By BRIDGET MALEY

Sometimes mistaken for an Episcopalian church, St. John’s Presbyterian, the eclectic Shingle Style landmark at the corner of Lake Street and Arguello Boulevard, does indeed have its architectural roots in the Episcopal building tradition. And it has a rich history.

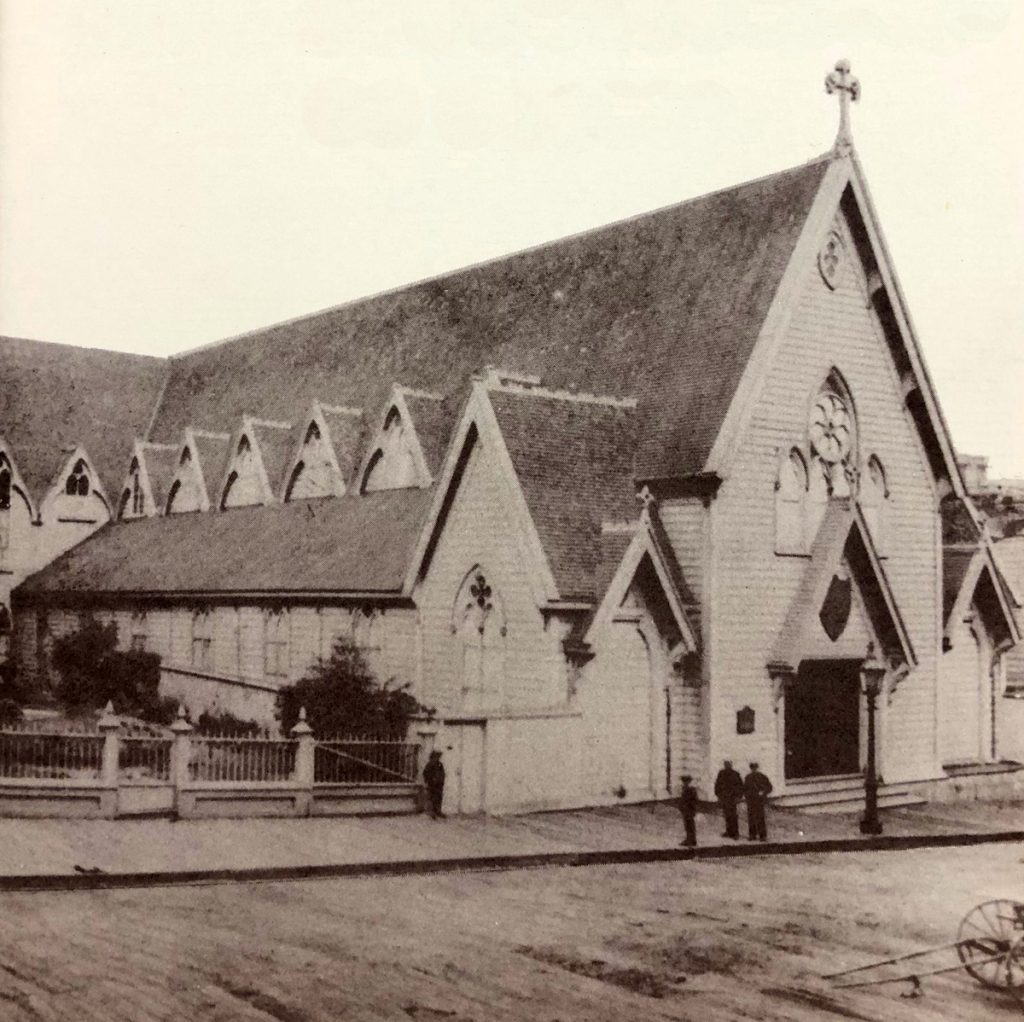

The story begins in March 1870, when a newly established Presbyterian assembly acquired a building on Post Street between Mason and Taylor: the former St. James Episcopal Church, built in 1867. Not much is known of this earlier building, and no architect has been linked to its design. Historic images depict a small, wooden frame structure with a swirl of English country church, Tutor Revival and American Carpenter Gothic influences. It had an almost rural character, sharing a lot with a residence and small yard in what was an increasingly urban San Francisco.

The Episcopalian priest who was the rector of St. James apparently defected to the Catholic church in 1870, leaving the building available for another congregation.

St. John’s first minister was the Rev. Dr. William Anderson Scott, a controversial figure both loved and reviled among San Francisco’s early religious leaders. Scott disembarked from an arduous New Orleans journey to a somewhat lawless, chaotic — some would say “godless” — San Francisco in 1854. His booming sermons soon found followers, and later Scott would help form Calvary Presbyterian Church, now at Fillmore and Jackson, which is celebrating its 165th anniversary this month on July 21.

A few years after he arrived in San Francisco, Scott challenged the city to eradicate the Committee of Vigilance, a citizens’ group ostensibly formed to tamp down the growing crime problem among the population that flocked here during the Gold Rush. His work resulted in Scott’s hanging in effigy. Later, during the Civil War, Scott, who was raised in the South, offered prayers for both President Abraham Lincoln and Confederate “President” Jefferson Davis. Outraged by this gesture to the southern cause, San Franciscans again hanged Scott in effigy, and some threats of lynching were reported.

Scott and his family quietly left town. However, San Francisco would call to him again and Scott returned in the late 1860s.

It was under his leadership that the St. John’s congregation was founded and that it acquired the former Episcopal church on Post Street. Henry Mayo Newhall, a prominent San Francisco auctioneer and investor — as well as a Scott supporter — likely assisted with its purchase.

In 1876, Scott’s daughter, Louisiana, married Arthur W. Foster, a railroad man, land speculator and later a regent of the University of California. Foster became a major benefactor of St. John’s and the San Francisco Theological Seminary, which Scott had founded in 1877. When Scott died in 1885, his obituary commented that he was “known for his charity, but also for his learning.” Several years later, Scott’s son-in-law donated land in San Anselmo for a permanent seminary site, and the seminary’s initial library was formed from Scott’s extensive personal collection.

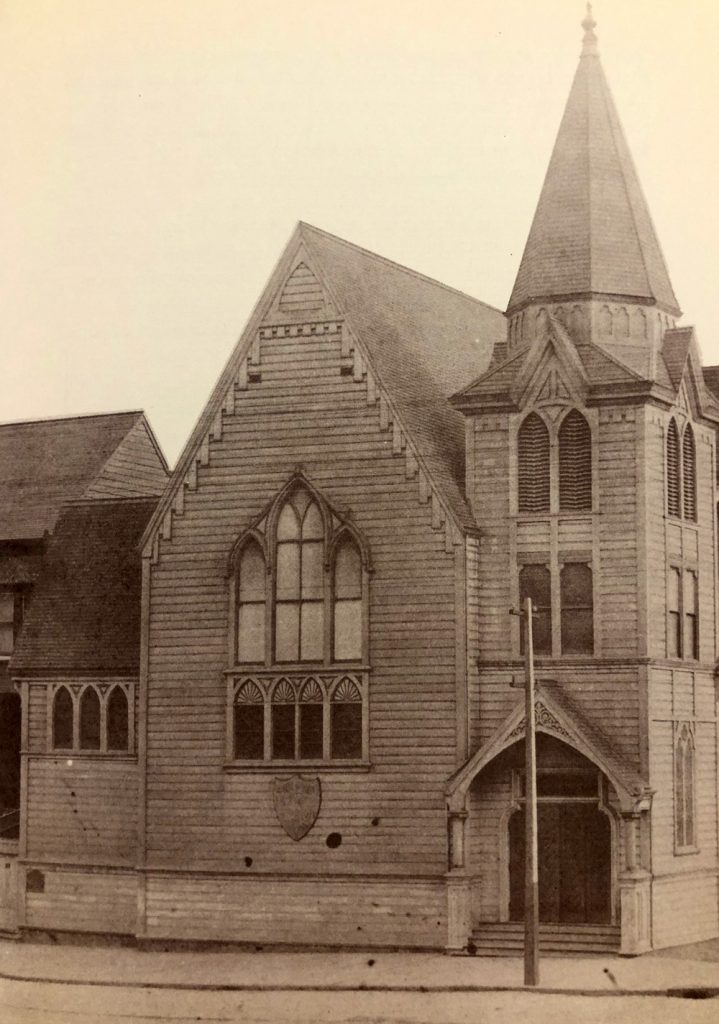

In 1888, the St. John’s congregation decided to erect a larger and more imposing edifice in a new location. On March 15, 1888, the Chronicle reported that a site at the corner of California and Octavia Streets had been acquired. It noted that, at the time, the congregation owned the “largest organ in the city and it will be placed in the new church.”

Designed by architect Clinton Day, St. John’s second church building was designed to accommodate “very handsome memorial windows to the founders of the church.” A sketch conveyed the congregation’s continued fondness for Gothic-inspired architecture. The building, with a steeply pitched gable and tall tower, had several windows accommodating Gothic arches.

Historic photographs confirm that the second St. John’s continued the Episcopalian architectural tradition of the first. Day’s design also incorporated several interior elements from the earlier building, including some furnishings, the choir screen, pews and the chancel arch, inscribed: “Worthy is the Lamb that was slain to receive honor, glory and blessing.”

The congregation remained on California Street for fewer than 20 years, when another move, even farther west of downtown, was contemplated.

The third St. John’s — the one still standing at Lake and Arguello — was designed by architects Dolliver and Dodge in 1905, and embraced the regional version of the Shingle Style that became known as the First Bay Tradition. Though not usually identified with the regional tradition, these two architects were well trained and would have been familiar with the rustic, heavily shingled houses of Bernard Maybeck, Ernest Coxhead, Albert Farr, A. C. Schweinfurth and Julia Morgan that were cropping up in Pacific Heights and Presidio Heights during the period. Coxhead’s extensive work for the Episcopal Church during the era also resulted in other small-scale shingled edifices in San Francisco such as St. Mary the Virgin in Cow Hollow and the Chapel of the Holy Innocents in the Mission.

John Walter Dolliver (1868-1927) was a native San Franciscan who attended architecture school in Germany before jaunts to both Boston and New York. He returned to San Francisco in 1900. George Andrew Dodge (1866-1919) was born in California, but little is known about his training. Dodge was well connected; his 1892 marriage to Maude Bennett took place in the Alameda home of prolific house developer Joseph A. Leonard, for whom Dodge worked at the time. The partnership of Dolliver and Dodge began in 1902, but was short-lived, with the two separating before the 1906 earthquake.

Tasked with repurposing some interior and exterior architectural features and stained glass windows from Day’s 1888 building, Dolliver and Dodge crafted a Shingle Style gem to accommodate the congregation’s architectural treasures.

The building’s stunning art glass window facing Arguello Street is a memorial window to benefactor Arthur Foster. The window is the work of William Schroeder, of California Art Glass works, whose studio was described as fulfilling important commissions for both private houses and public buildings.

An article in Architect & Engineer in June 1908 identified the window as one of the largest pieces of art glass in the state, describing its scene as “ravens feeding Elijah, who is seated by a brook, the waters of which seem to be running and dancing when the light shines through the window. The perspective in this scene is as perfect as a painting.”

Filed under: Bridget Maley, Landmarks