ARCHITECTURE | BRIDGET MALEY

“For some 14 months now the normally placid Pacific Heights intersection of Washington and Maple Street has been host to what might be described as a perpetual traffic jam,” reported a Chronicle article on June 17, 1951, headlined “A King-Size House That Floats on Stilts: Mendelsohn Creates a Landmark.”

Architect Erich Mendelsohn, a German modernist whose innovative designs had riveted the Weimar Republic in the 1920s, had indeed produced one of San Francisco’s most innovative — and attention-getting — modern homes.

Mendelsohn, a Jewish Berliner, came to San Francisco in 1945, via England, Israel and New York, after fleeing Germany in 1933 to escape the ascent of Adolph Hitler. Mendelsohn carried out only two commissions in San Francisco: the 1946 Maimonides Hospital at Sutter and Divisadero, and his house for Leon and Madeline Russell, completed five years later. When Mendelsohn died in San Francisco in 1953, his Chronicle obituary reported: “Ranked with France’s Le Corbusier and America’s Frank Lloyd Wright, Mr. Mendelsohn devoted his professional career to scraping the gingerbread off buildings of the 19th century and designing structures for 20th century living.”

His career was launched in 1919 when he was commissioned to design the Albert Einstein Astrophysical Observatory in Potsdam. An expressionist landmark, the Einstein Tower, as it became known, housed a solar telescope. Mendelsohn’s other significant projects across Germany, Israel and the United States included synagogues, department stores, factories and hospitals — all executed in a purely innovate approach to urbanism, usually in concrete with a sinuous curve, now regarded as masterpieces of streamlined modernism.

The Washington Street home was built for notable occupants. Levi’s heir Madeline Haas married Leon B. Russell, an aspiring screenwriter, on March 9, 1946, in the grand Victorian Franklin Street home of her aunt and uncle, Samuel and Alice Haas Lilienthal. Her parents, Charles and Fannie Stern Haas, had both died before she was a teenager. Madeline Haas Russell was a great-grandniece of Levi Strauss, and became one of the renowned San Francisco philanthropists of her era.

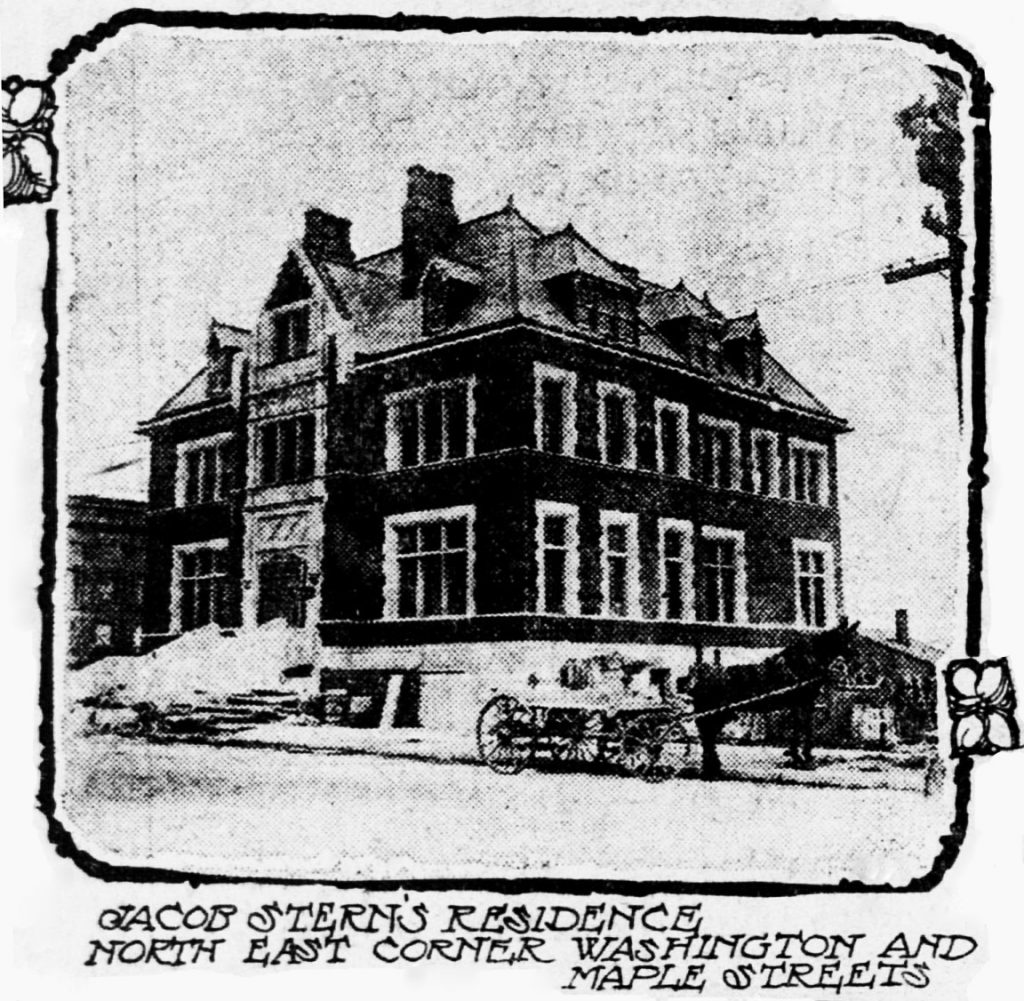

Russell inherited the lot at the northeast corner of Washington and Walnut Streets, perched above the Presidio. Her grandfather, Jacob Stern, had built a house on the large parcel in 1910. The Stern house, in which Madeline spent many days, was brick with white stone trimmings carved in Gothic cathedral style. It reportedly contained 25 rooms and a staircase and hall two stories high. As construction began on Mendelsohn’s house for the Russells, both the demolition of the Stern mansion and the completely Modern aesthetic of its replacement must have come as a shock to the locals.

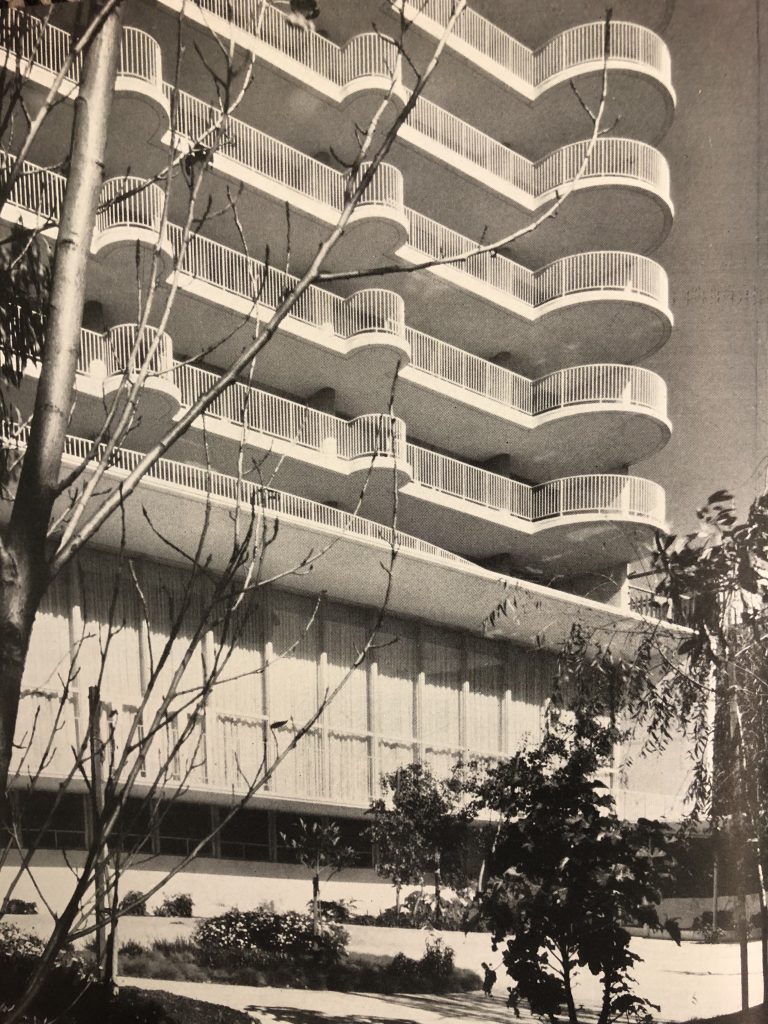

Taking advantage of a steeply sloping lot, the Russell House is L-shaped, with two wings framing a large courtyard. The main wing is raised and supported on slender steel columns, or piloti. The courtyard continues under the elevated main wing, affording magnificent views of the Presidio out to the bay. The dynamic cylindrical master bedroom bay window appears to float above a tree canopy at the northwest corner. Today the house is shrouded in landscaping, furthering its elevated appearance. In a nod to his Bay Area contemporaries, the Russell house is sheathed in horizontal redwood siding, unlike much of Mendelsohn’s other work, which was executed in concrete.

The Russell House has many distinctive elements that reflect Mendelsohn’s earlier work in Germany and Palestine. It also shares a number of features with his other San Francisco project, the Maimonides Hospital, located on Sutter Street near Divisadero, but now altered and encased in other medical buildings. These commonalities included horizontal expanses of ribbon windows, forms raised off the ground on slender piloti and circular elements, such as porthole windows and curved balconies or bays.

Mendelsohn often used a curvilinear form. The curved balcony, used in both of his San Francisco projects, showed up in early works in Germany, especially housing projects. Paul Goldberger, the former New York Times architectural critic, once observed that Mendelsohn’s final commission, the Russell House, had “beloved curves, coming back at the very end, breaking free to soar over the bay and the Golden Gate.”

Madeline and Leon Russell had three children, but divorced in 1957. Madeline never remarried. She continued to live in the house until her death in 1999.

Filed under: Bridget Maley, Home & Garden, Landmarks