A HANDSOME NEW BOOK — melodiously titled A Dream Begun So Long Ago — chronicles the life of photographer David Johnson from his childhood, shuffling through the care of various adults in segregated Jacksonville, Florida, through his on-and-off relationship with the art of photography. Now it’s firmly on again as the 86-year-old relishes his recognition as one of the foremost historical chroniclers of black life in San Francisco and the Fillmore community in particular.

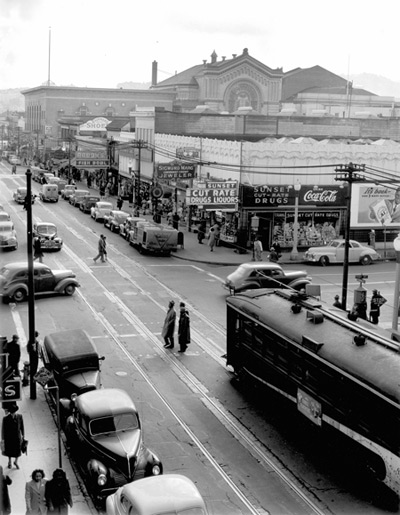

In the book, told in the first person and written with his wife Jacqueline Annette Sue, Johnson reminisces about his early days under the tutelage of Ansel Adams — and the day in 1946 he climbed up on a scaffold to take what would become an iconic photograph of the neighborhood called Looking South on Fillmore. Excerpts from the book follow.

I work in the darkroom alongside Ansel Adams as he produces very large black and white landscape murals. As I watch him working, we have a conversation about print quality as he applies some developer to a print. I say laughingly, “I thought you were a purist,” meaning showing the photograph just as it was taken. Ansel chuckles and says, “Yes, but I am not an absolute purist.”

I know nothing about nature and I am not interested in still life. So my mentors tell me to take photographs of the things and people I see that interest me. One day, I take my camera, light meter and tripod and climb a building scaffold. Setting up my equipment about four stories up, perching precariously on an unstable landing, I take a photograph that will, 50 years later, become an historical San Francisco street scene. Set in black and white, looking down Post and Fillmore Streets, the photograph sets in time the Number 22 Fillmore streetcar, vintage automobiles, people crossing the street and the future Fillmore auditorium.

Johnson recalls renting an apartment for $75 a month in the early ’50s at 1818 Divisadero Street that included a small storefront space, allowing him to realize his dream of opening his own business: Johnson Photography Studio.

However, no way can I support a family taking pictures. I have to keep my day job at the post office. To keep up my photography interests, I establish a business exchange contract with the Sun Reporter newspaper.

The Sun Reporter assignments give me access to photograph important San Francisco community leaders like Congressman Philip Burton, future supervisor Terry Francois and Reverend Hamilton T. Boswell.

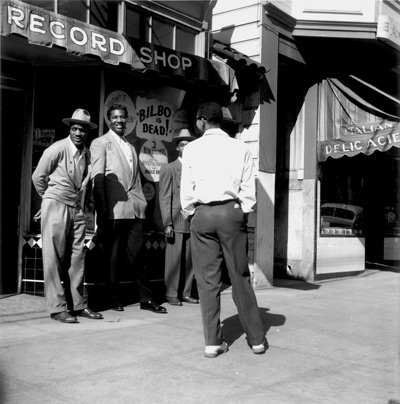

This is how I begin to photograph many of the men and women who are to become notable figures in the American historical milieu. I continue to take pictures of life in the Fillmore. The jazz scene with the visiting musicians at the Primalon Ballroom, the Booker T. Washington Hotel, the Texas Playhouse, the New Orleans Swing Club and the Flamingo Club are my favorite places to capture the nightlife of the city. I take my twin-lens reflex film camera and photograph the musicians and singers as they perform. In the ’40s and ’50s, the Fillmore District was the hot spot in San Francisco where entertainers came to “jam.”

I work at the post office during the years when the unions are becoming strong enough to represent employees in collective bargaining. In the 1950s and ’60s, minorities and women are excluded from many jobs in the post office workforce. In order to seek out equal opportunity not only for myself but also my friends and others, I join a union and am elected president of the local chapter of the National Alliance of Postal Employees. Working a full-time job and negotiating employee grievances leaves me little or no time to take photographs, so I make the decision to close the Johnson Photography Studio and move my family out of the storefront and back to the Bayview district.

By 1999 Johnson was back in Florida, living in Miami and working with the state’s foster care agency. He was on hiatus from photography when he and a friend hatched a plan to visit Cuba with the aim of “jumpstarting his return to the art of photography.”

Arriving in Havana and getting settled is fairly simple. Miami friends from Cuba recommended that we stay in a nice little hotel located in the central part of the city. The rate for the hotel is very reasonable: $100 per night for a room with twin beds. I bring my Nikon camera to Cuba with me. This trip is a rejuvenation of my photographic years in the San Francisco Fillmore District.

Sunday morning is a bright, beautiful Cuban day. I wake up early, and without my friend Arthur, walk to the Plaza de la Revolucion. I take a self tour of the neighborhood. People are out sitting on the sidewalks. Much of the city to me appears to be a relic of its past history. I take photographs of crumbling buildings and old electric wires drooping from their poles onto the streets. I spy a couple and photograph them, and then I take a picture of boys playing in an old fountain in a nearby square.

During the mid-day, as is the Cuban tradition, I return to the hotel and take a nap. In the evening, Arthur and I have dinner and visit a nightclub in a house. I photograph the musicians and other guests, just like I did in the Jazz Age of the Fillmore.

In the years just after 2000, events converged to prompt Johnson to move from Miami and return to San Francisco: his longing to spend time with his growing children, who lived here, a diagnosis of prostate cancer — and especially the local public television station KQED’s decision to do a series about the Fillmore District.

The KQED TV special on the Fillmore uses 17 of my photographs and begins the renaissance of my photographic exhibit career. (A couple of years later, producer Liz Pepin and Lew Watts will co-write a book, Harlem of the West, that will feature many of my jazz photographs.)

My return to San Francisco coincides with the revitalization of the Fillmore District. Authors begin to write about the Jazz Era, the landmarks that were once familiar and the photographs of the 1940s and 1950s. The pictures I took as a student of Ansel Adams are now considered “art.” Galleries, museums and print media are now interested in my work.

One day when we are walking down the renovated Fillmore Street, we pass the Gene Suttle Plaza and discover my name engraved in the sidewalk.

DAVID JOHNSON

Photographer and Photo Journalist

Studied under Ansel Adams

A dream begun so long ago is coming true, and I am beginning to be recognized for my work.

EARLIER: “From old Fillmore photos, a rebirth“

Filed under: Art & Design, Books, Locals, Neighborhood History