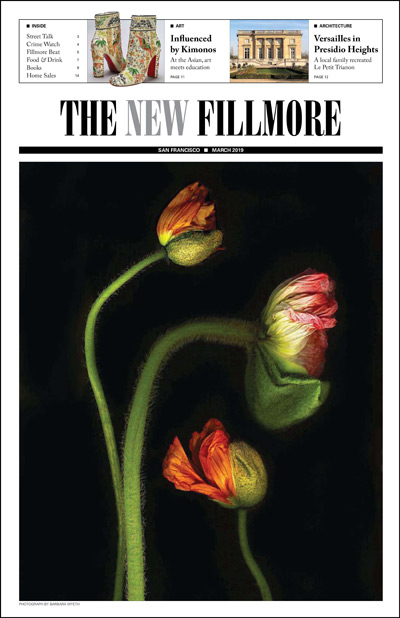

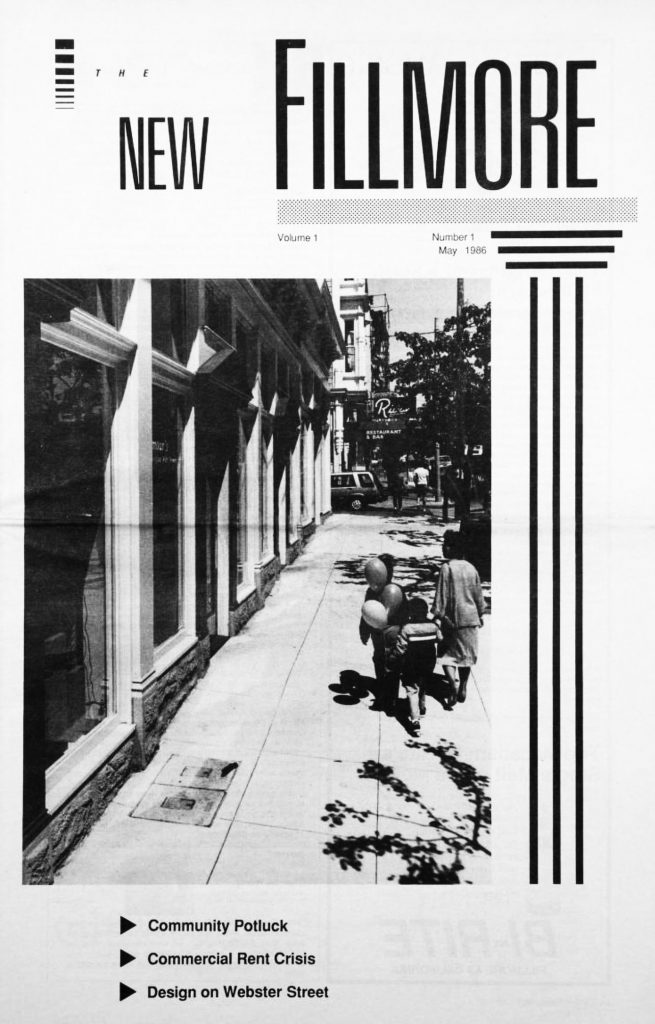

FROM VOL. 1, NO. 1, in June 1986 until her death in 1999, historian and preservationist Anne Bloomfield, a neighborhood resident, wrote a column every month for the New Fillmore called “Great Old Houses.” Many of her columns were collected into the 2007 book, Gables & Fables: A Portrait of San Francisco’s Pacific Heights, with amendations by her husband, music critic Arthur Bloomfield.

One of the people touched by her work was Bridget Maley, an architectural historian then working with the respected Architectural Resources Group in San Francisco. Maley, a neighborhood resident, now has her own firm, architecture + history. With this issue, she takes up the mantle and begins a regular column on the historic architecture and places in the neighborhood, picking up where Anne Bloomfield left off.

So you knew Anne Bloomfield?

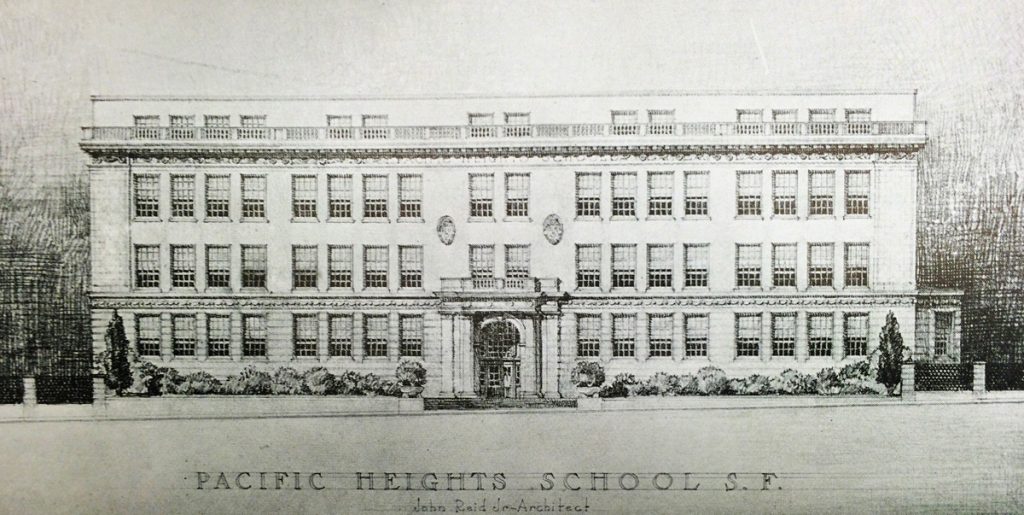

I had the pleasure of getting to know Anne through several projects and mutual membership in a few organizations. She left an indelible mark on San Francisco. Anne was responsible for many individual landmarks and historic districts. These sites would never have been designated and protected without her tenacity and resolve. That includes her beloved Webster Street Historic District, which she meticulously studied and documented.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in Richmond, Virginia, and attended Salem College, a small women’s college in North Carolina with a strong history and many historic buildings. It’s like a mini Williamsburg. I became interested in historic preservation through internships and archaeology at Old Salem. Then I worked at Monticello and Thomas Jefferson’s octagonal retreat house, Poplar Forest, and then was accepted into the architectural history program at the University of Virginia. It’s in the School of Architecture, so you interact with architects, landscape architects and urban planners. It’s a phenomenal program.

What brought you to San Francisco?

I met my husband at UVA. He had gone to college at Berkeley and wanted to come back. I did not protest.

Tell us about your day job.

I’ve worked on some of the city’s most significant structures, including the Conservatory of Flowers and the Old Mint, and helped make the Swedenborgian Church a National Historic Landmark. I’ve also had projects across the west in the Grand Canyon, in Hawaii — and I even got to go to Alaska to look at Coast Guard stations. I’ve researched modern buildings in Palm Springs and the incredible collection of early skyscrapers clad in terra cotta in downtown Los Angeles.

Favorite local buildings and architects?

Oh, there are many. Julia Morgan, for so many reasons, but mostly because she was so smart and talented, yet incredibly modest. A. C. Schweinfurth, who designed the Swedenborgian Church, because I just like to say Schweinfurth. Arthur Brown Jr., who designed City Hall, partly because my great friend Jeff Tilman wrote so eloquently about him. The first sentence of his book is: “Arthur Brown Jr.’s story begins with the transcontinental railroad and ends with the atomic bomb.” Wow! I also love the whimsical work of Ernest Coxhead.

What can we expect in the coming months?

I’ll focus both on the houses in the neighborhood and the people who lived in them. I loved that about Anne’s articles. She found such juicy stories. I also love our parks on this side of the city and will try to tell their stories, as well as those of some treasured homes Anne didn’t get a chance to talk about. Maybe we’ll also delve a bit into the neighborhood’s more modern buildings, such as some of William Wurster’s houses, or a few commercial and institutional buildings.

Filed under: Bridget Maley, Landmarks, Neighborhood History | Leave a Comment »