GARDENS | JOAN HOCKADAY

The cow is gone, the windmill torn down, the pharmacy delivery trucks missing from the garage behind the house. The gas pump and the water well no longer pump at all. But some reminders of the storied past of the historic Shumate house and garden at the corner of Pine and Scott remain — including the cobblestones.

Unearthing hidden cobblestones in any San Francisco garden is an instant reminder of the city’s Gold Rush days, when ships with cobblestones used as ballast sat in the harbor after sailors rushed for the gold fields. The heavy stones weighted down the ships during long voyages west, but after 1849 the ships — and the wood and the cobbles — were there for the taking.

After the city took its share to pave dusty or muddy streets, the abandoned stones were commandeered by treasure hunters of a different sort — and now adorn gardens around San Francisco, a link to the early days of the rush to gold.

One of the city’s oldest and largest gardens harbored just such a stash of stones when new owners purchased 1901 Scott Street in 1999. Fifteen years after moving in, they have kept the cobbles and the best of the old while adding modern essentials — and opening the house to the south-facing garden.

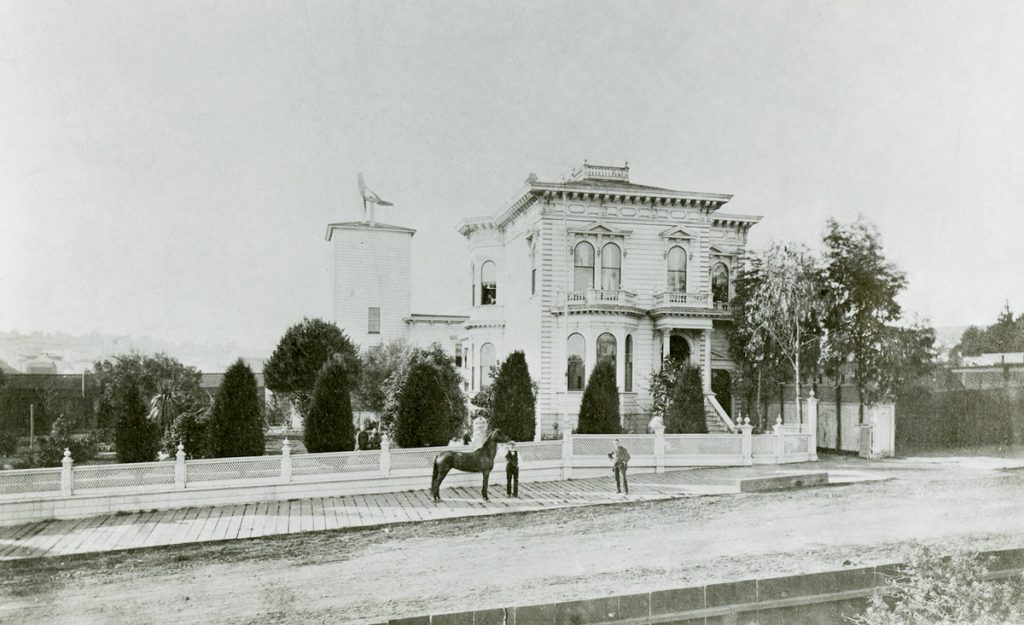

Built in 1870 and recorded as San Francisco landmark number 98, the Ortman-Shumate house and its expansive garden at 1901 Scott Street was a family compound for three generations, until Dr. Albert Shumate’s death in 1998 at age 93.

But after nearly 130 years, the house needed repair, the neglected garden needed care — and the Landmarks Board needed to weigh in on any changes to the historic facade set amidst one of the city’s largest private gardens.

“It was a throwback to old San Francisco,” said new owner Peter Wald. “The property was not in good shape” and the grounds were “not touched” for a while.

After consulting San Francisco Heritage — headquartered in the historic Haas-Lilienthal house on Franklin — and then petitioning the San Francisco Landmarks Board for approval of the many plans required for restoration, the owners finally moved in a year after purchasing the property, with their “certificate of appropriateness” from the city.

First, the house received an overhaul. Rotting wood, broken gates and peeling paint received immediate attention before structural changes brought the house up to contemporary standards.

“We wanted to preserve the spectacular tranquility” of the site, Wald says, explaining the decision to complete renovations on the house before making over the garden.

Six years later, the garden finally became the focus, as architect and landscape architects took a long hard look outside once the contractors were through with the main house.

The owners and their advisors were concerned by the lack of direct entry to the garden. While the garden was a showpiece of tall trees and steep terrain, the house only looked out on it. After a sweeping staircase was added to link the house to the garden, the neglected garden was then transformed. The sloping north-to-south lot was broken into three separate square patio areas and the long east-west curves of the previous design discarded for smaller, more intimate “garden rooms” — two alongside the house and the third near the remodeled carriage house in the back.

Landscape architect Scott Lewis ordered bluestone paving for the upper patio closest to the staircase and house. Bluestone, Lewis says, won’t crack in San Francisco as it does in hotter interior gardens. He notes that the color of the East Coast stone blends into the landscape, and the flagstone cuts give the appearance of permanence upon reaching the garden from the house.

Stone also edges each garden room, while a matching hard surface covers the garage entry and basketball court beyond the house. Basketball for two growing children is given plenty of space, separated from the main garden by a row of one of the owners’ favorite trees, flowering cherry. A cultivated variety holds up well to basketball out-of-bounds shots and to changing San Francisco weather.

The lawn area is greatly reduced in size from its original configuration, as in many San Francisco gardens this past decade. Instead, massed hedging now surrounds the old lawn and two new outdoor spaces were created. Stone steps now separate the steeper portions of the garden, giving the entire space a more intimate and less daunting feel.

Little side gardens tucked under and near the historic trees on the Scott Street side finish the south garden overhaul. A ginkgo tree is in a western-facing sun spot of the garden, with an attendant buddha beneath.

The old yew trees, once thought too feeble to keep, are still wedged along the property line, pruned back hard to keep their shape, and providing an essential buffer to the constant traffic on the Pine Street side. A row of yews and masses of greenery packed between the street and garden help to reduce traffic noise.

The outer garden walls were repaired and raised to better reflect the slope down to Pine Street and, surrounded by greens, now show the north-south incline. Camellias mixed with roses (in the sun) and hydrangeas (in the shade) round out the eastern edge of the garden, which is dominated by a splendid Norfolk Island pine, a landmark to neighbors and passersby. Landscape architect Scott Lewis advised keeping the pine and other older trees, but lifting the overhanging fronds up off the ground to allow in light and air.

Finding a gardener to keep the renovated garden in shape was almost more daunting than the overhaul itself. And so these modern owners took the modern approach by checking online and on social media for gardeners with high marks. To their surprise, one of the most highly recommended gardeners worked only in Marin. The owners, both lawyers, decided to plead their case. They won, and the Marin gardener — who shall remain anonymous, as is traditional when a good gardener is finally found — now comes to the city to help keep the new garden ship-shape.

The gardener also maintains the handsome side street garden that runs along Scott Street beside the house and along the school playground next door on property that was also once owned by the Shumate family. By keeping a garden beyond the private space, and blending the greenery up the street, a softer edge is created between the house and the schoolyard.

A taller unobtrusive fence between the school and the house is the final touch to give privacy and history a soft link. Still, from the street and the house, the last big Canary Island date palm is still visible in the playground and a reminder of early days in San Francisco when property west of Fillmore was open and full of places to picnic.

Gardeners say it takes seven years to adjust to a new garden, to know each corner and its soil and sun and fog and wind, to see the results of early plantings, to make little changes, to tuck favorites into the right places. With the passage of time, and the careful observations of the new owners through each season in San Francisco, this old garden has new life.

Joan Hockaday is the author of The Gardens of San Francisco, published by Timber Press.

FROM THE ARCHIVES: “Shumate’s Pharmacies“

A GARDEN OF TREES FROM AROUND THE WORLD

When architects, landscape architects and the new property owners finally sat down — six years after they began renovating the Shumate house — to take a long view of the old garden, they never gave a thought to cutting down the massive Norfolk Island pine tree in the south garden.

“Never,” says architect Lewis Butler. “It has to be one of the tallest in the city. You can see it from the crest of the hill a mile away.”

Judging from historic photos in the California Historical Society’s archives — Dr. Albert Shumate was president of the society in the 1960s — this tree might be one of the oldest in the city. It was planted not long after the house and garden were established in 1870.

The Norfolk Island pine, from the South Pacific, is a fabled San Francisco tree. Introduced into the city in 1859 by South Park nurseryman William Connell Walker at his Golden Gate Nursery, these long-lived trees all started as little potted plants.

The date palm of the Canary Islands was introduced into California in the late 1800s, but the romantic notion endures that the mission padres brought these trees along the trail south to north a century earlier.

Preserved now in the historic Shumate garden is at least one handsome early San Francisco palm, with another standing tall in the schoolyard next door, which was also once a portion of the family compound. For decades fronds were gathered from these trees for Palm Sunday services at nearby St. Dominic’s Church, where the Shumate family worshiped.

The newest tree planted in the old Shumate garden will probably outlast all the others. A young ginkgo tree — a favorite of the new owners — will, if ancient Asian origins hold, survive renovations, car exhaust and foggy days for at least a thousand years. The buddha below the tree emphasizes its importance to Asian cultures.

— Joan Hockaday

Filed under: Home & Garden, Neighborhood History