ART | JEROME TARSHIS

During the early and middle ’60s, when I was thinking about moving from New York to San Francisco, one of the inducements was that Bruce Conner lived here. My avant-garde film friends thought his first film, A Movie (1958), was an instant classic, followed by one success after another.

The objects he made — assemblage sculptures — were being shown at major galleries in New York, London, Paris, Rome and Mexico City. He was in great collections on both sides of the Atlantic. Not bad for a 30ish artist born and brought up in Kansas.

A more complicated Bruce Conner is the subject of “It’s All True,” his fullest retrospective so far, almost worshipfully received earlier this year at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and now at SFMOMA through January 22.

In 1965, Conner wrote to his poet friend Michael McClure that he had “a feeling of death from the ‘recognition’ I have been receiving. I feel like I am being catalogued and filed away.”

Unlike New York, San Francisco offered him an art scene in which very little avant-garde work by serious artists was sold. The artists could complain they were being ignored and, at more or less the same time, feel relieved they were outside what Conner referred to as “the art bizness.”

Always striving to avoid categorization, Conner produced work in a dizzying variety of media, ranging from the films and assemblages that are his most obvious contributions to art history to photograms made by silhouetting his body against photo-sensitive paper.

“I was feeling very nebulous about my own identity, and uncertain how to cope with that,” he later explained. “The main thing that I could understand was that I had a body that I could never get out of.”

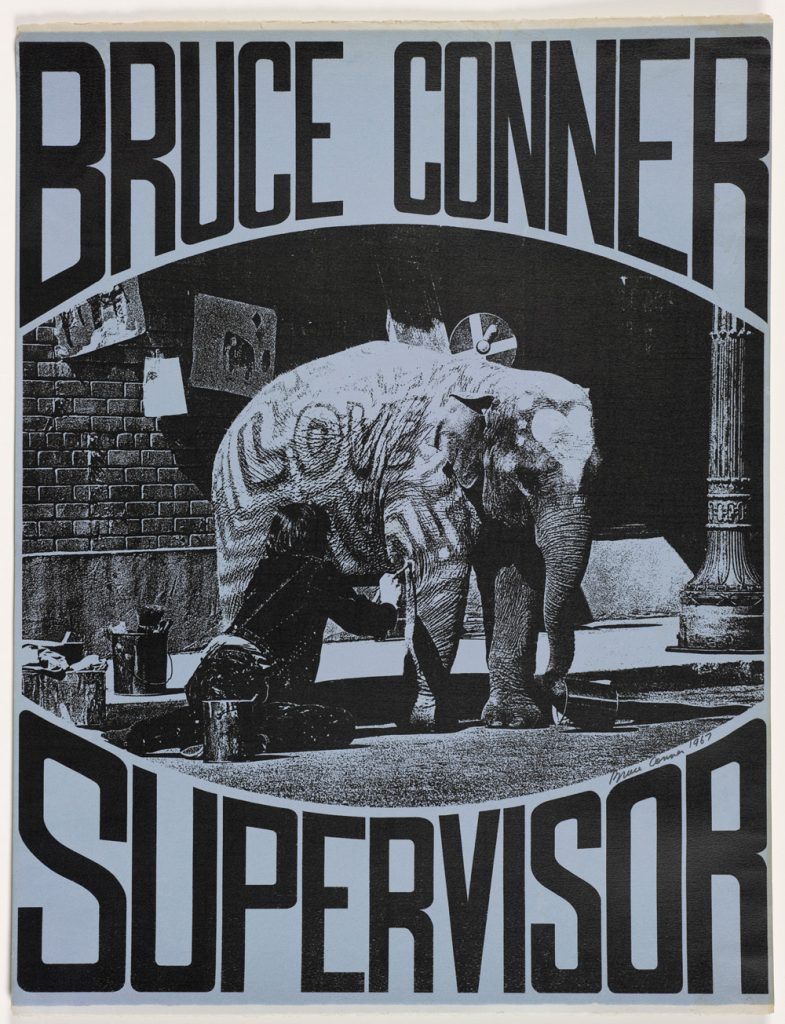

San Francisco’s public world offered him greater opportunities to get out of himself. In 1967, he ran for the Board of Supervisors (and got 5,375 votes). One of his campaign posters was illustrated with a picture of an elephant; another showed Conner in a sailor suit at the age of 2 1/2.

In the printed voter’s guide, each candidate listed an occupation. Though some were conventional — “Incumbent” or “Attorney” — others were less so; a Trotskyist might be labeled as “Socialist Worker.” Conner listed himself as “Nothing.”

The story of one of his assemblages, Child (1959), points up the ironies of Bruce Conner’s early success. It was a black wax effigy of a child, tied to a battered high chair with nylon stockings. In Conner’s mind, the effigy originally stood for Caryl Chessman, who was awaiting execution. The message expanded to a general outcry against violence perpetrated by individuals or governments, and against the repression of any childlike affirmation of life.

Exhibited at the de Young Museum, Child got national publicity. Local moralists found it outrageous: “He must hate children!” Up in the stratosphere, no problem: Conner sold the piece to Philip Johnson, the ultra-Establishment architect and collector, who later gave it to the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The Philip Johnson narrative was part of the truth. Conner’s revulsion against the consumer society and the art world was another part of the truth. The SFMOMA exhibition memorializes an artist whose talents — not least a talent for self-promotion — walked hand in hand with an outstanding ability to summon up discomfort. San Francisco helped take the edge off.

Fillmore Street had a lot to offer Bruce Conner. The building at 2322 Fillmore, called “Painterland” by Conner’s high school friend Michael McClure, who lived in the building with his wife, Joanna, was Conner’s first home in San Francisco. Over the longer term, the building offered Conner associations with artists who shared his hostility toward the art world’s idea of success. Among his several unwilling-to-be-categorized neighbors were the distinguished artists Joan Brown and Jay De Feo.

Conner and Jean Sandstedt, herself a gifted artist, married in her native Nebraska in September 1957 and set out for San Francisco. They lived with the McClures on Fillmore for a few weeks and then moved into an apartment around the corner on Jackson Street.

Down the hill was an African-American community being redeveloped out of its former existence. It offered Bruce Conner not only jazz — music of all kinds lay at the center of many of his films — but discarded fragments of a consumer society. There were unwanted bits and pieces lying in the street for the taking, or available at low prices in the neighborhood’s thrift shops.

Fillmore Street also offered him exhibition spaces. He had his first one-person show in San Francisco at the East-West Gallery, at 3106 Fillmore, and significant later shows around the corner at the Spatsa Gallery, at 2192 Filbert, and at the Batman Gallery, at 2222 Fillmore.

One of his sadder art-world misunderstandings arose from his affection for the neighborhood. He and a number of other Northern California artists were included in “The Art of Assemblage” in 1961, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, one of the great exhibitions of its time. In 1960 its curator, William Seitz, came out to San Francisco to have a look at a promising new art scene.

Conner took Seitz to artists’ studios, but also to black neighborhoods and especially to a second-hand shop on McAllister Street whose owner also made assemblage sculptures. He hoped Seitz would fall in with his heartfelt assertion that collage and assemblage had their origin in folk art, and not least in black folk art.

The resulting catalogue essay made no mention of McAllister Street; it pointed to Picasso and Braque as precursors of the young artists represented in the show. Conner was incandescently angry.

He was eager to tell the world that, successful as he was, admired in New York before he was 30, sophisticated as his art seemed to be, his work had artistic roots in the Harlem of the West.

As the title of the retrospective tells us: It was all true.

Filed under: Art & Design, Locals, Neighborhood History