LOCAL HISTORY | PEGGY ZEIGLER

As San Francisco celebrates the 100th anniversary of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, the dome of the Palace of Fine Arts is decked out in new paint and the Ferry Building is illuminated as it was in 1915. Re-creations of the expo grounds flash in the windows of the California Historical Society announcing its exhibition of City Rising: San Francisco and the 1915 World’s Fair.

But the neighborhood connection to the exposition — that of the Fillmore Tunnel — is yet to be told. For that we must look back more than a century, to the fall of 1911.

It was then that the San Francisco Board of Supervisors hired Bion J. Arnold to make an impartial assessment of the city’s transportation system. Arnold saw at once that the hills and ridges divided the city into districts. And his studies revealed that the western third of the city was underdeveloped simply because of the excessive time it took to commute to the downtown area.

But Arnold had a plan. He firmly believed that these barriers could be removed by constructing tunnels through many of the intervening hills.

Tunnels quickly became the name of the game. The Board of Supervisors established a Tunnel Committee, as did San Francisco’s active Civic League of Improvement Clubs. A plan for a tunnel through the Stockton hill was approved. The Golden Gate Improvement Association submitted a resolution to the Board of Supervisors favoring a tunnel, like the one planned for Stockton, under either Fillmore or Steiner Streets. Almost immediately, the Fillmore Street Improvement Association sprang into action with “plans for a great bore through the Pacific Avenue hill,” as the San Francisco Chronicle announced on August 9, 1911.

On January 8, 1912, James “Sunny Jim” Rolph Jr., a tunnel supporter, was sworn in as mayor of San Francisco. He in turn hired a new city engineer, Michael M. O’Shaughnessy, who eventually served 20 years in that role. Tunnels continued to dominate the mayoral agenda.

The well-organized Fillmore Street Improvement Association, promoters of the street as a business district, had the manpower and connections to pursue the tunnel idea.

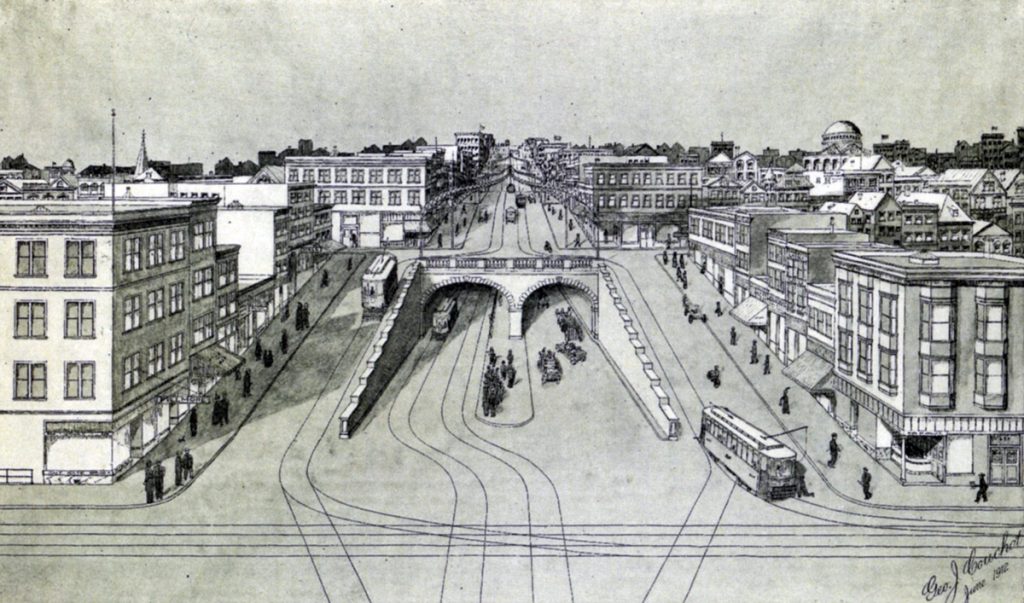

Mayor Rolph’s tunnel man, Bion Arnold, recommended the Fillmore Street Tunnel as an essential transportation link to the exposition site. He agreed on a route through the hill down Fillmore, from Sutter to Filbert Streets. His final report on the tunnel noted that it would “undoubtedly facilitate bulk passenger movements to the maximum extent” and, after the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE) closed, would be the “only available low-level route to Harbor View,”

known today as the Marina District.

Almost immediately after delivering its petition and receiving a blessing from Arnold, the Fillmore Street Improvement Association began campaigning hard. It employed an engineer and sent a committee to Los Angeles, which was well into a tunnel frenzy of its own. The men returned with a recommendation for a twin-bore tunnel through the Fillmore Street hill: one for rail and the other for vehicles and pedestrians.

“Proud as we are of Fillmore Street, it is today a cul-de-sac with a wall at each end,” said a supporting brochure. “No district can have anything but limited growth unless its main artery of traffic leads from somewhere to somewhere.”

Support for the Fillmore Street Tunnel rolled in from the Golden Gate Valley Improvement Club, the McAllister Street Improvement Club and the East of Fillmore Street Improvement Association.

The Tunnel Committee of the Civic League of Improvement Clubs also joined the bandwagon. It pointed out that the Fillmore Street Tunnel would be “the connecting link between Harbor View, the site of PPIE of 1915, and 80 percent of San Francisco’s permanent population.” The League urged speed in building the tunnel as the opening date loomed.

Yet San Francisco dragged her feet.

Meanwhile, construction had begun in 1912 on the PPIE fairgrounds and the Stockton Street Tunnel. That tunnel would be only 911 feet long, but 50 feet wide, and when completed would be the widest tunnel in the United States, able to accommodate streetcars, vehicles and pedestrians.

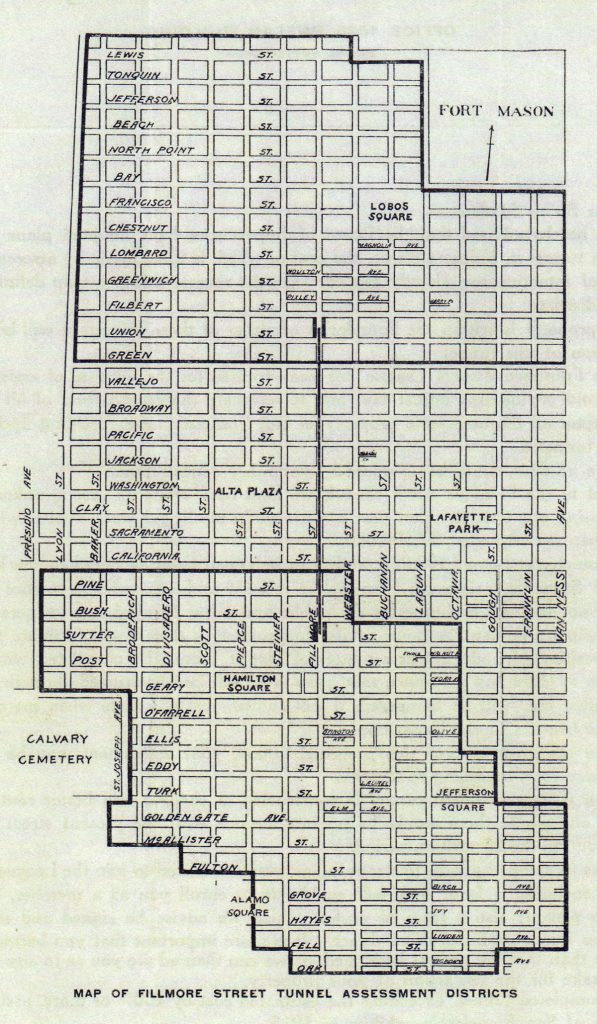

Attention turned next to financing the proposed Fillmore Street Tunnel. The city engineer’s office estimated the cost to be $2,914,002 — or “no more than $3 million,” according to Michael O’Shaughnessy. In a letter from the Fillmore Street Improvement Association to the Tunnel Committee of the Board of Supervisors, the organization reported it had received supporting signatures from 60 property owners, representing 97 percent of those holding deeds to Fillmore Street property between Sutter and Fulton, which was characterized as “the valuable business section.” Importantly, these supporters would also be the ones assessed to defray tunnel costs.

The property owners on the other side of the hill — the Harbor View side — were another matter. Herbert and Hartland Law, who owned 12 blocks, resisted at first, but came around to supporting the tunnel. However, the majority of the land in what is now the Marina Boulevard area had been purchased in the 19th century as water lots by James G. Fair, one of the so-called Silver Kings or the Irish Big Four. His two daughters, Theresa “Tessie” Oelrichs and Virginia “Birdie” Vanderbilt, inherited the property after their father’s death.

Oelrichs, who was a reigning dowager of Newport, R.I. and plagued by mental instability, held seven blocks in the Harbor View area; her sister, divorced and living in New York City, owned 22 blocks. The sisters had made separate lease arrangements with the PPIE. Oelrichs had offered her land rent-free, but with a contingency that all future taxes or assessments be paid by the exposition. Vanderbilt initially refused to lease her land at all, then relented enough to propose a lease at $60,000 per block. The PPIE committee replied that it could only pay $35,000 to $40,000 per block.

California Gov. Hiram W. Johnson came to the rescue, approving an amendment to the eminent domain law that would allow the PPIE to condemn property for exposition use. Vanderbilt was made aware of this new legislation and, after consulting her lawyers, agreed to the lower price. The lease, signed on January 13, 1912, contained a clause requiring that the PPIE pay any additional costs that might arise.

So when the Fillmore Street Improvement Association sent two members to New York City in April 1912 to ask Vanderbilt to comply with the idea of paying assessments on her property for the tunnel, they were met with resistance. Despite letters of introduction from Mayor Rolph, Archbishop Patrick Riordan, publisher William Randolph Hearst and New York Mayor William Gaynor, Vanderbilt refused to meet with the representatives. When her lawyers finally agreed to see them, the San Franciscans were told that the lease pertained; any extra costs would have to be borne by the PPIE.

The PPIE committee dealing with financial matters could not recommend any payment for tunnel assessment. In fact, it declared that the Fillmore Tunnel was not necessary for the PPIE — that other transportation methods were more satisfactory and less costly.

In April 1912, the leading light of the Fillmore Street Improvement Association, vice chairman Samuel Adelstein, declared: “If the tunnel is not built now under the present administration, it probably never will be constructed.” He pointed out that the tunnel would principally benefit Vanderbilt’s property in the future, and proposed that the PPIE pay 40 percent of the tunnel assessment, with Vanderbilt paying 60 percent. The PPIE reiterated that it would not pay any assessments at all for construction costs deemed unnecessary for the fair itself.

The Fillmore Street Improvement Association created a tunnel booklet, touting the successful Los Angeles tunnels (four completed, one near completion, five more ordered by the city council) and pointing out the increased real estate values they produced.

On April 23, 1912, the Fillmore Tunnel resolution was adopted by the city and the Board of Public Works was ordered to furnish preliminary plans and surveys. It was to be 4,332 feet from Sutter to Filbert Streets with an easy grade of 2 percent and would accommodate street cars, vehicles and pedestrians. An assessment district was unanimously approved by the Board of Supervisors. A total of 32.4 million square feet would be included in the assessment district. The PPIE voiced opposition, but was overruled.

On June 27, 1912, the San Francisco Chronicle announced that a 30-foot strip of land on each side of Fillmore Street between Filbert and Union and between Bush and Sutter would be purchased as part of the tunnel’s total cost.

Gradually, opposition to the Fillmore Street Tunnel plan began to develop from more than just the PPIE. The Divisadero Street Improvement Association urged the mayor and Board of Supervisors to exclude all land west of Pierce Street from the assessment district on the grounds that it was about to petition for its own tunnel. A new organization, the West of Fillmore Street Improvement Association, formed to protest against the Fillmore Street Tunnel. The San Francisco Tunnel League opposed it on the grounds of excessive assessments.

On the other side of the issue, Samuel Adelstein of the Fillmore Street Improvement Association became secretary-treasurer of a new organization called the Fillmore Street Tunnel Property Owners’ Association. That group published letters from pro-tunnel landowners on both sides of the Fillmore hill and as far away as the Mission, the Richmond and North Beach and urged that construction start at once.

Toward the end of 1912, a city election for charter amendments pertaining to tunnels was overwhelmingly supported by residents in the Western Addition and Harbor View districts. The Fillmore Street Improvement Association presented a resolution endorsing a bond issue for municipal railroad extensions related to the Fillmore Street Tunnel.

But by April 1913, city engineer O’Shaughnessy, a proponent of the tunnel, sounded a note of caution. If construction did not start promptly, he said, it would not be possible to complete it before the PPIE opening, scheduled for February 1915. But debates on the size of the assessment district as well as the assessment rate itself persisted.

And then it all began falling apart.

In September 1913, Adelstein became outraged when he received his own personal assessment for the Fillmore Street Tunnel based on his ownership of property on Fillmore Street between Post and Geary. His rate was 40 cents per square foot, for a total of $2,309.50. Property on the north side of the Fillmore Hill, which Adelstein believed would benefit much more from the tunnel than that on the south side, was assessed at a rate of between 7 cents and 12 3/4 cents per square foot.

Overnight, Adelstein went from leader of the pro-tunnel advocates to chief opponent. His colleagues on the Tunnel Committee of the Fillmore Street Improvement Association tried to expel him from the organization.

On September 13, 1913, the San Francisco Chronicle headlined the downward course: “Fillmore Tunnel May Not Be Built.” The Tunnel Committee recommended to the Board of Supervisors a resolution to the effect that there be an “indefinite postponement” of the Fillmore Tunnel project.

Within days, the full Board of Supervisors approved the resolution. Adelstein was blamed for this turnaround, although the supervisors claimed they had rejected the tunnel plan because of excessive property assessments and the likelihood the tunnel would not be finished in time for the 1915 exposition.

Mayor Rolph cut the ribbon on the Stockton Tunnel on December 29, 1914. Within hours, the new tunnel was hailed as a success. Six weeks later, the Stockton Tunnel began carrying many of the more than 18 million visitors to the PPIE. The railway built along Van Ness Avenue took fairgoers from Market Street to Harbor View. The privately owned Fillmore Street and Union Street streetcar lines brought patrons to the gates of the exposition.

Like the Stockton Tunnel, the Panama-Pacific International Exposition was declared a triumph. At its end, after all buildings except the Palace of Fine Arts were razed as planned, development began in Harbor View, renamed the Marina.

And the Fillmore Street Tunnel slipped into history — and oblivion.

Filed under: Neighborhood History