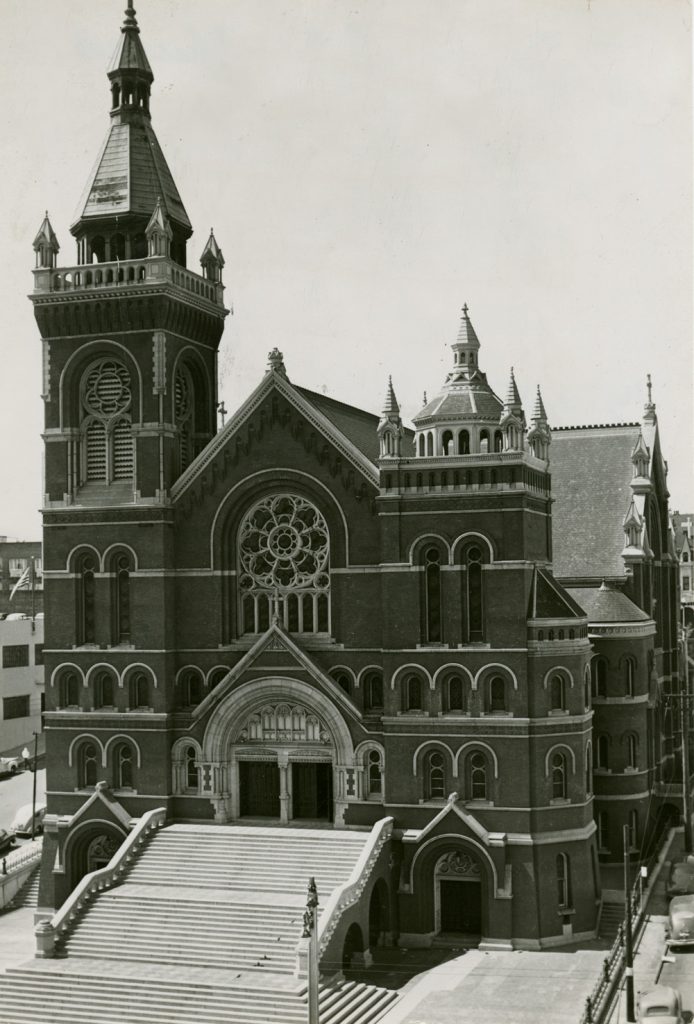

St. Mary’s Cathedral soon after its opening, beyond the tower of St. Marks Lutheran Church. Photos: San Francisco History Center | San Francisco Public Library

LANDMARKS | BRIDGET MALEY

May 2016 marks the 45th anniversary of the dedication of the Cathedral of St. Mary of the Assumption, a recognized masterpiece of religious architecture at 1111 Gough Street. Opening after an agonizing design process, the building was not immediately loved by many of San Francisco’s Catholics, who had previously worshiped in two very traditional churches.

Just five years after the discovery of gold in California, San Francisco’s Catholic Cathedral of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception received its first worshipers. The brick edifice, located at the corner of California and Grant Streets, was reduced to a shell in the 1906 earthquake, but was triumphantly rebuilt. Catholics had already outgrown that first cathedral and, amid much pageantry, laid the cornerstone of San Francisco’s second Catholic cathedral at the corner of Van Ness Avenue and O’Farrell Street on May 2, 1887.

After four years of construction, the building was dedicated in January 1891. The Gothic Revival red brick church, with its dramatic and steeply laid front stairs and beautiful rose window, served the city’s Catholics until the early 1960s. On the evening of September 7, 1962, a major conflagration consumed it. Archbishop Joseph McGueken was quoted as saying shortly after the fire: “It is my feeling that we should rebuild on the same site … a modern, contemporary design, but not what most people call modernistic.”

By the late 1960s, the archdiocese had selected San Francisco architects John Michael Lee, Paul A. Ryan and Angus McSweeney, working in conjunction with internationally recognized architects and engineers Pier Luigi Nervi and Pietro Belluschi, to design a radically new structure. The architect selection, and other project decisions, were controversial.

Gerald Adams, writing in a lengthy Chronicle article in October 1970, recalled: “Long before the first bucket of concrete was poured in early 1968, the archbishop was picketed, the site of the cathedral was picketed, the cathedral architects were attacked as relative unknowns; the cathedral design ridiculed as an imitation of something Japanese and the project itself censured as an affront to the poor.”

It all started with a need for a larger site. The Van Ness and O’Farrell location was declared too small for a “modern” cathedral. A series of complex and sometimes tense negotiations, land trades, purchases and sheer determination on the part of the archdiocese resulted in a site bounded by Gough, Geary, Ellis and Cleary Court. Included in the deal was an agreement that KRON-TV would get the old cathedral site for construction of new offices and studios; it did, but the low-rise building is now slated to be demolished for a new residential tower.

The selection of an architect was equally difficult for the archdiocese. In what could be described as San Francisco’s most important religious commission in a generation, many of the most influential architects in California — and throughout the world — were rumored to be interested, including John Carl Warnecke, Gardner Daily, Mario Ciampi, Louis Kahn and Marcel Breuer. Gerald Adams in his Chronicle article summarized the process: “When on April 8, 1963, the archdiocesan office announced that the architects would be a joint venture team of Angus McSweeney, Paul Ryan and John Lee, the reaction was a stunned, ‘Who?’ ”

Architectural critic Allen Temko was so incensed that he wrote of McSweeney: “One cannot possibly associate his name with a single significant piece of modern architecture.” The situation was further complicated when the editor of Worship, a magazine that promoted liturgical reform and modern design in church architecture, noted of a preliminary design: “It reminds me of the effort of a camel and a donkey to mate.”

A different solution became a priority. Belluschi and Nervi were asked to become part of the team.

Four times larger than the building it replaced, and on a new site, the revised design proposed to occupy a key location within the Western Addition being masterminded by the Redevelopment Agency.

It included not only the church, but also a rectory, the archbishop’s residence, an event center, underground parking and a landscaped plaza. The final designs were highly reminiscent of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Tokyo, completed earlier in the decade by Kenzo Tange. Indeed, Nervi and Belluschi were accused of plagiarizing Tange’s innovative use of concrete shaped into a hyperbolic paraboloid. Nonetheless, the design was a huge improvement over the early renditions and Nervi and Belluschi elevated the skills and creative mixture of the design team.

Belluschi was an Italian-born designer who had studied in Rome and then immigrated to Portland, Oregon, and joined a small architectural practice. He served as dean of the architecture school at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1951 to 1965. His significant works include the Equitable Building in Portland (1948), the Pan Am Building in New York City with Walter Gropius (1963), 555 California in San Francisco as a consultant to Wurster, Benardi and Emmons and Skidmore Owings and Merrill (1969), the University of Virginia School of Architecture (1970) and many churches throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Pier Luigi Nervi was an Italian who became widely known for his innovative use of reinforced concrete and Belluschi suggested him for the St. Mary’s project. Nervi believed architecture and engineering were interconnected and that knowledge of materials, nature and construction were essential to designing innovative buildings. In his work, Nervi made reinforced concrete his material of choice — with key commissions in this idiom including the UNESCO Headquarters in Paris (1950), the Fiat Factory in Turin (1955) and the Olympic Stadium in Rome (1960).

Using a structural scheme involving a simple cube soaring upward to a vertical hyperbolic paraboloid, St. Mary’s exterior is sheathed in a pale Italian travertine. The lower horizontal cross section of the roof forms a square and the top intersecting paraboloids emulate a cross. The structure is crowned by a 55-foot gold cross. The exquisite exterior bronze thorn-like entry doors and the bronze bas-relief above, designed by Enrico Manfrini, evoke the crucifixion. People of all races and faiths are represented as one family in Manfrini’s metal relief abstraction.

The red brick floor in the interior recalls earlier California Mission churches. Throughout the building, clear glass windows afford spectacular views of the surrounding city. A reflection of new liturgical regulations that came out of the Second Vatican Council, the altar is central. Artist Richard Lippold’s baldacchino has been described as “angels dropping stars.” The pews are arranged so that no congregant sits more than 75 feet from the altar. Behind it, a panel of colored glass accompanies the tall, narrow windows that form the intersections of the hyperbolic paraboloids.

Filed under: Bridget Maley, Landmarks