers and the cigarette smokers and the shift-changers throughout the city. Aunt Beebee wasn’t a small woman, either, but she was a willow next to Bettye. I’ve seen love before; I’ve seen deception and bloody skulls on sidewalks — but I never saw a love like this one between the two of them. They even fussed at each other with love.

“Where’s the napkins at?”

“Find ’em your own fuckin’ self, I’m outta here old lady!”

“Who you calling old lady, Miss Fat Ass! You coming for Earl’s gumbo tonight?”

“I made a sweet potato pie, what time, bitch?”

On one of those long weekend holidays — it was about 4 in the afternoon — there was nobody but me and Aunt Beebee in the Donut Hole. She brought over an apple fritter, broke it in half and we sat there together twisting off nibbles and licking the sugar off our fingers.

“Know what I believe?” Beebee more said than asked. “I b’leeve like the Jehovah Witness people, you got to call God by his right name or he can’t hear a word you’re saying. I’ve tried. I even sent a $5 seed of faith to Reverend Ike. It’s been two weeks now and I ain’t seen a goddamned nickel!”

Outside, old Mr. Jessee had just put his ’62 Impala in park and turned off the key. The old junker chug-a-chugged until it died. Now we were three people picking at an apple fritter and licking our fingers.

“Mr. Jessee,” I asked, “if the Lord needed $20 would you give it him?”

“Hell’s bells, if the Lord needed 20, I’d give him 40, no questions asked!”

“He needs it, Mr. Jessee. Put the money in my hand and He will show you not one, but three miracles, three blessings in real time. Someone has planted a seed of faith and you have been chosen to raise that seed up and bring it to blossom.”

Mr. Jessee suffered over that. He squinched up his eyes and made a funny mouth, he scratched his nappy hair. He wiped the crumbs of sugar on his pants. Then he reached into his pocket and gave me $40. I wadded the bills up into a little ball and held it to Aunt Beebee’s open hand. “Jehovah God!” she shouted. “Thank you, Jesus! Hallelujah!”

Mr. Jessee shook his head. “You never know. You just never know how you might be a part of the mysterious workin’s of the Lord — and this be mighty damned mysterious!”

Minnie’s Can-Do Club

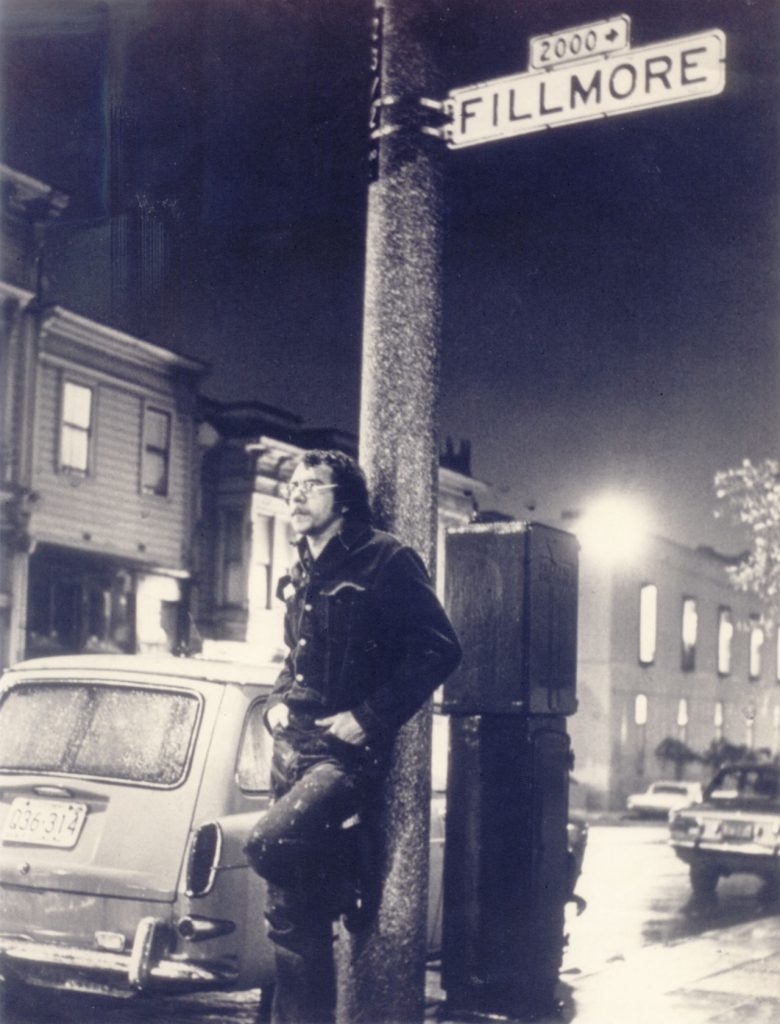

As I recollect, I arrived in San Francisco on September 1, 1970. I met Minnie Baker six months later. I walked into the Can-Do Club because there wasn’t any acceptable bar on Fillmore. There was the Hillcrest, which wasn’t acceptable. It was a good drinking bar, but I didn’t meet the kind of people I enjoyed. The Hideaway was alright, but it was a little older and it was just ‘salt and pepper,’ which wasn’t good enough somehow at the time. I walked into Minnie’s and she asked my name and that was the beginning of a long and stormy romance. Romance in a generic sense, mind you.

And then, see, I was keeping shop and my shop wasn’t really doing good and I ran up a bar bill and I couldn’t pay. I had a small coffee shop here on Pine and Fillmore. I sold imported coffees and body lotions and stuff like that under my own label. The shop was way ahead of its time. And in order for Minnie to get her money back, she thought she had to hire me. I was the bartender. Everybody knew Sunshein, my street name. I started keeping the bar with Aaron, Minnie’s son, and Felita, Minnie’s daughter.

The ambiance of course made it special, but you can’t use words like ambiance for a bar that was terrifying to look at, in some respects. Silver all over the walls. It was a multi-cultural place in a very true sense. At that time we had 25 to 30 Japanese kids living in a commune up the street. The commune was called Konyaku, which in Japanese means noodle. They were artists and many of those artists established international reputations at galleries in London, Paris and Tokyo.

At that time, Mr. Takahashi was around. He was a Samurai and wore the traditional clothing and carried a sword. He carried his own record of his genealogy from Japan, which named his father and his father’s father and all the fathers before him who were Samurai. Mr. Takahashi spoke very little English, but he owned one of the most beautiful art galleries in the Japan Center, which was near the Can-Do. Occasionally Mr. Takahashi came in for a beer while I was bartending. On one particular occasion, a young, strapping man started making jibes at Mr. Takahashi and making fun of his “dress.” In a couple of moments this young man became vociferous and challenging . . . at which point Mr. Takahashi smiled and bowed and walked to the dance floor and removed his sword from its sheath. After about three minutes of expert swordsman’s demonstration, Mr. Takahashi bowed and put the sword back in its sheath. He came back and sat down at the same bar stool. The young man left hastily.

Blacks and whites came in, and we had some Apaches on occasion. It was a people’s bar and exchange center. It was a place you could touch and get money and pay them back or maybe not. The music was great and Minnie was Minnie’s Can-Do. Everyday my friend Alice Murdock and I would go there. There were straight people and gay people and upside down people. Richard Hongisto, who was the sheriff at the time, was a regular there. Cops on the street were congenial.

About that time, 1972 or ’73, there was local opposition to Minnie being granted a cabaret license, which would mean she could have live music. So 30 of us loaded up in cars and trucks to go to the permit board for her to get her license. I think a few locals were afraid of the loud music and rip-off that they felt had to ensue. But the rip-off didn’t ensue. Minnie got the license.

There was a ping pong table, so at lunch time a lot of the fellows from the telephone company would come. The bar attracted a log of young French people from the local French newspaper.

I started the poetry readings. I think we started in ’72. Minnie and I were talking one particularly slow night and I said, “Let’s have a poetry reading one night a week.”

“It’ll never work,” she replied.

We looked at each other and both of us said at the same time, “Fine, let’s do it.”

I remember the first two or three nights of the poetry readings. I was a little brassier then than I am now, and I would go to the bar and tell people to shut up. But then folks got into it in a big way. At Christmas we had poem trees where the poets would come from all over the city to hang their poems written on a piece of paper on the tree, and we would read them. Like a Christmas tree, the poems were alive for that moment.

After about nine months I turned the poetry over to ruth weiss, an important American poet. ruth and I worked hand in hand and then when ruth got tired of it, Max Schwartz and Charles Storey took it over. We had a three year anniversary party of the poetry readings. The anniversary party was typical of most of the readings. It was wall to wall people and you had to climb over them to get to the bathrooms.

My first Thanksgiving in San Francisco I had with Minnie, her mother and her son and daughter. We ate at Connie’s West Indian restaurant on Fillmore between Pine and Bush. Fillmore Street was really alive then. This area from California to Sutter was sort of a DMZ. Blacks and whites mingled, but it was touch and go except at Minnie’s.

SunDance magazine came on the scene and one day there were some people from the magazine in Minnie’s. I was there, just sitting and listening to the jukebox. Minnie was getting excited and she called me over and she said, “I have some people here that I want you to meet.” I said, “Oh?” And she said, “This is John and this is Yoko,” and I said, “Hello, very nice to meet you.” They replied in kind and I went back and sat down and continued to listen to the jukebox and drink my beer. And that was the one and only time I met John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

One night Minnie and I were in our cups and she said, “Sunshein, get my piece and put it in my purse. Come with me. You’re going to have a Black Studies program.” When Minnie Baker goes out, she doesn’t allow no motherfucker to mess with her. So we went out that night to a lot of clubs in the Fillmore that were still very colorful and it wouldn’t be good for a honky to go in alone. I got to see a different life than I’d seen before.