ART | CLAIRE CARLEVARO

Twenty-five years ago, I saw a piece of artwork by Agelio Batle at the Hayes Valley gallery owned by the visionary Federico de Vera. I bought the wall sculpture, then went in search of the artist.

Thus began my journey with a man whose creativity is born in spirituality and nurtured by skill: a true seeker, an explorer and a remarkable inspiration. Nature and the human figure are his inspirations. He delights in discovering the potential of unused materials, often castoffs: found photos, plastic milk cartons, discarded reference books.

In addition to his steady creation of unique works, Batle has invented a form of graphite artistry available in many museums and shops, including Hi Ho Silver at 1904 Fillmore Street.

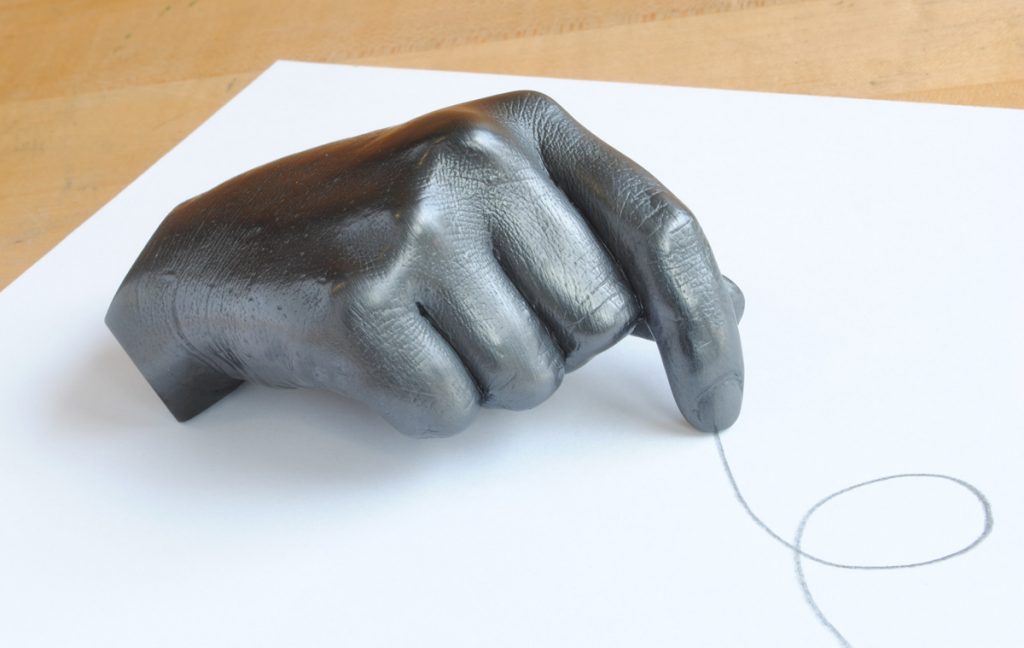

As he began experimenting with graphite in the late 1990s, Batle posed a query: “What if I were to cast a life-size version of my fist? Then a pencil could mimic a hand, and a hand could act as a pencil.”

His idea was to transform a conceptual art project into a design that could be replicated and shared. With it, he launched a successful cottage industry and a multi-generational family business. In his San Francisco studio sprouted more artistic shoots: a graphite feather, a bird skull, a cicada, an alligator, a ginkgo, an octopus, a nautilus, a lady slipper orchid — even a pea pod.

“When I work with graphite, I can’t get it out of my head that the material is from the dead,” says Batle. “This non-precious, lustrous mineral is the exhumed remains of plants and animals that perished a million years ago. A bit more pressure and it could have been diamonds — an irony in and of itself.”

Among those involved in creating Batle’s art are his wife Delia and his sons Noa and Nilo.

“From a very young age, my father told me: Anything worth doing is worth doing differently,” says Nilo Batle, now a film student at the California Institute of the Arts. “At the time, I did not fully understand what he meant and only applied the philosophy to artistic pursuits. As I grow older, I try to apply this philosophy to all aspects of my life.”

Batle’s friend, the writer and teacher Jim LeCuyer, remembers him striving to combine a background in chemistry with his creative talents while developing the graphite compound used in his practical sculptures. The artistically formed pencils charmed buyers at craft shows, and soon Batle and his family had established a network of sellers around the world.

“It’s quite an achievement,” says LeCuyer. “Agelio is proof that intelligent thought creatively applied can not only make a fine life for one person, but for all around him.”

That includes his brother Gil Batle, now working as an artist after a troubled past that included multiple terms in prison.

“Agelio saved my life. Today I’m clean and sober and actually making a decent living with my art and I owe it all to Agelio,” says his brother. “He would hire me and house me, again and again and again. At times it was difficult and frustrating for me to express myself on this art path, but later it became clear when he told me: You can’t just make art, Gil, you have to live it.”

Claire Carlevaro, for many years the owner-director of the Art Exchange Gallery in San Francisco, is the author of the recently published book The Art of Agelio Batle.

Filed under: Art & Design