FILM | Barbara Kate Repa

JIM TRACY, longtime running coach at the neighborhood’s University High School, never set out to be a film star. But when life conspired to deliver a record-setting team, a diagnosis of Lou Gehrig’s Disease and a community that rallied around it all, he could be no other.

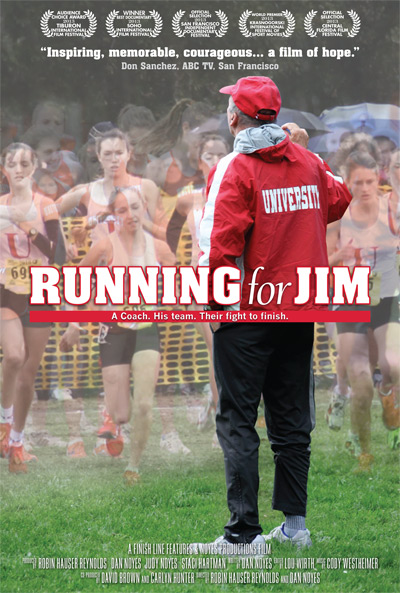

The result is Running for Jim, which screens this month at the San Francisco Independent Documentary Film Festival.

One race in particular provided the dramatic high point of the film. The University High School girls’ cross country team, having recently learned their beloved coach had been diagnosed with the fatal disease, was set to compete in the 2010 state championship, a 3.1-mile race run on a cold damp day in Fresno. Team captain Holland Reynolds gathered the team for the usual rallying cheer: “Go Big Red! Go Devils!” Then they added, more like a prayer, “Let’s do it for Jim.”

The race was a nail-biter from the start. One of the team’s top runners, Jennie Callan, fell at the 100-yard mark and slipped to last place, then rallied to finish 16th in the roster of 169 runners. Other team members also ran their hearts out. Adrian Kerester, who had never run in a state final meet, placed 25th. Lizzie Teerlink beat her personal best time. Bridget Blum led for more than half the race, finishing third.

But Holland Reynolds, the team’s fastest runner, slowed around the 2.5 mile mark, then hit the wall. Three yards from the finish line, dazed and dehydrated, she collapsed and fell to the ground. A race official hovered over her, explaining she either had to complete the race without help or withdraw. An agonizing 20 seconds of film shows Reynolds crawling over the finish line before being swept away to a waiting ambulance.

Her explanation: “Of course I was going to finish. I just knew I needed to do it for Jim because we needed to win state for Jim.”

Holland’s mother, photographer Robin Hauser Reynolds, was taking pictures at the race.

“I saw her on the ground and our eyes locked, and at that minute I knew she would be okay,” she says. “It was actually a disappointing day for her and the rest of us, because she expected to finish second — and didn’t.”

But the film clip of Reynolds’ spectacular finish quickly went viral. New York Giants coach Tom Coughlin played it repeatedly to inspire his team to win the Super Bowl; his plea for his team to “finish the job” became synonymous with the image of Holland completing the race.

It is the stuff of which movies are made — and filmmakers soon swooped in. But the close-knit group of key players feared an outsider might misdirect the focus away from their coach and the need for research on his disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, popularly known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease. So Hauser Reynolds took over the film project and turned to the community for help. She brought in ABC news reporter Dan Noyes to write the narrative; his wife, video expert Judy Noyes, whose father died of ALS, is a producer, as is neighborhood resident Staci Hartman, who helped with production and distribution.

Jim Tracy, by then suffering the debilitating effects of the disease, trusted the film team enough to allow them to trail him for two years, recording intimate moments with visiting family members, workouts with physical therapists, consultations with Dr. Robert Miller at nearby California Pacific Medical Center — and his ongoing work coaching his teams.

The result, Running for Jim, is a 78-minute documentary. The film, which had its world premiere in Moscow in April, has already snagged impressive accolades at film festivals, including the Best Documentary Award at the Soho International Film Festival and the Audience Choice Award at the Tiburon International Film Festival. The creators hope to finalize a distributorship deal this month, ensuring that all net proceeds go to ALS charities.

Jim tracy developed a reverence for running at a young age, when his family worked in horse racing. Sleeping in horse trailers during the summers while they followed the racing circuit up and down the California coast, he and his siblings would practice by bursting out of the starting gates, then racing barefoot around the track. Jim would usually win, especially if it was a long-distance race.

When he got to San Francisco’s Archbishop Riordan High School, he joined the cross country team and quickly established himself as a superstar.

“I could actually win — actually be popular,” he says. “And that’s stayed with me. Kids ought to be involved in something they can achieve, where someone else can recognize them. I think that’s so important.”

After graduating from college in 1973 — the first year schools were mandated to have sports programs for girls, he notes — Tracy held a number of odd jobs. The worst of them was in the Merchant Marine as a “wiper” assigned to wipe up oil spills and other messes aboard ship.

“It sounds bad, and it is bad,” Tracy says now. “It was always more fun to run than to work.”

Then in 1994, a friend enticed him with a job that sounded to Tracy like pure fun: coaching track and cross country at the neighborhood’s University High School, on Washington Street near Lyon.

While the coach developed close relationships with his young charges, he told them little about his personal life. Rumors swirled that he lived in his car. And those rumors were true. Shunning material goods, Tracy says he did sometimes live in his car between stints as a house sitter. He lived to run and coach, and little else mattered.

The disease weakened him so much that eventually he could no longer run. Now he can’t walk, either, and gets about in a motorized wheelchair. But Tracy still earns honors for his coaching; in May, he was inducted in the San Francisco Prep School Hall of Fame.

Tracy remains close to his family: a sister and brother — and especially his 90-year-old mother, Dee Tracy.

In the film, his mother recalls her initial reaction to Jim’s diagnosis: “I couldn’t believe it. He was the healthiest person in the world.”

The disease first made the news in 1939, when famed baseball player Lou Gehrig was diagnosed with it, and ALS became popularly known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease. In Running for Jim, the coach is shown watching a newsreel of Gehrig announcing his retirement from baseball at age 36. Tears well up in both of them as Gehrig concludes: “I might have been given a bad break, but I’ve got an awful lot to live for.”

That’s vintage Jim Tracy, too: upbeat, forward-thinking and realistic.

“Soon I’ll have the summer off,” he said recently. “And if I have the strength, I will be the cross country coach next September. It will be my 20th season at University.”

Tracy’s symptoms first surfaced as a pesky numbness in his right hand, along with an even more annoying weakness that caused his foot to flop against the pavement during his daily 10-mile runs up and down San Francisco’s hills. In 2010, at age 60, Tracy was diagnosed with ALS, which attacks nerve cells and pathways in the brain and spinal cord. The disease is progressive, degenerative and ultimately fatal.

“I got the diagnosis over three years ago,” Tracy says. “I described all my symptoms and the doctor said, ‘We’re certain that’s it. You have ALS.’ And I thought to myself, ‘There are bad things you get. They give you medicine and put you on a treatment program.’ Then the doctor said to me, ‘By the way, there is no medicine and no treatment.’ ”

By most medical counts, Tracy has a slower-acting form of the disease. The prognosis is two to five years from the time of diagnosis.

“It’s such a quick disease — it can come on and take people in just two or three years,” Tracy says. “Since I’ve become ill, I’ve met some people who are much worse off than I am. I’ve met people who have been cheated out of their last comfortable moments.” He adds: “The disease takes all your energy, then your voice. Eventually you can’t move and you can’t speak.”

Tracy and others involved in making the documentary hope it will help focus attention on ALS research and change misconceptions about the disease. Foremost, they say, it’s often considered an “old person’s disease,” shrugged off as part of the aging process. In fact, 30 percent of those diagnosed are 30 or younger. And the debilitating disease is more common than most people imagine: About 30,000 Americans are now living with the diagnosis.

“It’s still a situation where not nearly enough money and not nearly enough sharp people are attacking it,” Tracy says. “Quite frankly, we don’t have that combination working yet.” But his advice for others with ALS is a characteristic combination of optimism and realism. “Stay very much involved with everything you can do while you can do it,” he says. “And fully expect to get worse.”

Tracy is often credited with building a running dynasty at University High — a description that’s hard to resist for the winningest high school cross country coach in California history. But despite the many honors bestowed upon him, the humble Tracy would be the last to claim the honor.

Running for Jim includes footage of the coach in action with his athletes: cheering them on from the sidelines, inspiring them at team meetings, joking with them in the stands after practice and egging them on as they circle the track — always using Tracyisms that combine humor, unrelenting tough love and caring support.

“Come on now — this is a stopwatch, not a sundial!”

“This is real training, not pretend time!”

“Get to that finish line. You want to get there. Get there! Get there quicker!”

And the mantra all team members can quote chapter and verse: “We train farther than we race, so the race seems short; and we train faster than we race, so the race seems easy.”

The parents of those he coaches are especially grateful.

“His passion to teach kids to run is what sets him apart,” says Hauser Reynolds. “And it’s not necessarily the gifted runners. He really gets pride and joy from those who just become faster and better runners, in seeing them improve and gain self-confidence.”

Tracy’s diagnosis has also helped the athletes learn a powerful life lesson.

“Dealing with a coach they love who is diagnosed with a fatal disease forced the whole team to break out of their insular teenage minds and made them appreciate their own health and their own lives,” she says. “It’s given them a greater perspective on life.”

His athletes gave their all, but the entire school community rallied after Tracy’s diagnosis. School officials set up a fund to help cover his living expenses and rented a specially equipped apartment in the Presidio, just five minutes from school. The athletic department helped solicit donations and furnishings.

“Everyone went through their homes looking for things to donate,” says Robin Hauser Reynolds. “It was another lesson that Jim taught the kids: They saw how much we really have.”

Hundreds of items were donated, ranging from a serving spoon to a couch.

A team of University High students, paid for their Sunday labors in cheesesteaks, loaded a truck and moved the items into Tracy’s new apartment.

As Tracy inspects his new digs, the film captures his disbelief. “I’ve never owned a couch in my life. Not one. This is my first couch — and it’s comfy,” he says. “I’ve never had as nice a place as this in my life.”

Reflecting now, Tracy finds his new apartment a perfect fit. “It’s good for me as long as I maintain a certain amount of mobility, as long as I don’t need someone to watch me constantly. And I still have my voice, so I can call for help,” he says. “People have been so generous and helpful. With this disease, you have to put yourself in other people’s hands, and I never had to do that before because I was self-sufficient.”

He says he’s buoyed by the outpouring of support from the school, the community and his family, especially his mother.

“My mother just celebrated her 90th birthday. She has a great attitude about all she’s accomplished in life,” he says with some pride. “I feel if your parents are optimistic, you have a better chance at being optimistic, too. And she has good stories to tell. Now I say, ‘I’m a story to tell, too’ — and I hope someone will listen.”

As part of the 2013 San Francisco Independent Documentary Film Festival, Running for Jim will be screened on June 7 at the Balboa Theater and on June 9 and 10 at the Roxie Theater. Tickets and showtimes.

WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM HIS FRIENDS

Dedicated to running and his athletes, Coach Jim Tracy has always lived frugally, with few funds to spare for treating a complicated medical condition. So in 2010, the University High School faculty set up a trust to help cover Tracy’s living expenses — primarily his rent and utilities.

About $50,000 was raised when the trust was initially established, with donations mostly from friends and UHS parents and faculty, plus some from as far away as Alaska and Alabama. But that amount has now dwindled, according to University High School business manager Sue Davenport, one of the trustees who manages the funds.

Like so many others involved in the cause, Davenport says she feels she has a personal stake because Tracy has touched her life.

“Adolescence is tough for a lot of kids,” she says. “But Jim is amazing — and has changed so many kids’ lives by virtue of his coaching skills and great attitude, teaching them to have a broad focus beyond academics, to pursue excellence on some level.” One of his students was Davenport’s daughter; Tracy was her coach when she ran track at University High.

“What strikes me about him is his humility and genuineness, the simple direct way he faces everyone’s potential — including his own,” Davenport says. “And he has such a sense of humor. If my daughter had a crummy race, he’d say to her: ‘That might not be one of the best times you’ve had, but at least you got a good workout.’ ” Davenport’s daughter, now 24 years old, still loves to run.

For more information about the trust, contact Sue Davenport at 415-447-3103 or visit this website. Checks can also be sent to the Jim Tracy Special Needs Trust at University High School, 3065 Washington Street, San Francisco, CA 94115.